|

MR. BLACKBURNE'S GAMES at

CHESS

SELECTED, ANNOTATED AND ARRANGED HIMSELF

EDITED, WITH A BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH AND A BRIEF HISTORY

OF BLINDFOLD CHESS

P. ANDERSON GRAHAM

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

NEW YORK AND BOMBAY

1899

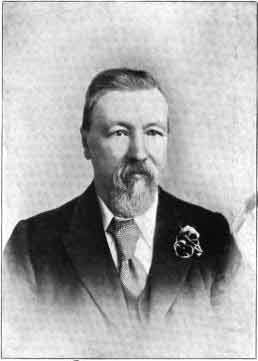

(from a photograph by J. Pettingall)

I Wish Mr. Blackburne could or would have written his

own life. No one else can so happily recall the series of mimic " battles,

sieges, fortunes," that form the history of a great chess player. In

conversation I have known few who could so vividly reproduce the tone, gesture

and accent of the dead or absent, and it would have been pleasant to let him

tell his story in his own way, especially as the life of Blackburne must

practically be the history of English chess for the last thirty years.

He was born at Manchester on the 10th of December,

1842—the same year as that in which Staunton's handbook was published, that is

to say, at a time when great interest was felt in chess. And yet it was not this

game but the simpler draughts that first engaged his attention. In those days

London did not possess her present superiority in games of skill. They were

almost monopolised by the north, at any rate the Trent may be said to have

divided the bad players from the good. From Manchester to Edinburgh it seemed as

if everybody knew about draughts. They could, at least, talk learnedly of the

openings, whose very names proclaimed the region in which they originated—the

Soutar, Laird and Lady, Ayrshire Lassie, Dyke, The Maid o' the Mill, all have

the North-country brand. I remember myself, as a boy, how excited the

Northumbrian villagers used to get over a contest between two local champions,

and how they celebrated the occasion by drinking beer from a huge vessel in

which it was the custom to have some penny "baps" and "wigs" floating. James

Wyllie, "the herd laddie," enjoyed that supreme reputation in his own game that

Roberts holds in billiards and Grace in cricket. It was a favourite pastime with

mill operatives and those who followed other sedentary occupations. Thus

Blackburne in a draught-playing country imbibed a love of the game with his

mother's milk, and he does not remember a time when he did not know how to "

huff" an opponent or crown a king. He was soon a capital draught player for his

years, and luck gave him the opportunity to try his skill in many quarters. His

father, in addition to other occupations, was a great temperance reformer in his

day, and when he went to Ireland or Scotland for the purpose of lecturing on

abstinence he took his boy with him. Joseph, in the manner of boys, proved more

heedful of his favourite game than of those paternal exhortations.

It was not till 1860 that he learned the moves of

chess. The year before all England had been set a-talking by the prodigious

feats of Paul Morphy, who played blindfold and upset veterans in match play, and

altogether flashed like a meteor across the chess world. Blackburne was infected

with the general enthusiasm. On his way home from work one day he picked up, for

two-pence, at a bookstall, a little book on the subject—he has utterly forgotten

name and author, but it was originally published in Edinburgh for a shilling.

From this he learned the moves, and judged that he was already equipped for an

encounter. But that was only the joyous confidence of youth. Chess was not so

popular then as now, and he had some difficulty in finding an opponent. He at

last discovered that in a sort of temperance hotel or coffee-house a number of

players were accustomed to meet once a week, and thither he resorted. As may

easily be imagined his first battle ended in disaster. He was sitting in a

profound meditation wondering if he distinctly remembered the Knight's move and

the correct method of castling when his opponent announced checkmate. But he

procured Staunton's handbook, studied the openings, played when he got a chance,

and in a very few weeks was giving odds to his whilom conqueror. He now joined

the Manchester Club, and beating one player after another soon came to hold a

leading place in it. The first thing to give him an idea of his own strength,

however, was his defeat of Pindar. This was the name of a well-known Russian

exile who had been long resident in Manchester, and was reckoned champion of the

Provinces. Happening to come by accident into the club one night he was pitted

against the young hero, and lost two games out of three. The very same thing

occurred again about a week afterwards. Various other little triumphs combined

to swell his local reputation. In Liverpool there was at the time a youthful

prodigy of his own age from whom great things were expected. The two were pitted

against one another at a match between the clubs and Blackburne won. His

opponent's name was Wellington, and the game has been preserved— it will be

found in the off-hand section of this book.

But the success that gratified him most—that yielded

more pleasure than many a subsequent performance—was his coming out first in the

Manchester Club Tournament of 1861-2. His runner-up was Horwitz, justly

celebrated for the precision and accuracy of his end play. It is to the early

lessons of Horwitz that Blackburne attributes his own proficiency in this part

of the game. This winning of the club championship practically brings to an end

one portion of Blackburne's career— that in which he figured as an amateur.

