|

VVV

VVV was a journal or magazine

developed by André Breton, along with Max Ernst and Marcel Duchamp, with David

Hare as editor and publisher. It only lasted 3 issues and it's primary purpose

was the dissemination of Surrealist ideas, or :

|

V+V+V. We say …_ …_...__

that is not only

V as a vow – and energy – to return to a habitable and conceivable

world, Victory over the forces of

regression and of death unloosed at present on the earth, but also V

beyond this first Victory, for this world

can no more and ought no more, be the same, V over that which tends to

perpetuate the enslavement of

man by man.

VV of the double Victory, V again over all that is opposed to the

emancipation of the spirit, of which the

first indispensable condition is the liberation of man

whence

VVV towards the emancipation of the spirit, through these necessary

stages: it is only in this that our activity

can recognize this end

Or again:

one knows that to

V which signifies the View around us, the eye turned towards the

external world, the conscious surface,

Some of us have not ceased to oppose

VV the View inside us, the eye turned toward the interior world and the

depths of the unconscious

whence

VVV towards a synthesis, in the third term, of these two Views, the

first V with its axis on the EGO, and the

reality principle, the second VV on the SELF and the pleasure principle

– the resolution of their

contradiction tending only to the continual, systematic enlargement of

the field of consciousness

towards a total view.

VVV

which translates all the reactions of the eternal upon the actual, of

the psychic upon the physical, and the

account of the myth in process of formation beneath the VEIL of

happenings. |

Irene Hoffmann wrote a

series of essays on Surrealism. One essay describes VVV:

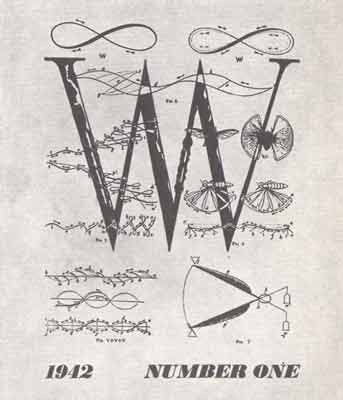

Another New York journal that

represented Surrealism was VVV, published by the young American sculptor

David Hare. With Breton, Ernst, and Duchamp as editorial advisors, VVV gave

exiled Surrealist writers and artists great exposure in the United States.

Modeled on Minotaure and more substantial than View, VVV's three issues

feature "Poetry, plastic arts, anthropology, sociology, psychology." The

first issue (October 1942) has a cover design by Ernst and includes writing

by Breton. Reflecting new connections within the New York art community,

this issue also featured contributions by artist Robert Motherwell and

critic Harold Rosenberg. The next issue, a double number (March 1943), has

front and back covers by Duchamp.

The front cover is an anonymous etching representing an allegory of death

that Duchamp appropriated. The back cover features the shape of a woman's

profile cut out of the cover with a piece of chicken wire inserted in the

opening. The final issue of VVV (February 1944) is similarly creative and

dynamic. With a bold cover designed by Matta, this issue features many

fold-out pages of varying sizes, a combination of different papers, and many

color images.

In addition to extending the life of the Surrealist movement, American

reviews such as View and VVV provided a forum for communication between the

Surrealists and a growing number of emerging American artists. For artists

who later would make up the Abstract Expressionist group, the Surrealists

were a significant and liberating influence. While Surrealism's potency was

in decline by this time, artists of the next generation would continue to

explore its tenets.

Although neither Dada nor Surrealism revolutionized society as profoundly as

their proponents had hoped, they left an indelible mark on art and writing.

These iconoclastic impulses of these movements remain rich sources of

artistic inspiration. The remarkable journals they generated have preserved

a detailed record of the revolutionary atmosphere in which they were

conceived and generated. Through their journals, the Dadaists and

Surrealists defined and broadcast their views of the world, and expressed

their hopes to transform and liberate art and culture. For admirers of the

rich and revolutionary ideas of these movements, these journals offer unique

insights into the minds of their creators.

In the OralHistory section of the

Archives of American Art, Robert Motherwell, who was involved with VVV

tells us:

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, what about

VVV magazine? Weren't you involved with that at some point?

ROBERT MOTHERWELL: Yes.

PAUL CUMMINGS: How did that come about? There weren't a lot of issues of that,

were there?

ROBERT MOTHERWELL: No. I'll tell you what I remember - and there's a lot I

don't remember. in

France before the war I think Skira - but I'm not sure - published an

extremely elaborate deluxe art

magazine called Minotaure that increasingly became a vehicle for the

Surrealists. The Surrealists were

proselyters. Which the other artists weren't at all. They very badly wanted a

vehicle here. By hook or by

crook slowly some money was raised. The actual editor was André Breton who

always was the chief of

everything surrealist. I think Marcel Duchamp and max Ernst if I remember were

associate editors. But the

Surrealists had a feeling - not really realizing that artists in America are

not taken very seriously - that they

were politically radical, etcetera, they were aliens, exiles, etcetera, and

that ostensibly there should be an

American editor. There was also some effort to get some Americans to

contribute. William Carlos Williams

and so on. And so for a time I accepted the role simply to help them out. Then

one day it became clear to

me in an angry discussion in French, which I only partly understood, that they

had also assumed that I had

American connections and could raise some money. Which I didn't have, and

couldn't. Then I got furious

and resigned. And the compromise was that Lionel Abel and I co-edited. And

then what transpired was that

Abel, who had no job, no money, no anything, asked for the colossal sum of

twenty-five dollars a week

simply in order to exist while he was gathering the manuscripts and all the

rest of it. And again, they got

furious at that and fired him. Then I said, "I resign." Then David hare who

had, I think, an independent

income agreed to be the nominal editor. Something very interesting to me that

always amuses me is how the

name VVV came about. They wanted to invent a twenty-seventh letter in the

alphabet. In French the letter

W is double V (VV). And so they hit on the idea of having triple V (VVV) as

the twenty-seventh letter. And

Breton also didn't know a word of English. And as sort of their American

adviser, lieutenant, liaison officer,

I pointed out to him that for reasons I didn't understand double V in English

is pronounced double U so that

it would not translate; in English you would have to call it triple U when

nevertheless the sign was three V's

and it really wouldn't work. He would not accept that it wouldn't work. And it

used to confuse everybody.

People didn't know whether to say V-V-V or triple V or triple U or whatever.

But if it were literally

transcribed into English the proper title would have been triple U. And the

fact that they choose V with the

way that English-speaking people say V made it not translate. Well, if you

said triple U the name of the

magazine immediately Americans would have got the point. But it was always

called triple V and nobody

got the point. It seems senseless.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, it's like the classic V U V combination.

ROBERT MOTHERWELL: Yes, exactly

Although David Hare was the editor,

Breton maintained strict control of the content. Breton, who flatly refused to

learn English, found a backer, Bernard Ries, an accountant and art lover, who

lived on 67th St. Editorial meetings were held

there, or at P. Guggenheim's apartment or at Breton place off Washington Square,

which Breton ruled with an iron fist.

|