|

Lawrence

Totaro noted some references to Chess and composer/artist John Cage within

the book, Conversing with Cage

Conversing with Cage. Contributors: Richard Kostelanetz -

author. Publisher: Routledge. Place of Publication: New York. Publication Year:

2003.

Page 5

Schoenberg was approaching sixty when I became one of his

students in 1933. At the time what one did was to choose between Stravinsky

and Schoenberg. So, after studying for two years with his first American

student, Adolph Weiss, I went to see him in Los Angeles. He said, “You

probably can’t afford my price, ” and I said, “You don’t need to mention it

because I don’t have any money. ” So he said, “Will you devote your life to

music?” and I said I would. And though people might feel, because I know my

work is controversial, that I have not devoted myself to music utterly, that I

have spent too much time with chess, or with mushrooms, or writing, I still

think I’ve remained faithful. You can stay with music while you’re hunting

mushrooms. It’s a curious idea perhaps, but a mushroom grows for such a short

time and if you happen to come across it when it’s fresh it’s like coming upon

a sound which also lives a short time. —Jeff Goldberg (1976)

Page 12

To continue with Duchamp a bit: Was he a good chess teacher?

I was using chess as a pretext to be with him. I didn’t learn, unfortunately,

while he was alive to play well. I play better now, although I still don’t

play very well. But I play well enough now that he would be pleased, if he

knew that I was playing better. So that when he would instruct me in chess,

rather than thinking about it in terms of chess, I thought about it in terms

of Oriental thought. Also he said, for instance, don’t just play your side of

the game, play both sides. That’s a brilliant remark and something people

spend their lives trying to learn—not just in chess, but everything. —Paul

Cummings (1974)

Page 18

Why do you have such a strong interest in chess, which is a

rigid, closed system?

In order to let it act as a balance to my interest in chance. I think the same

thing is true of Marcel Duchamp. Because when he gave me his book on chess, I

asked him to write something in it, and he wrote in French : “Dear John, Look

out, still one more poisonous mushroom. ” Because both mushrooms and chess,

you see, are the opposite of chance operations. —Art Lange (1977)

[Chess] is pretty directed then?

Yes. On the other hand, I like games anyway. I even like poker. I don’t play

it very often. Sometimes if you get in residence at a university you have to

play games with the teachers. Poker is very popular at universities. —Mark

Bloch (1987)

I spend most of the day working. Sometimes I interrupt my work to go mushroom

hunting or to play chess, which I don’t have a gift for. Marcel Duchamp once

watched me playing and became indignant when I didn’t win. He accused me of

not wanting to win. You must have an extraordinary aggressiveness to play

well. —Jeff Goldberg (1976)

Page 32

So you don’t have any real secrets about how you manage all

this?

Well, you begin by watering the plants, and you end the day by playing chess.

And I have to do my exercises. And I shop, generally, though I didn’t do that

today.

So by having a game of chess at the end of the day…

I’m making a balance with my use of chance operations. Because if I make a

wrong move with my knight, I lose. Games are very serious success-and-failure

situations, whereas the use of chance operations is very free of concern. It’s

like being enlightened. —Kathleen Burch et al. (1986)

Page 185

Later, it must have been in the early sixties, it just

happened that one holiday season between Christmas and New Year’s, when there

are so many parties in New York, we happened to be invited to the same

parties. Suddenly, I saw him every night, four nights in a row; and I noticed

there was a beauty about his face that one associates, say, with coming death

or, say, with a Velásquez painting. And I realized suddenly that I was foolish

not to be with him, and that there was little time left. And so I said to

Teeny [Mme. Duchamp], “Do you think Marcel would be willing to teach me to

play chess?” Because I knew that that would be a way to be with him without

asking him questions; or if I asked him questions, they would be ones it would

be useful to know the answers to. And so she said, “Why don’t you ask him

yourself. ” So I went up to him and said, “Would you teach me chess?” And he

said, “Do you know the moves; do you know how the pieces move?” And I said,

“Yes, I know that”; and he said yes. And so we made an appointment, then, for

me to go to his house; and after that, we were together as often as possible,

at least once a week when they were in New York, or sometimes twice a week.