Events were shaping to bring him into the ranks of the professional.

There is a certain happy-go-lucky side to Mr.

Blackburne's character that must be reflected in his biography. Although in some

respects firm and resolute to a degree, he was not one of those who take the

helm in their own hands and, blow the wind as it may, doggedly make for a

certain point, but rather he spread his sails to the breeze, he floated on the

tide, he drifted before circumstances. It never was any ambition of his to

depend on chess for a livelihood, and probably he had no inherent love for that

kingdom of Bohemia wherein his tent has been continually pitched.

Two things combined to bring him into this career.

First, his fame was ever waxing greater, and in the year 1861 it happened that

Herr Paulsen came to Manchester on one of his blindfold itineraries. Blackburne

took a board, and was beaten in a very pretty game, which will be found in its

proper place in the book. The effect of this was to stir within him a great

desire to try blindfold play on his own account. The very next day he induced a

strong player to begin a contest in which Blackburne should not see the board.

He came off victorious, and shortly after played three opponents with the same

result. That was in the winter of 1861. In the spring of 1862 he engaged four

opponents successfully, the games produced being bright attractive specimens

that have been preserved, and will repay the trouble of playing over even

to-day. After that he challenged ten members of the Manchester Club, and emerged

with the fine score of five wins, two losses and three draws.

As may very well be imagined, these doings gave wings

to his reputation. The Manchester people believed they had found a genius, and

so competent a judge as Mr. Howard Staunton, the greatest player of his time,

said, in the Illustrated London News of 15th February, 1862 : " On this (the

first) occasion the unseeing performer was a young English amateur, who, without

any previous practice in blindfold chess, succeeded with perfect ease, and with

marked ability, in winning four games played simultaneously against as many

opponents ". Of the set of ten he remarked : " When it is considered that our

young countryman has had very little practice in chess play of any description,

and that in playing without seeing the board he is quite a novice, this last

exploit appears to us the most wonderful of its kind that has ever yet been

recorded ".

Just then arrangements were being made for the

Tournament of 1862, and naturally the admirers of Blackburne wished to see their

favourite take part in it. And this brings us to the second of the causes that

led him into professional chess. Neither he nor any one else appears to have

made any definite plan for the boy's future. His father by this time had taken

to photography, and the earliest work of the boy was to assist in producing the

daguerreotype then in vogue. But that was given up, and he had entered a hosiery

warehouse—a very useful calling, no doubt, but not likely to call forth devotion

or enthusiasm. At all events young Blackburne was engaged there when asked to

take a part in the great tournament of 1862. He accepted, but I doubt if in

doing so he was inspired chiefly with a love of chess. Bather he regarded it as

a pleasant outing. He had not previously been to London ; he wished to see the

great exhibition then on ; and, best of all, his expenses were paid. So he bade

what proved to be an eternal adieu to the hosiery business, and set out for the

first of the great chess struggles in which he was to take part. Before touching

on it, I may as well close the account of his very brief career as a business

man. It was the time of the cotton famine, and business was very dull in

Manchester. When he returned from his prolonged holiday his employers said that

his place had been filled up and his services were no longer required. He found

another situation, but, truth to tell, regular hours and desk work did not very

well suit his constitution, and the doctor told him that travelling was good for

his health. He had also found the air of Bohemia far from unpleasant, and so he

glided back to the alluring pastime.

The Tournament of 1862 had been promoted by the British

Chess Association, whose history was as follows : Before modern travelling

facilities were invented, it had been felt that country clubs were too much

isolated. The members played with the same opponents year in and year out ; they

adopted the style and peculiarities of their one best player ; enjoyed few

opportunities of measuring themselves with those outside their immediate circle,

and scarcely knew what first-class play really was. This did not suit the views

of the enthusiasts, and in 1840 a number of zealous Yorkshire players conceived

the idea of mustering a number of clubs for what seemed to their minds a grand

carnival—a whole day's play. Out of this was developed the Yorkshire Chess

Association, and from it in due time the British Chess Association. The meeting

of 1862 was the eighth held under its auspices, the seventh having assembled at

Bristol a year before. As this is being written, in 1899, London is again the

scene of an International Tournament, and we may well pause a moment to consider

what changes have taken place in the interval. And first there is that of the

men themselves. There are but two names that appear in both lists of players,

those of Mr. Blackburne and Herr Steinitz. But the Wonderful Boy of 1862, the

boy with an unknown and, because unknown, romantic future before him, is now a

grey veteran. As I saw him playing the youthful Maróczy I could not help

thinking how thirty-seven years ago he had played the aged Anderssen in pretty

much the same relative position as that in which Maróczy stood to him. Hard by

sat his life-long rival, Herr Steinitz, in 1862 also at the opening of his

career, and now bearing still more than Blackburne the impress of the years.

