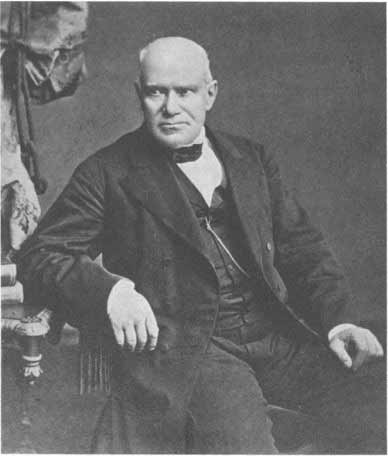

Adolf

Anderssen was born in Breslau, Germany (what is now Wroclaw, Poland)

on July 6, 1818. He lived there, unmarried, most of his quiet life,

teaching, caring for his widowed mother and unmarried sister and playing

chess. After graduating from the local Volksschule, he attended the St.

Elizabeth-gymnasium in Breslau, majoring in philosophy and mathematics.

After graduating, he took a position as mathematics instructor at the

Friedrichs-gymnasium from 1847, a position he held until 1865 when he was

promoted to professor and given an honorary doctorate degree by the town

of Breslau for his accomplishments in chess. He remained at the Friedrichs-gymnasium

until he died. Adolf

Anderssen was born in Breslau, Germany (what is now Wroclaw, Poland)

on July 6, 1818. He lived there, unmarried, most of his quiet life,

teaching, caring for his widowed mother and unmarried sister and playing

chess. After graduating from the local Volksschule, he attended the St.

Elizabeth-gymnasium in Breslau, majoring in philosophy and mathematics.

After graduating, he took a position as mathematics instructor at the

Friedrichs-gymnasium from 1847, a position he held until 1865 when he was

promoted to professor and given an honorary doctorate degree by the town

of Breslau for his accomplishments in chess. He remained at the Friedrichs-gymnasium

until he died.

Although Anderssen was nine when father taught him how to play and he

learned most of what he knew from William Lewis' 1935 book, "Fifty Games

between Labourdonnais and McDonnell", he was slow to develop his chess

talent. In fact, his original attention was focused on chess problems, an

area in which he achieved some minor success, publishing a collection of

his problems in 1842.

Breslau had an active chess society with many homegrown players as well

are celebrated visitors whom he was fortunate enough to play during his

development - players such as Harrwitz, Bledow, von der Lasa, Mayet,

Löwenthal and Hanstein. Anderssen became a contributing editor to the

Deutsche Schachzeitung in 1846 and in 1848, he drew a match against Daniel

Harrwitz, one of the strongest players in Europe. Because of the

fortuitous match, he was invited to play in the first international

tournament to be held during the London Exposition of 1851 at the St.

George Chess Club at 5 Cavendish Square, London. But Anderssen was just a

math instructor and he decided the expense of traveling was too great.

Howard Staunton, who organized the tournament and who was eager to obtain

the best players possible offered to pay the difference in Anderssen's

expenses and winnings with his own money. (the tournament committee

offered this to all non-European players with the particular hope of

getting St. Amant, who was living in California at the time, to attend).

It was a generous offer which Anderssen accepted. Staunton never had to

pay anything since Anderssen unexpectedly swept away with first place

defeating Lionel Kieseritzky, Józef Szén, Staunton, and Marmaduke Wyvill.

(The other contestants were: Lowe, H. Kennedy, E. Kennedy, Mayet,

Löwenthal, Williams, Mucklow, Newham, Brodie, Bird, and Horwitz). His

prize was Ł183 and a silver cup. But Anderssen didn't get to keep his

entire winnings since he and Józef Szén had made a private arrangement,

each agreeing to give the other a third of their winnings if either took

first prize.

After the tournament Anderssen played some casual games with Lionel

Kieseritzky, another mathematics instructor turned chess professional, at

Simpson's Divan, one of which became known as Anderssen's Immortal Game,

in which he sacrificed a bishop, both his rooks and finally his queen, to

give mate. Kieseritsky was so excited by his opponent's play that right

after the game, he hurried to telegraph the score to his chess club in

Paris. La Régence published the game in July 1851.

In another casual game the next year, 1852, played against Jean Dufresne

in Berlin, Anderssen created yet another classic which has been dubbed the

Evergreen Game after a comment by Steinitz about it being the "evergreen

in Anderssen's laurel wreath" possibly in reference to the Berliners

crowning Anderssen with a laurel wreath when he returned from London in

1851. (the following year, 1853 Dufresne won the first Berlin Tournament)

Between 1857 and 1861, Anderssen experienced some set backs. First was a

poor showing in the 1857 Manchester Tournament and then his loss of a

match against Morphy in 1858. However in 1861 he won a match against

Ignatz Kolisch, a strangely powerful, yet not well known, professional

player of that time. This match was timed using sand clocks.

His roll continued with first place at the London

Tournament of 1862 and a drawn match against Louis Paulsen that same year.

By that time, with the retirement of Morphy, Anderssen was the undisputed,

though unofficial, World Champion. In fact, Steinitz proclaimed himself

World Champion after defeating Anderssen in their match of 1866. It was a

close match, Steinitz winning eight to Anderssen's six and it was the

first time mechanical clocks had ever been used. In 1864 he became

co-editor of the Neue Berliner Schachzeitung, with Gustav Neumann.

.

Anderssen defeated Zukertort decisively in a 1868 match +8 -3 =1

followed by an August, 1869 victory at the Hamburg Chess Congress

and then a second victory at the Barmen Chess Congress scoring 100%..

Anderssen was already over 50 years old but possibly his greatest

achievement was yet to come. In 1870, he won the Baden-Baden tournament,

undoubtedly the strongest tournament ever held up to its time, beating out

Wilhelm Steinitz, as well as Gustav Neumann and Joseph Blackburne.

He took first place at Crefeld in 1871, but lost a match to Zuckertort

that same year. He took first place at Leipzig in 1876 then lost a match

to Louis Paulsen that same year. He took second place at Leipzig in

1877 at the age of fifty nine but once again that same year lost another

match to Paulsen.

Anderssen died March 13, 1879 of a heart attack. His obituary spanned

19 pages in the German chess magazine Deutsche Schachzeitung.

As much as for his chess, Anderssen is remembered for for his character.

He was loved by everyone. Reverend George MacDonnell (a talented amateur)

describes Anderssen: "He was massive in figure, with an honest voice, a

sweet smile, and a countenance as pleasing as it was expressive. I never

saw more light and sweetness from any eyes than from his."

Edge describes Anderssen: "I have never seen a nobler-hearted gentleman

than Herr Anderssen. He would sit at the board, examining the frightful

positions which Morphy had forced him, until his whole face was radiant

with admiration of his antagonist's strategy, and positively laughing

outright, he would recommence resetting the pieces for another game,

without a comment."

Steinitz wrote: "Anderssen was honest and honorable to the core.

Without fear or favor he straightforwardly gave his opinion, and his

sincere disinterestedness became so patent....that his word alone was

usually sufficient to quell disputes...for he had often given his decision

in favor of a rival..."

Adolf Anderssen's Immortal and

Evergreen Games

|