—Alain Jouffroy and Robert Cordier (1974)

Page 214-215

My two closest friends among [visual] artists are [Robert]

Rauschenberg and [Jasper] Johns. And I knew many of the other painters, but my

kind of family attachment is to Rauschenberg and Johns. And then I always

admired Duchamp so much that I couldn’t speak straight and about four or five

years ago, I asked him to teach me chess, so I often was with him in his last

years, and I love his work very much. Originally, I had liked abstract

painting, and particularly Mondrian. And then it was Rauschenberg who opened

my eyes to the possibility of something that wasn’t abstract and then it’s

been so interesting because it was then Johns. I see Johns now more than any

of the others. I like, let’s see, of the ones since then, I think Claes

Oldenburg. —Don Finegan et al. (1969)

Page 219

[The conceptual artist William Anastasi, whose career began in

the early 60s, is probably best known for playing chess with John Cage everyday

in the late 70's.]

[Bill] Anastasi?

We play chess every day. We’re going to play today, and he’ll either drive

down or he’ll take the subway. If he comes down the subway, he’ll bring

headphones without music, and papers and a board to draw on, and pencils and

so forth; and he’ll make a drawing with his eyes closed, and his arms

responding to the movement of the subway car. —Richard Kostelanetz (1991)

What can you say about John Cage?

A revolutionary composer, just as his friend Marcel Duchamp was

a revolutionary artist, he was also, like Duchamp, an artist and a chess-player.

It's difficult to explore Cage's chess connection without including Duchamp.

Chessbase featured an interview with Prof. Enrique Irazoqui, "An economist

and a professor of literature, he is also an expert in information technology

and artificial intelligence. For many years he edited a magazine on computer

chess – in the end in electronic form. He always loved chess and has played

against Marcel Duchamp, who was a master class chess player." Prof. Irazoqui

lives in Cadaqués, which was also the home to famous artists, writers and

intellectuals such as Picasso, Miro, Duchamp, Cage and Dalí, who "during all

this time, in the cafes next to the sea, they played chess."

When asked about his chess associations with Duchamp and Cage, he responded:

How was it to play with Duchamp?

For me it was a pleasure but I am not sure it did him very

well. He usually finished being very upset. Teeny, his wife, asked me not to

play him any more because he would not sleep after that. It was tender, on a

way, very fragile. After that I mainly played with Teeny.

And John Cage?

He used to ask Raymond Keene to teach him how to defeat

Duchamp, but he never made it. I remember one day we were playing as usual,

in the Café, and he placed a pentagram of thin translucent paper on the

windows. He drew one note on top of each star and composed a melody of the

night. Fortunately I never heard it, but this gives you an idea of how were

these people and these days

The PBS American Masters Series claimed:

Many of Cage's ideas about what music could be were inspired

by Marcel Duchamp, who revolutionized twentieth-century art by presenting

everyday, unadulterated objects in museum settings as finished works of art,

which were called "found art," or ready-mades by later scholars. Like Duchamp,

Cage found music around him and did not necessarily rely on expressing

something from within.

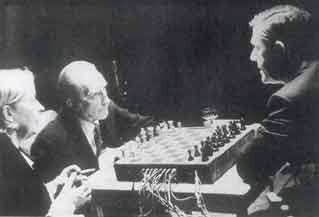

Marcel Duchamp and John Cage appear in a 1972 movie by that name. The linked

page offers this description:

PLOT DESCRIPTION

"Marcel Duchamp and John Cage" is both a document of a chess game and an

unusual theory on the nature of art. While Duchamp and Cage play chess,

Duchamp is filming the match according to a semi-random program of camera

placement, focus setting, and length of shot. The film is constructed like one

of Cage's musical compositions, and he talks at length about his esthetic

philosophies as well. ~ John Voorhees, All Movie Guide

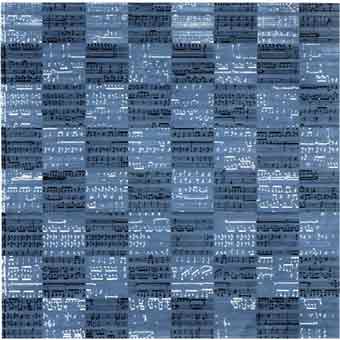

In 1944, Cage created a painting titled Chess Pieces that

contains a music. John Cage had been invited to participate in

The Imagery of Chess exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York

City ( along with such artists as Alexander Calder, Isamu Noguchi, Robert

Motherwell, André Breton, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Man Ray, Dorothea Tanning)