Then there is Mr. Bird, bent almost double, yet full of vitality—he was not in

the Tournament of 1862, though, nevertheless, in his prime. It may be useful,

however, to give the two lists for purposes of comparison.

Players In The Tournament Of 1862.

Foreign.

English.

Herr Anderssen.

Mr. Barnes.

Herr Löwenthal.

Mr. Blackburne.

Herr Paulsen.

Mr. Deacon.

Herr Steinitz.

Mr. Macdonald.

M. Dubois.

Mr. Mongredien.

Mr. Owen.

Mr. Green.

Mr. Robey.

Mr. Hannah.

Like many other tournaments, it was as remarkable for

the names left out as for those included. To mention a few, Paul Morphy was out,

and Bird and Boden, Heydebrand, Petroff, Jaenish, Harrwitz, Kolisch, St. Amant,

Journoud, Laroche and Max Lange. There was also a handicap won by Captain

Mackenzie, to whom Anderssen gave Pawn and move. To-day a new generation of

players has sprung up, but they are nearly all foreign, as will be seen by

comparing the two lists. Here are the names of the players in the Tournament of

1899 :—

Players In The London Tournament Of 1899.

Foreign.

English.

Herr Lasker.

Mr. Blackburne.

Herr Marocsy.

Mr. Bird.

Herr Schlechter.

Mr. Lee.

M. Janowski.

Mr. Tinsley.

M. Tschigorin.

Herr Teichmann.

Herr Steinitz.

Herr Cohn.

Mr. Pillsbury.

Mr. Showalter.

Mr. Mason.

And here, too, are many vacant places—Dr. Tarrasch and

Walbrodt and Lipke and Charousek and Burns, for example. It will be observed

that the English contingent is composed of middle-aged or elderly men, whereas

the most conspicuous foreign masters are young. The pursuit of chess is not

sufficiently lucrative to attract talented English lads, though the number and

ability of our amateurs show that the game is more popular with us than ever it

was before.

A change of manners as well as of men has taken place,

and some of the regulations in force thirty years ago look quaint to-day, as,

for example : " Two-thirds of the players agreeing may compel Pawn to King's

fourth to be played on each side every game ". The minimum rate of play was

slow, viz., twenty moves in two hours, but yet it was enacted that " the game

shall be played out at a sitting ". Time was measured by sand-glasses. The chess

clock, which, by-the-by, was first suggested by Mr. Blackburne, had not yet come

into existence. For the first time, at this tournament was adopted the modern

system of every player playing at least one game with each other competitor.

It was not to be expected that Blackburne would do well

at this tournament, as his previous practice had all been with provincial

players, who were not so strong then as the same class is now, and this was the

first occasion on which he had met really strong men. He gave a taste of his

quality, however, by defeating Steinitz in the first encounter that ever took

place between them, but, finding his position hopeless, he withdrew at an early

date from the contest. Before that, however, he had given a blindfold display

that' once and for all established his reputation as an expert.

I can scarcely do better than quote from the book of

the tournament the contemporary account of this exhibition, and I do so the more

willingly because several of the distinguished men who opposed Mr. Blackburne

are still alive and remember the scene perfectly.

Friday, 4th July.—This day's proceedings were the most

brilliant of the series. It was the occasion on which Mr. Blackburne was to

exhibit his marvellous faculty of blindfold play. Much interest had been

excited, and speculation was rife as to the ability of a youth of nineteen to

achieve success in a department wherein Messrs. Morphy and Paulson so

pre-eminently shone. At an early hour, therefore, there was a large throng of

amateurs to witness the performance. At one o'clock Mr. Blackburne took his

seat, and all other preliminaries having been arranged as in Mr. Paulsen's case,

the blindfold player commenced by taking the move in all the games. In each case

it was Pawn to King's fourth. The following were his ten antagonists :—

1. Lord Eavensworth. 6. W. Chinnery, Esq.

2. H. T. Young, Esq. 7. J. P. Gillam, Esq.

3. W. J. Evelyn, Esq. 8. Eimington Wilson, Esq.

4. A. S. Pigott, Esq. 9. A. G. Howard,

Esq.

5. H. B. Parminter, Esq. 10. A. G. Puller, Esq.

There was a notable difference in the minds of the

spectators of this match and of those who looked on at Mr. Paulsen's feat. In

the latter case there was the certainty that what had been promised would be

performed, Mr. Paulsen having often given proof of his wonderful capacity. But

amongst those who came to see Mr. Blackburne play there was a slight nervous

feeling that possibly the young athlete had over-estimated or over-taxed his

powers, and that some unlucky mistake, occurring at a critical moment, might so

confuse him as to render him incapable of further effort. As the games

proceeded, however, it became evident to all present that no apprehension need

be entertained. The rapidity and precision of his moves elicited universal

admiration, it being remarked that he seemed to play with greater ease than even

Mr. Paulsen. An incident that occurred at Mr. Evelyn's board still further

heightened the gratification of the spectators. A certain move on the part of

Mr. Evelyn was announced to Mr. Blackburne ; this he pronounced to be

impossible, great curiosity being excited as to the party liable for the error.

