For almost 100 years, books based on Greco's

(Greco was nicknamed Il Calabrese) manuscripts - these books, the

first one printed in 1656, were called

Calabrians - were the prime

printed chess influence. Very little else of great significance or

influence was printed until Philidor's

L'Analyze des Echecs in

1749.

However, there were some noteworthy exceptions.

The first was Philip Stamma's

book, Essai sur le Jeu des

Echecs, published in Paris in 1737 and reprinted in Hague

1741. Stamma was a native of Aleppo, Syria. His pitch was that

chess spread into Europe from the Arab world, but that the Arabs

possessed secrets they had never passed on to the Europeans. Of

course, only he knew the secrets - which he might reveal, little

at a time, if properly compensated. The fact was that the "eastern

method of playing", as he referred to it, was stunted in

comparison to Europe. But Stamma wrangled a government job

(Interpreter of Foreign Languages to the British Government),

moved to England and played chess at

Slaughter's Coffeehouse

(est. 1692) in London. The members there encouraged him to reprint

his book again. He greatly expanded it and reprinted it in London

1745. Unfortunately for Stamma, in 1747 he agreed to a match at

Slaughter's against a relatively unknown player named

François-André Danican Philidor

who was so foolish he agreed to let all drawn games count

as wins for Stamma. Philidor won 8 - 2 (one of the losses was a

draw). In one match, Stamma's chess career was over and Philidor's

was begun.

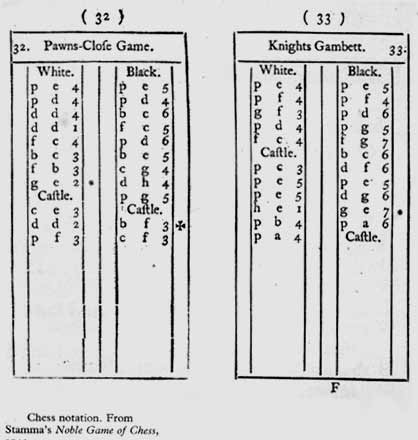

Philip Stamma, who at least was ahead of his time by using

algebraic notation, died around 1755.

Carlo Francesco Cozio

(born around 1715 - died around 1780) was the Italian Count of

Montiglio and Count of Salabue. He wrote

Il Giuoco degli Scacchi

around 1740. The book was in 2 volumes. The first volume contained

more openings and variation than any book prior -228 openings with

200 variations - many of which had never been seen in print

before. The second volume covered the various and different chess

rules used in Calabria at the time as well as endgame and

middlegame studies (201 endgames where examined) and chess

problems.

Cozio's Mate

There was still in Italy a chess movement to rival that in

France, though the Italian influence was almost finished. Around

1750, as Philidor was coming into prominence in France and

England, a trio of chessplayers/writers sprung up in Modena, a

town in northern Italy. They've come to be known as the

Modenese School.

The first of these was

Domenico Ercole del Rio - born in 1718 and died in 1802.

Del Rio was a lawyer by profession. Because he published

his first book, Sopra il Giuoco

degli Scacchi Osservazione Pratiche d'Anonimo Autore Modenese,

anonymously as the title suggests, he has been referred to as

the Anonymous Modenese. His book was 110 pages and later

expanded by his compatriot, Lolli.

Del Rio's other book,

La Guerra

degli Scacchi (The

War of the Chessman) was only published

in translation in 1984 by Christopher Becker.

Giambatista Lolli was

born in Nonántola, near Modena in 1698 (he died in 1769). A

reader of law by trade, he was the student and competitor of del

Rio. He wrote Osservazioni

Teorico-Pratiche Sopra il Giuoco degli Scacchi in 1763.

This was a huge extension of del Rio's work filling 632 pages.

The first part deals with openings, but all most half of the

opening theory deals with the Italian game. The part dealing

with endings was probably the best treatment to date,

particularly in R+B vs B and Q vs B+B endgames.

Lolli's Mate #1

Lolli's Mate #2

Domenico Lorenzo Ponziani

- 1719 to 1796 - was a law lecturer and a priest whose book,

Il Giuoco Incomparabile degli

Scacchi, 1769, deals with strategy as well as such

openings as the Vienna game and the Ponziani gambit and

countergambit. Ponziani's chapter dealing with chess authors

excited the interests of Baron

Tasillo von Heydebrand und der Lasa and steered him

towards his lifelong pursuit of historical research and book

collecting.

The Modenese School advocated the open game, particularly

the Italian game, favoring quick development above anything else.

Del Rio had read Philidor's book and disagreed with his approach

even to the point of including a criticism of Philidor's ideas in

Lolli's book. Because of the type of open game that the Modenese

School encouraged, they failed to grasp, or at least discounted,

Philidor's ideas of building a stronger center supported by pawns.