|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Mrs. Morphy is renowned in the

salons of New Orleans as a brilliant pianiste and musician; and her son, without

ever having studied music, has a similar aptitude for it, and he believes he

would have become as famous therein as in chess, had he given his attention to

it.

~Paul Morphy, Chess Champion by an Englishman (F. M. Edge)

p. 138

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Paul Morphy was raised in a musical

arena. His mother, Thelcide Le Carpentier Morphy, was a superlative musician

whose home was a Mecca for visiting notables of the music world as well as a

meeting place for the talent musicians of New Orleans.

Thelcide's granddaughter, Regina

Morphy-Voitier, in her late-life pamphlet on Morphy, wrote rather

matter-of-factly:

Almost every week,

Mrs. Morphy entertained large house parties, and her weekly "musicales" were

highly artistic and

enjoyable. Although Paul was not a musician in the true sense of the word, he

was noted for his splendid ear for music, and

once he heard a tune, he never forgot it, and he thoroughly enjoyed these

evenings devoted to classic music and brilliant

conversation. (p. 28)

Mrs. Morphy very often

contributed to the enjoyment of these gatherings by her talent, possessing a

magnificent voice. She

was noted as a composer, having composed many delightful trios for piano,

violin and 'cello. (p.37)

One of Mrs.

Morphy's piano students, as well as a close family friend, Léona Queyrouze,

painted a much more intricate picture in her unpublished manuscript, the

First and Last Days of Paul Morphy:

There were about forty-five music-stands at hand, in a closet adjoining the

music-hall; and on the grand concerto-days, they were all taken out and grouped

around the splendid Erard, which had been manufactured especially for Mrs.

Morphy and transported to her Louisiana home, with more solicitude than if it

had been a priceless jewel. It was exceedingly simple in appearance, and

destitute of a single ornament. It's value consisted entirely in it's wealth of

sound, and resided within the

plain rosewood frame, for the harmonies which issued from it were powerful and

thrilling.

There was a large and high music-hall in the house, so

constructed as to be intensely sonorous, and it had been fitted up in a way that

favored the reverberation of sound, which was not muffled and stifled by the

thick carpets; heavy draperies and encumbering furniture. Besides the piano, it

contained numerous light chairs, and a few massive music-stands of antiquated

style. There was also a vast rosewood book-case, filled with all the

master-pieces of classical music. When Herg, Thalberg and other celebrated

artists came to New-Orleans, it was there only that they found various works

which they had been unable to procure elsewhere in that city.

All kinds of musical instruments stood up against the

walls, or hung upon them in panophiles. Some of them were scattered pell-mell on

the chairs. Many years later, after Paul Morphy had become the king of

chess-players, several very fine engravings found their way into that room; and

in some of them he was seen playing with some famous champion. When he returned

from his first visit to Paris, he brought back to his mother a copy of his bust

- by the great sculptor Lequesne. It was proudly placed by her in her sanctum.

That copy, smaller than the original bust, also came from the hands of Lequesne

who presented it to Mr. Morphy, as a token of friendship and admiration.

On one side of the hall was the broad back-gallery,

protected from the sun's heat by the dense umbrage of the trees; and on the

other, the oval-shaped vestibule, through the lofty glass-dome of which the

light poured in, illuminating the music-hall

and showering aureoles upon the marble busts of Hayden, Mozart, Beethoven,

Weber and Mendelssohn, the divinities of that temple. Here and there, the

reflection of a golden beam was caught by one of the quaint old copper

music-stands, shaped in the form of a lyre, or lingered on some brass instrument

glittering in an obscure corner. At certain hours the room was all constellated

with stray sparks of sun. At night, the stars glowing in the luminous sky, and

the moon's tranquil rays, falling from the transparent dome and vaguely

whitening the darkness, imparted a weird aspect to the vestibule,

full of dusk and silence.

People, apparently,

were astonished by Morphy's ability to reproduce even the complicated score from

an opera after hearing it only once:

I asked his if his

nephew was remarkable for anything else than his peculiar aptitude for chess,

and I recollect that he stated,

among other things, that after his return from a strange opera he could hum or

whistle it from beginning to end.

~Dr. L. P. Meredith’s Letter in the Cincinnati Commercial - New

Orleans April 16, 1879

Almost every week, Mrs. Morphy

entertained large house parties, and her weekly "musicales" were highly

artistic and

enjoyable. Although Paul was not a musician in the true sense of the word, he

was noted for his splendid ear for music, and

once he heard a tune, he never forgot it, and he thoroughly enjoyed these

evenings devoted to classic music and brilliant

conversation.

~Life of Paul Morphy in the Vieux Carré of New Orleans and Abroad; p. 28

Morphy, after leaving the

theatre, hummed over many airs to me, which he had just heard for the first

time, with astonishing precision.

~Paul Morphy, Chess Champion by an Englishman (F. M.

Edge) p. 138

He was passionately fond of

music, and his memory in regard to it, was as prodigious as for chess. After

having once heard

any opera whatever, he could sing or whistle it almost through, with the

greatest facility and accuracy.

~First and Last Days of Paul Morphy

Morphy's first love

was the opera, but he wasn't limited to that particular musical form. Léona

Queyrouze described a moving encounter she had with Paul as he surreptitiously

watched her play the piano:

He was a worshipper of Beethoven, Weber and Mendelssohn; and when his light,

nervous step, so familiar to me, resounded in the sonorous vestibule, at one

o'clock, the time at which he came in from his promenade, I often stopped

practicing, and set aside scales and exercises for some of his favorite adagios,

andantes or scherzos. The doors of the music hall were always open, and when he

passed by it, he looked in with a smile, nodded and went.