The moves from the beginning of the game were then called by Mr. Blackburne from

memory, and it was then discovered that the position on the board was wrong. The

rectification of this error drew forth loud cheers from all sides.

After Mr. Chinnery struck his flag there remained but

one antagonist, Mr. Puller. No better fate than that of the majority awaited

this gentleman. At a quarter to eleven o'clock, amid the loud and long-continued

applause that greeted him, Mr. Blackburne won this game also, swelling the list

of the vanquished to five. The final score was :—

Blackburne - - - - - - 5

His adversaries - - - -2

Drawn - - - - - - - - - 3

The result was a genuine triumph. Nothing could exceed the enthusiasm which was

evoked at the conclusion of an effort that rivalled the performances of the

greatest masters in this peculiar department.

I have at some length described the Tournament of 1862

because it is the starting-point of Mr. Blackburne's career as a professional

player of chess. He did not, however, rush into chess all at once. It will be

noticed that while 1862 and 1863 are well represented in the games, the

subsequent years up to 1867 are almost blank. During that period he played very

little in public, but gave his attention largely to business. It will interest

the reader to know that the inventive faculty which produces effects so charming

in chess was equally marked in other pursuits. Mr. Blackburne is pre-eminently a

man of ideas, and has either suggested or vastly improved several useful

mechanical contrivances as well as new games. Had the commercial instincts been

equally developed, he might have made a fortune out of them, but where he sowed

others reaped the harvest. The power to do things is not always joined to an

aptitude for taking advantage of it.

One congress is so like another that it would be

tedious to go through them all with the same detail, especially as the list of

successes concluding this brief account gives nearly all that is required. In

the notes to the games Mr. Blackburne has himself touched upon many a vivid

little incident connected with them. His life naturally divides itself into

three parts. First there are those great contests occurring almost annually and

consuming nearly two months of every year. In the second place comes his

experience as an itinerant performer, and thirdly, the ordinary day-by-day

existence of a chess player in London that would be hum-drum were it not so

curiously Bohemian.

As a tournament player Blackburne never has had an

equal, if regard be paid to the long period during which he has held his place

in the first rank. He has never failed to secure a prize, and that in itself is

a great deal to say when we consider how much a man's form must vary in the

course of forty years. Often he has been at the top, and even when not there has

generally managed to distinguish himself by a fine victory over his more

fortunate competitors. The beautiful game in which he defeated Herr Lasker in

the 1899 contest may be cited as an example. Indeed it is a noteworthy

circumstance that his most brilliant combinations have been produced against his

strongest opponents. It was so in 1867, when, defending the King's Gambit

against Neumann, the winner of the tournament, he played one of the greatest

games on record, and it was equally so in 1899. The same thing is true of his

blindfold and simultaneous games—the best of them are against the most skilful

players.

Apart from the game itself there is not much incident

connected with chess tournaments, but that of 1870 was an exception. The

International Congress was held that year at Baden-Baden, and while the players

were conducting their mimic warfare on the boards, France and Germany were

making ready for the terrible conflict that left Sedan and Metz and Paris with

new historical associations. While the players were engaged in conducting their

various gambits and openings, troops were marching, and war correspondents

hurrying, to Baden-Baden, where the French were expected. Most of the players

had in the end to scuttle off home in hot haste, and Blackburne himself was

arrested as a French spy. It would not have been a serious adventure to any one

but a peace-loving chess player. On one of his bye-days he had made an excursion

to Radstadt, and was calmly ordering dinner in his hotel when a German officer

entered, placed two sentinels at the door, and asked to see his papers.

Blackburne was then told—though with perfect civility—that he must consider

himself under arrest, and would not be permitted either to communicate with any

one or leave the hotel that night. Next morning, however, the carriage was

brought to the door, and he was not only released, but the whole of his expenses

at the hotel and back to Baden-Baden were paid. The only change he noticed was

that the conveyance had a new driver, and it afterwards turned out that the Jehu

who had acted in that capacity the night before was really a French spy, who in

this disguise had hoped to enter the fortified town of Radstadt. It is a

contrast on which a philosopher might enlarge—that of grown men producing mimic

strife with little wooden kings and queens, while living princes were leading

two great nations to the stern arbitrament of war. A reference to the Evans

Gambit played between Blackburne and Steinitz will convince any one that the

concentration of the players was not interrupted by any outside disturbance got

up by Bismarck and Napoleon.

