|

Hastings, England - 1908

One of the most famous chess

tournaments of all time took place at the site where William the Conqueror

invaded England and fought the history-altering Battle of Hastings in

1066. The tournament held in Hastings in 1895 was equally hard fought and

history-altering, relative to the chess world.

In 1882, the residents of this port town formed the Hastings & St. Leonards

Chess Club. The club grew and by the mid 1890s was able to, by virtue of

substantial guaranteed prizes contributed by wealthy residents - which

was doubled by contributions throughout England, attract the greatest names in

chess to participate in their annual chess festival. This tournament was held at

the Brassey Institute (now the Hastings Public Library, pictured

above) and all the participants (except Pillsbury) stayed at the Queen's

Hotel, where the Chess Club itself always met.

The tournament was played from August 5th until September 4th.

The seaside Queen's

Hotel in Hastings (1909)

There were several things that made

this tournament special, but the quality of the participants heads the list.

Attracted by the prize fund [ £150 ($750), £115 ($575), £85

($425), £60 ($300), £40 ($200), £30 ($150) and £20 ($100) and £1 ($5) per

win for non prize winners (and double for any win against one of the top three

prize winners); a special prize of a ring and a

copy of Carlo Salvioli's Theory and Practice of Chess (Teoria e

pratica del giuoco degli scacchi, 1877) went to whoever won the most Evans

Gambits as either black or white; the first player to secure seven wins received

a "richly produced, enlarged photograph of himself"; the non-prize-winner who

had the best score against the top seven winners earned himself $25; separate

unspecified cash prizes were given a Brilliancy Awards ] the entry list included the current World Champion, a

former World Champion, two former World Champion contenders and three future

World Champion contenders. The winner, Harry Nelson Pillsbury, was none of

these.

Pillsbury, sponsored by the

Brooklyn Chess Club, preferred not to stay with the other players feeling that

the distractions would interfere with his preparations. The 22 year old American

chess darling wasn't yet well known in the international chess scene and his

ultimate success took everyone by surprise.

Although Pillsbury became famous,

not just for his chess, but for his incredible photographic memory, it

noteworthy that the 23 year old Dutch player Norman Willem van Lennep whose

entry was rejected by the organizers but stayed in Hastings as a reserve player

and a journalist, also had a photographic memory. He would die just two years

later at age 25.

The result of the tournament:

-

Harry Nelson Pillsbury, 16.5

-

Mikhail Chigorin, 16.0

-

Emmanuel Lasker, 15.5

-

Siegbert Tarrasch, 14.0

-

Wilhelm Steinitz, 13.0

-

Emanuel Schiffers, 12.0

-

Curt von Bardeleben, 11.5

-

Richard Teichmann, 11.5

-

Carl Schlechter, 11.0

-

Joseph Henry Blackburne, 10.5

-

Carl Walbrodt, 10.0

-

Amos Burn, 9.5

-

David Janowski, 9.5

-

James Mason, 9.5

-

Henry Bird, 9.0

-

Isidor Gunsberg, 9.0

-

Adolf Albin, 8.5

-

Georg Marco, 8.5

-

William Pollock, 8.0

-

Jacques Mieses, 7.5

-

Samuel Tinsley, 7.5

-

Beniamino Vergani, 3.0

Young Geza Maróczy won the Minor

Tournament, while Lady Edith Thomas (the mother of Sir George Thomas), won the

Ladies' Tournament.

Hastings 1895

Front: Vergani, Steinitz, Tchigorin, Lasker, Pillsbury, Tarrasch, Mieses,

Teichmann

Back: Albin, Schlecter,

Janowski, Marco, Blackburne, Maroczy, Schiffers, Gunsberg, Burn, Tinsley

The Hastings Tournament has endured ever since

that time, making it the longest serial chess event. While several tournaments

were held in the Summer months, the tradition has been mainly the Hastings

Christmas Tournament. Tradition also has it that the participants annotate some

of their own games for the accompanying tournament books.

Picture from Pollock

Memories, edited and published by Mrs. Frideswide F. Rowland of Kingstown,

Ireland, Nov. 1889

William

Henry Krause Pollock was one of the lesser known participants in Hastings 1895 -

or maybe his shining light was just hard to see among such gleaming stars.

Unlike many of the players, Pollock was a complete amateur whose real profession

was medicine. He was born in Cheltenham, England in 1859 and earned his

licentiate from the Royal College of Surgeons in Dublin, Ireland in 1882. He

moved to Baltimore, Maryland in 1889, but returned to England in 1895. He

developed consumption, probably tuberculosis, and, after a brief

residence in Montreal, Canada in 1896, returned again to England where he died

on October 5 of that year at age 37. His main chess accomplishments were to win

the Irish Championship two years in succession (1885 and 1886), the second time

with a perfect score of 8/8, even against such players as Amos Burn and Joesph

Blackburne.

In Hastings 1895, Pollock came in

towards the bottom - 19th out of 22, winning 6, losing 10 and drawing 4 for a

score of 8/21. But his wins included games against 4th place Tarrasch

and 5th place Steinitz, no mean trick.

Pollock's win against Steinitz is

particularly interesting. Pillsbury, who lightly annotated the game for the

tournament book, called the ending, "rather an amusing finish to a very

interesting game." It's doubtful that Steinitz, who was more accustomed to

being the Amuser rather than the Amusée, was very much amused.