The music, interpreted by Margaret Leng Tan, is available

on the album, John Cage: The Works for Piano 7

Margaret Leng Tan, who worked with Cage for 12 years and

who performed the piano music on the album wrote, "There are 22 systems of

music, each 12 bars long and self-contained. So what you have are 22 little

'chess pieces,"

Reunión

Somewhere between Dream and Reality by Ya-Ling Chin explains:

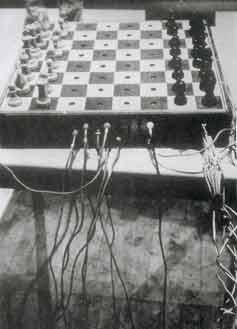

Performed at Ryerson Theatre of Ryerson Polytechnic, Toronto, on

March 5, 1968, Reunion was organized by John Cage and included the musicians

David Tudor, Gordon Mumma, and David Behrman and a wired-up chessboard designed

by Lowell Cross (Fig. 3). When Teeny and Marcel Duchamp took turns playing chess

with Cage on the stage, the pre-modulated photoreceptors served as a gating

mechanism to receive messages of movements and to transmit sound and light.

Depending on the moves of the chess pieces, the sound was cut off or rerouted to

generate a kind of random music by means of the pre-configured chance operation

of two "intellectual minds."

Lowell Crass had constructed a chess board with circuits; moves on the board

transmitted or cut off sound produced by several musicians.

From

John Cage - An Autobiographical Statement :

I was invited by Irwin Hollander to make lithographs. Actually

it was an idea Alice Weston had (Duchamp had died. I had been asked to say

something about him. Jasper Johns was also asked to do this. He said, "I don't

want to say anything about Marcel." I made Not Wanting to Say Anything About

Marcel: eight plexigrams and two lithographs. Whether this brought about the

invitation or not, I do not know.

From

Painting a picture of a creative partnership by Susan Mansfield :

Cage would say later that he had enjoyed both music and visual

art as a student, but that Schoenberg, under whom he studied in LA,

forced him to choose between them. "He said that if he wanted to be a

composer, he had to choose only music, which he did," says Miguel. "He didn't

make visual work for about 30 years."

However, in 1969, he made Not Wanting To Say Anything About Marcel, a work

using Plexiglas, as a response to the death of Marcel Duchamp. "He was in a

taxi with Jasper Johns and they were both asked to say something about

Duchamp, who had just died," says Miguel. "Neither of them wanted to say

anything, because nothing would have been enough.

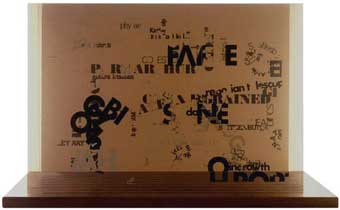

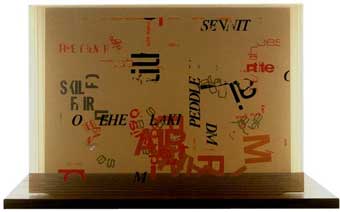

Not Wanting To Say Anything About Marcel, I, 1969

Not Wanting To Say Anything About Marcel, II, 1969

"Not Wanting to Say Anything About Marcel", 1969, "Lithograph B"

From

The Page is Not a Neutral Surface by poetess Jessica Smith :

John Cage’s Not Wanting to Say Anything about Marcel. A

stack of page-like glass rectangles, Not Wanting allows words to

fragment and accumulate in turn—depending, in some cases, on the reader’s

physical relation to the stack—and never allows one to take for granted any

unit of meaning. No phrases exist. Words fracture. Partial letters slip into

the murk of transparency. In the flatness of the pictures included in the

Poetry Plastique exhibition catalog (Granary Press), one can see or imagine

the three-dimensionality of the object, which itself takes advantage of all

three dimensions to allow words to hide behind each other or escape from their

strata depending on the viewpoint of the

reader.

After all, what can you say about John Cage? |