Blackburne does not easily become excited. They used to

call him " the giant," " the man with the iron nerves " and " Black Death,"

phrases which show how he differs from the average chess player. Most of the

proficients are small in stature, and a great number are emotional. Indeed it is

almost pathetic to note what a contrast there is between the beginning and end

of a contest. The competitors go forth to battle all gay and light-hearted ; the

vain full of swagger, and the merry with jests on their lips. But after two or

three weeks the hard fighting begins to tell. To one who plays chess for

amusement only the inside of a congress room then becomes a revelation and no

pleasant one. The brainwork and anxiety develop all the physical weaknesses of

the players ; if a man has an infirmity he becomes more infirm ; if he is

subject to disease the disease is almost certain to attack him. Mr. Blackburne

is no exception to this rule, and the end of a congress generally brings on the

bronchial complaint from which he has suffered so much. And the development of

physical weaknesses is the least of it. The mental strain produces effects still

more disagreeable. These modern gladiators, though they wage war only with

harmless bits of wood, engage in as cruel a conflict as ever did those who

wielded the sword and the retiarius. Not only money and fame, but even

the means of livelihood depend on the issue, and when the last games come to be

played, and those who have hoped against hope begin to see at last that victory

is not for them, dejection and depression seize even on the light-hearted, and

losers have been found sobbing like children in the corridors. On the other hand

I can fancy I see old Anderssen leaning on his stick and flinging his hat in the

air with joy when sure of the first prize, and Maróczy clapped his hands with

boyish glee when he won the last of his games in 1899.

Mr. Blackburne seems scarcely to know what nervousness

is. When a hard-fought game is trembling in the balance the limbs of many

players twitch and quiver with excitement, some break out into a heavy sweat,

others stare at the table as if trying to penetrate it. But let the game go well

or ill the face of Blackburne wears always the same impenetrable mask. There was

a description published of him in the book of the Vienna tournament of 1873,

which, allowing for the changes made by the years, might stand for to-day. Says

the writer : " The pale, lean, muscular young man opposite is the iron

Blackburne, the Black Death of chess players. But very seldom there falls from

his moustache-covered lips a laconic English word. He surveys the game with the

eye of a hawk ; even now he is tearing to bits a snare laid for him by his

unsuccessful opponent, and a demure smile steals over his face."

In personal matches Mr. Blackburne has not been so

successful as in tournament play. He has, it is true, won many ; but he has lost

on several important occasions, and attempts have frequently been made to

explain why.

In chess it is exactly the same as in literature—talent

is always more sure of success than genius. The most ordinary " wood-shifter,"

by long study and analysis, can acquire a steady defensive style of

wood-shifting, and if patient and fairly intelligent can work up to a high

standard of play. One of his sources of strength is that he depends entirely on

what, as a Scot would say, " is putten in wi' a spune ". Any man of sound, clear

common sense could become a chess player of the first rank, provided always that

the fire and shadow of passion and fancy did not interfere with the steady,

cold, calculating brain. But genius is something other, something beyond the

first rank, and it is rare in chess as it is in letters. You could count on one

hand all who deserve the name. I would go to the Café de la Régence for the

first, for Philidor is the leader of the moderns. Breslau would give us the

next, in point of time at all events ; but who shall decide whether Anderssen

was greater or less than Paul Morphy? With these the subject of this memoir

deserves a place. He, too, has something beyond a talent for the game—he has

genius. And I by no means say that this gift is always a blessing to its

possessor. Talent is more under command, is more manageable, and while it is

content to labour, genius has a haughty self-reliance that is not always

justified. But just as one would never dream of admitting a man's name into the

brief list of great writers simply on account of a vast sale of books, so the

genius of a chess player is demonstrated not by his victories but by the quality

of his play. A modern match, indeed, is largely a trial of patience. Each

competitor gets up an opening—a safe and sound one like the Buy Lopez or the

Queen's Gambit—and day after day toils at its variations. Genius will never

shine at that task—you might as well harness Pegasus to a broomstick.

There is no chess contest in this country that excites

keener interest than the annual match by cable with America. It originated in a

struggle between the Manhattan and British Chess Clubs, but some one had the

happy thought of giving this an international character. For various reasons it

is very popular. The prize is honour and honour alone as far as the individual

player is concerned, and it is well understood that both nations do their utmost

to put their best team in the field. Mr. Blackburne has always played top board

on these occasions against Mr. Pillsbury, the champion of America, and is seen

at his very best in them. Out of four contests he has drawn twice and won twice.

I shall not easily forget the scene that occurred in the Hotel Cecil in 1899.

England had done badly. Several of our players after obtaining the best of it

had allowed victory to slip through their fingers, and at eight o'clock we did

not seem likely to win a game. The only possible chance lay with Blackburne, and

he had a position where the advantage was so infinitesimal, if advantage there

was at all, that in ordinary cases the game would have ended in a draw. At one

time it was being analysed on at least twenty boards, for it seemed as though

all the chess talent of London was there that night. But no sooner did any one

prove a win than somebody else demonstrated there was no win. Of course, all

this was unknown to the player, who sat behind the ropes smoking his pipe and no

doubt meditating what could be done with the position. He never played an end

game better, and the enthusiasm was something to remember when at last Pillsbury

was compelled to resign. In was one of those well-fought struggles that

Englishmen always love to witness.