Pollock also annotated the game

(for BCM).

Notes by Pollock

(click each board once to activate)

| |

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6

3 Bc4 Bc5 4 c3

A favourite opening with Mr Steinitz in this tournament, in which he has

beautifully demonstrated the efficiency of some new ideas contained in the last

section of the Modern Chess Instructor.

4…Qe7

Strangely enough, this valid old defence of the days of

the Berlin ‘Pleiades’ has escaped all notice in the work referred to. A little

story comes in here: Previous to the championship match between Steinitz and

Lasker, at the request of the latter I played the defence to the Giuoco in a few

off-hand games with him at the Manhattan Chess Club. I adopted this old defence

without success, although Lasker admitted it was new to him. But I told him that

Steinitz would play it against him and beat him if he did not play the attack

differently. (It is no easy matter to reply correctly to Lasker’s bad moves.)

Lasker good humouredly suggested that we submit the theoretical question to

Showalter. However, he did not adopt this attack against Steinitz. The points of

the defence are well shown in the present game.

|

| |

5 d4 Bb6 6 a4 a5 7 O-O d6 8 d5

This is, as usual, a questionable

advance.

8…Nd8 9 Bd3 Nf6

White’s ninth move was in order to prevent

…f5. Without doubt Black should now have played for the advance by 9…g6.

|

| |

10 Na3 c6 11 Nc4 Bc7 12 Ne3 Nh5

If 12…cxd5 13 Bb5+, followed

by 14 Nxd5. Nor can Black well castle, on account of 13 Nh4, threatening to

establish a knight at f5.

13 g3 g6 14 b4

Intending no doubt 15 dxc6 bxc6 16 b5, when it would be

difficult to prevent the posting of the white knight at d5.

14…f5

It is necessary for Black to attack, but the situation is a

critical one. |

| |

15 Ng2

15 dxc6 might have been tried as an alternative to prevent

15…f4, for if then 15…f4 16 cxb7, followed by Bb5+ and Nd5.

15…cxd5 16 exd5

Preferable certainly seems 16 Bb5+ and if 16…Bd7 17

exf5, with the threat of Nxe5 or Bg5 presently.

16…Nf7

In order to keep the queen’s bishop out.

17 Re1 O-O

Black has now an excellent position.

|

| |

18 Nd4 Qf6 19 Nb5 Bb6 20 bxa5 Bxa5 21 Be2 Ng7 22 Bd2 Bd7 23 Rf1 Rac8 24 c4 Bb6

25 Be3 Bxe3 26 fxe3 Ng5

Of course an attack by …g5 might be on the

cards, but Black prefers the safer plan of …Ne4 and …Nc5, thus first securing

the queen’s side.

27 Nc3

Bad, as yielding the opponent a splendid opportunity

for a king’s side assault.

27... f4 |

| |

28 Qc2

If 28 gxf4 exf4, attacking the knight.

28…f3 29 Nh4

If the bishop moves, 29…Nh3+, followed by 30…fxg2+

29…Nf5 30 Rxf3

If 30 Nxf5 Bxf5 31 Bd3 f2+, etc.

30…Nxf3+ 31 Nxf3 Nxe3 32 Qb1 Nxc4 33 Ne4 Qd8

34 Qxb7 Na5 35 Qb4 Bg4 36

Rf1 Bh3 37 Re1 Rb8

38 Qxd6 Qxd6 39 Nxd6 Rb2 40 Bd1 Rg2+ 41 Kh1 Rf2 42 Ne4 R2xf3

43 Bxf3 Rxf3 44 d6 Rf1+ 45 Rxf1 Bxf1 46 Kg1 Bd3

Not 46…Bh3 on account

of 47 g4. |

| |

47 Nf6+ Kf7 48 Nxh7 Ke6 49 Kf2 Kxd6 50 Ke3 Bc2

51 h4 Nc4+ 52 Ke2 Kd5 53 g4 Kd4

The ending is a good one for the ‘gallery’; either the king or pawn must

advance with immediate effect.

54 Nf8 Bd3+ 55 Ke1 Ke3 56 h5 gxh5

Unnecessary; Black has a mate in four moves here.

57 gxh5 Be2 58 Nd7 Na3 59

White resigns |

The game with Notes by Pillsbury:

Beniamino Vergani had come in second in the Italian championship to earn his

place in the Hastings tournament.

Samuel Tinsley (1847-1903) scored

even with Jacques Mieses. Tinsley was a chess correspondent of master's

strength. He was born in Barnet, a small town outside of London..

Harry

Nelson Pillsbury, who won the tournament, was a neophyte to international chess

and a dark horse candidate for winning. But he did win and in impressive style.

Dubbed the "Hero of Hastings," Pillsbury reached the apex of his chess career at

Hastings.

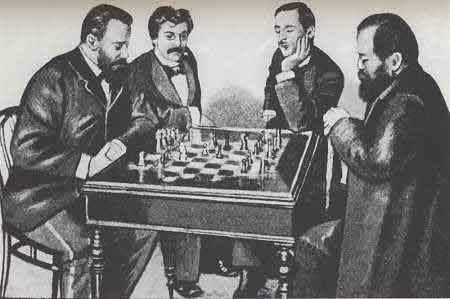

Steinitz

and Chigorin battle while Lasker and Pillsbury look on. Steinitz

and Chigorin battle while Lasker and Pillsbury look on.

|