On several occasions Mr. Blackburne has been invited to

go abroad and exhibit his marvellous powers of blindfold play—one of the most

remarkable of these excursions being that to Habana in 1891. Asked by a

cablegram, directed to Simpson's, if he would care to visit the famous club

there, he answered with a concise " yes," and travelling via New York in due

time arrived. He played two set matches, one with Senor Golmayo, the champion of

Spain, and the other with Senor Vázquez, the first player of Mexico, winning

both. The respective scores were, in the first match :—

Blackburne - - 5

Golmayo - - - 3

Drawn - - - -- 2

Total - - - - - 10

And in the second :—

Blackburne - 5

Vázquez - - - 1

Total - - - - - 6

During the seventh game with Golmayo a curious incident

occurred. The Spaniard had played a Scotch Gambit, and, by a queer coincidence,

a party in an adjoining room were amusing themselves with Scottish airs. "

Scotland is always to the fore," said Mr. Blackburne, as he was losing, and "

Scotland for ever and ever," sang out Senor Machado and other onlookers.

On this occasion Mr. Blackburne also took part in a

number of interesting consultation games, and also played a set of six blindfold

games. Of the latter he won four, lost none and drew two. Specimens alike of the

blindfold, match and consultation games will be found in their respective places

in the book. It was, on the whole, a pleasant and successful visit.

On the other hand it was severe illness that led to his

Australian tour in 1885. For a long time his life was almost despaired of as he

suffered, among other things, from congestion of the lungs. The doctor ordered a

long sea voyage, so that he went for health and not for the purpose of playing

chess. Being there, however, he received many requests to exhibit his power as a

blindfold player, and that this was not impaired will be evident from the scores

he made, and the selection of games which will be found within these covers.

Earlier than that he had, on the invitation of the

Dutch players, visited Rotterdam and the Hague, where he engaged most of the

prominent players in blindfold play. A set played at Rotterdam was afterwards

edited and published in the form of a Dutch pamphlet, with very copious notes,

for which he supplied the material. At the Hague he played in the Orange Palace

six players, of whom the Prince of Orange was one. His Royal Highness proved

himself an amateur of no mean capacity.

No other great chess player is so well known in the

provinces as Mr. Blackburne, and this comes from his habit of making annual

tours for simultaneous and blindfold play. He began this as early as 1863. The

doctor told him, too, that travelling was essential to his health, and he knew

no other way of getting about than by offering to visit clubs for blindfold

play. He is always welcome and always popular. Before his day it was customary

to make a solemn function of these exhibitions—Löwenthal, whose very name will

suggest a hundred droll stories to chess players,—went in full dress, and was as

silent and pompous as a father confessor. He was shocked when Blackburne flung

these traditions to the wind, met his audience in ordinary apparel, and all the

time he was playing bubbled over with chaff and irony all his own. Very

entertaining is it now to hear him when in the vein calling up reminiscences of

these journeys, but they would lose half their attraction in print, because,

being a born mimic and possessor also of a dry, pungent wit, his way of telling

such stories is the life of them. He is at his very best when playing two or

three stiff simultaneous games, his brain screwed to concert pitch in his

endeavour to find one of these ingenious mates that render his games so

delightful, throwing off jests as a bye-product, so to speak.

One can imagine that he needs some relief to the hard,

continuous brain-work. He calculates that since 1861 he has played no fewer than

50,000 games at chess, and I think the estimate is probably under rather than

over the real figure. A brief calculation will show my reason for so believing.

He goes off on his chief tour early in October and does not return till

Christmas, beginning another early in January. During the autumn of 1898—and it

was no exceptional season—he played close on 1100 games. The record of a single

week's play will enable the reader to judge for himself. It is for a week in

January, 1889, and is no more than representative of hundreds of other weeks.

On the 19th he played 29 simultaneously at the

Manchester Athenaeum.

Result—23 won, 4 lost, 2

drawn.

On the 21st he played 30 games simultaneously at

Newcastle-on-Tyne.

Result—20 won, 3 lost, 7

drawn ;

the draws due to want of

time on the part of his opponents.

On the 22nd, at the same place, he played 8

simultaneously blindfold.

Result—5 won, 3 drawn.

On the 24th he played 30 simultaneously at Manchester

Reform Club.

Result—23 won, 1 lost, 6

drawn.

On the 25th he played 20 simultaneously at the St.

Anne's Club, Manchester.

Result—14 won, 4 lost, 2

drawn.

In one week, therefore, he played 117 games in public, of which eight were

blindfold.

Between 1st October and 25th December he, as a rule,

has played from 1000 to 1100 games. January and February are equally

busy, and during the succeeding months his engagements are irregular, so that it

is a fair estimate that he has been in the habit of playing at least 2000 games

a year. If allowance be. made for the few seasons during which illness or some

other cause kept him at home, it will be seen that his estimate of the total

cannot be very far out.

These journeys have given him a unique knowledge of

English players and their style. In some respects these have changed greatly

during the last twenty years. At first, when he used to travel, and to some

extent even yet, it was like going from circle to circle. Each group modelled

itself on the strongest local player. If he happened to be of the safe and

cautious type most of the others were so likewise ; if he were dashing and

brilliant, lively games were the order of the day. Recently, however, the

multiplication of chess columns in the newspapers and the frequency of

inter-club play has tended to modify this state of things. He illustrates this

by reference to the famous Blackburne trap, as it is popularly called: He used

to catch three or four a night in it, whereas now every tyro is up to the dodge.

As a matter of fact the particular mate was first produced by M. de Kermar, Sire

de Legal, in 1702, in a game wherein he gave the odds of Queen's Rook. It was he

that taught the great Philidor to play. The game was as follows, and I give a

diagram to show the trap :—

White.

Black.

M. de Legal. His opponent.

1. P-K4 1. P-K4

2. B-B4 2. P-Q3

3. Kt-KB3 3. Kt - QB 3

4 Kt-B3 4. B-Kt5

5 KtxP5

Black to make his 5th move.

Black.

White—Legal.

5. BxQ

6 BxP + 6. K-K2

7 Kt-Q 5 mate.

It looks a very simple affair, but the position may arise in a variety of ways.

Chess players will remember that in the match played at St. Petersburg during

the winter of 1893, between Dr. Tarrasch and M. Tschigorin, the Eussian champion

was caught in it on the tenth move of the fifth game, the position being as

follows : —

Black—Tschigorin.

White—Tarrasch.

Tarrasch played Kt x P, and though Tschigorin is too

experienced a player to pounce on the exposed Queen his

game was irretrievable. But that such a thing should occur in first-class play

renders it the less wonderful that Blackburne should have had great fun with his

famous trap in the provinces. Often the victim steps in while he is even on the

look-out for it, and many of us know and remember the affectation of surprise,

the little start, with which Mr. Blackburne appears to discern that he has left

his Queen en prise, and the suavity with which successive checks follow.

Yet, although this is his fun, he carries on any number of strong, sound games

along with it, and despite the education afforded by the press and the general

improvement in play, he holds his own now as well as ever he did. I remember, on

the 23rd of December, 1898, being present while he played thirty members of the

City of London Chess Club. Among1 them were several strong amateurs who play

well up in the matches of what is probably the strongest club in the world. He

did not lose a game and drew only five. Moreover, he won the rest in beautiful

style, conducting at once half a dozen endings that were immensely admired for

their ingenuity and beauty.

Except for the everlasting strain on nerve and brain

all this wandering with its incessant change and variety would be by no means

unpleasant. A great chess player in our day has an opportunity of observing men

and manners of many different places. There are few countries in Europe wherein

Mr. Blackburne has not played chess, and, as will be seen from the games, not

many towns in Great Britain where his is not a familiar figure. It only remains

to describe as briefly as may be the life of a chess player in London.

I sometimes think that Mr. Blackburne is ultimus

Romanorum the last of the great English chess players. The generation to which

he belonged is dying out and another is not arising. Yet the paradox is that

chess never before was so popular or the number of clever amateurs greater.

Scarcely a year passes, for instance, without the universities producing a fine

player, and many that are excellent spring up at the clubs. But they never

become more than first-class amateurs. At an international tournament one is

struck by the number of young foreign masters and the absence of new faces from

this country. Without exception our representative players are past their prime,

while Lasker, Pillsbury, Janowski, Maróczy, Lipke, Charousek, are all young. As

the ability of our youthful players is beyond question, we can only attribute

their standing out to the fact that professional chess does not offer a

sufficient pecuniary inducement. The fact is, that a man with brains enough to

become a chess player of the first rank has a hundred better chances of earning

a livelihood here. For it is curious that the most intellectual pastime yields

the least return to its professionals. This country pays more for muscle than

brain. Cricket, football, boxing, billiards, golf—anything is better than chess.

I by no means say this is to be deplored, and the advice of any sensible man to

a lad meditating on this career would be that of Punch to those about to

marry—Don't. But the fact that we have no young man who can be looked to as a

successor of Blackburne is worth noting.

One reason probably is that it is a game which has

usually been played for small stakes. Among amateurs, indeed, there is seldom a

wager on chess. In Simpson's famous divan in the Strand, where, in their time,

Staunton and Buckle, and Zukertort and Steinitz have played, the old traditions

are kept alive, and a stranger entering is solicited to play for a shilling a

game. However, not many masters of the first rank condescend to that, and, in

point of fact, the playing of all-comers for small sums of money has been

practically discontinued by men of chess reputation. A more admirable and useful

practice is for a club to engage a master as coach. In this capacity Mr. Black-

burne acted while living at Hastings, and the results were excellent in every

way. The club in London with which he is most closely connected is the City of

London, of which the president is Sir George Newnes, a patron of chess and a

player of no mean capacity. Since 1867 Mr. Blackburne has taken an active

interest in it. The City of London Chess Club, as far as the number of players

and their playing strength are concerned, is undoubtedly the strongest in the

world at the present moment (1899).

Simpson's was the great and almost only chess resort

when he began playing in 1862. The Philidorian rooms and Purssells were,

however, still in existence. The Divan now has many rivals, and where there used

to be one chess resort in London there now are hundreds.

Into the details of Mr. Blackburne's life outside of

chess it would not be proper to go in the case of one who, as this is written,

is not only well and strong, but holding his own against young and old in the

International Tournament at the Aquarium, and as capable as ever he was of

baffling his adversaries with a combination. Besides, it seems to me that the

biographical interest of his life centres in 1862, when the young lad from the

country, not dowered with superior education or advantages of any kind, came up

to London and played ten good players at chess blindfold. The whole landscape

was all in front of him then, and of a hundred sunny tracks it was a question

which he should follow. It lies behind now, but the games show where the path

led. I think he has derived pleasure from fighting his old battles over again

and recalling in his vivid way the scenes and incidents by which they were

accompanied. There is many a chess friend in whom these pages will stir similar

recollections.

Mr. Blackburne's Successes.

The following is a list of the more important

distinctions won by Mr. Blackburne in the course of his chess career. I begin

with the one in Manchester because, though the least, it was the first, and

probably he never was so proud of another victory as he was of this :—

1861-2 Won first prize in Manchester Club Tourney. Horwitz second.

1868 The B. C. A. Challenge Cup and Championship of England. De Vere tied, but

Blackburne won in the play off.

1870 He divided third prize with Neumann in the International Tournament at

Baden-Baden. Anderssen and Steinitz first and second.

1872 Second in London Tournament. Steinitz first, Zukertort, De Vere and

Macdonell tying for third place.

1873 Second at Vienna—this was where the German called him the "Black Death" of

chess players. Blackburne ought to have been first as he beat Steinitz in the

match, and if he had vanquished his last opponent, Rosenthal, would have been

the winner of the tourney. He turned unwell, however, and lost this game,

letting Steinitz tie, and still being ill ho lost to Steinitz in the play off.

1876 First at Divan Tournament. Zukertort second, Potter third.

1878 Third at Paris. Zukertort and Winawer had tied for first and the former won

the tie match.

1879 Defeated Bird in a match by 5 to 2.

1880 First with Englisch and Schwarz at Wiesbaden Tournament—there were sixteen

entries.

1881 First at Berlin, followed by Zukertort, Tschigorin and Winawer. This was a

splendid victory as Blackburne had three games to spare at the end. In the same

year he defeated Gunsberg in a match wherein he allowed his opponent two games

start.

1882 Sixth prize at Vienna.

1883 Third prize in London Tournament—that was the year in which Zukertort was

first, followed by Steinitz.

" " Second at Nuremberg—only half a point divided him

from the first— Winawer.

1885 Second at Hamburg. In hunting parlance, a blanket could have covered all

the players at the end. Gunsberg was first, then, only half a point behind, came

a group of five, viz., Blackburne, Englisch, Mason, Tarrasch and Weiss.

" " First at Hereford International. Schallop and Bird

tied for second place, Mackenzie was fourth.

1886 First in London B. C. A. Handicap Tournament. Bird and Gunsberg tied for

second. „ First in " Criterion " Tournament. Burn second.

1887 Defeated Zukertort by 5 to 1 and 7 draws.

" " Second prize, tied with Weiss, at Frankfort

International Tournament.

Mackenzie first. „ Third prize, London B. C. A. Burn and Gunsberg tied for

first.

1888 Sixth at Bradford.

" " Defeated Bird in a match by 4 to 1.

1889 Fourth Prize at New York—he played splendidly at the beginning and came out

top at the end of the first round, but went quite out of form in the middle of

the second round.

1890 Defeated Lee by 6 to 2 and 7 draws.

" " Second prize at Manchester International. Tarrasch

was first, Bird and Mackenzie tied for third.

1891 Defeated the Spanish champion, Golmayo, by 5 to 3 and ? draw, and also

Vázquez, the champion of Brazil, by 5 to 1.

1892 Second in Five Players' Tournament—Lasker first—at British Chess Club. „

First in Black and White Tourney. Special prize for best score against

prize-winners at Dresden. 1894 Fourth prize at Leipzig International Tournament.

1896 Special prize for best score against prize-winners at Nuremberg.

1897 Third prize at Berlin.

1898 Special prize for best score against prize-winners at Vienna.

1899 Sixth prize at London International Tournament.

|