He was particularly fond of "La Bella Capricciosa" ,

one of Hummel's most exquisite gems [Polonaise for Piano in B

flat major, Op. 55 La Bella capricciosa by Johann Nepomuk Hummel].

Chopin's morbidness affected him painfully, and there were very few of the

Polish master's works which I ventured to perform for him. One day, I was alone

in the music-hall playing the "Berceuse" [a lullaby].

After a short while, I felt that somebody else must be present, but I did not

heed that impression, thinking that it could only be Mrs. Morphy or her

daughter. It grew more forcible every second, and at length I was irresistibly

impelled to turn around and look, before I had concluded that ideal composition.

Leaning against the black marble mantlepiece, under the large engraving which

represented him in one of his brilliant games with Louis Paulsen, both

surrounded by renowned amateurs, there stood Paul Morphy, silent and pale, with

tears trickling down his wan cheeks. I shall never forget that sight. Neither of

us spoke, and he immediately withdrew from my presence.

It was like an apparition.

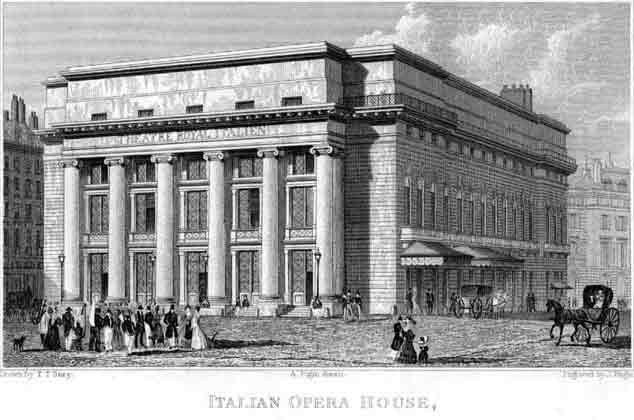

Le Théâtre-Italien, Paris c.1850

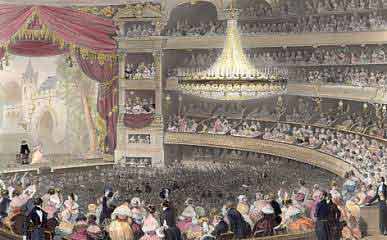

The interior of the Théâtre-Italien

Inside a Box in the Théâtre-Italien

During Morphy's triumphal

tour of Europe, one of his most famous games, as most chess enthusiasts know,

was played against the Duke of Brunswick and Count Isouard in the Duke's box at

the Italian Opera House, and has been dubbed the

Opera Game. There is

often some confusion which opera was being performed during this game. The cause

of this confusion is that Edge describes Morphy playing these two noblemen in

their first encounter at the opera during which Norma by Vincenzo Bellini was

being performed:

H. R. H. the Duke

of Brunswick is a thorough devotee to Caïssa; we never saw him but the was

playing chess with someone or other. We were frequent visitors to his box at the

Italian Opera; he had got a chess-board even there, and played throughout the

performance. The Duke's box is right on the stage; so close, indeed, that you

might kiss the prima donna without any trouble. Morphy say with his back

to the stage, and the Duke and Count Isouard facing him. Now it must not be

supposed that he was comfortable. Decidedly other wise; for I have already state

that he is passionately fond of music, and, under the circumstances, wished

chess at Pluto. The game began and went on: his antagonists had heard Norma

so often that they could, probably, sing it through without prompting; they did

not even listen to most of it, but went on disputing each other as to their next

move. Then Madame Pencho, who represented the Druidical priestess, kept looking

towards the box, wondering what was the cause of the excitement inside; little

dreaming that Caïssa was the only Casta Diva the inmates cared about. And

those tremendous fellows, the "supes." who "did" the Druids, how they marched

down the stage, chaunting [sic] fire and bloodshed against

the Roman host, who, they appeared to think, were inside the Duke's box.

~Edge; pp. 154-155

However, as Edge

stated above, "We were frequent visitors to his box at the Italian

Opera." The Opera Game was played in one of their subsequent visits during

which Gioacchino Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia was performed.

On their first

visit in October they played chess throughout the entire performance of

Norma....

On the second of November they heard The Barber of Seville, during which Morphy

played his most famous game, the Duke again consulting with Count Isouard.

~Paul Morphy: The Pride and Sorrow of Chess by David

Lawson; pp. 159-160

Lawson's

assertion was affirmed via Edward Winter's Chess Note #2895 which reported that

"Christian Sánchez has consulted the fortnightly magazine L’Univers Musical

of October and November 1858. He reports that although Morphy’s name did not

appear, the 16 October and 1 November numbers mentioned that the October

performances at the Théâtre-Italien included

Norma, while the 15

November issue stated that

The Barber of Seville

had been performed that month. This schedule is in line with the information

quoted from Lawson’s book."

The Opéra Comique of Paris

In the

evening we went to the Opéra Comique, and witnessed a very unsatisfactory

performance of "La Part du Diable."

Morphy has a great love for music and his memory for any air he has once heard

us astonishing. Mrs. Morphy is renowned

in the salons of New Orleans as a brilliant pianiste and musician; and her son,

without ever having studied music, has a

similar aptitude for it, and he believes he would have become as famous therein

as in chess, had he given his attention to it.

"La Part du Diable" was a new opera, and Morphy, after leaving the theatre,

hummed over many airs to me, which he had

just heard for the first time, with astonishing precision.

~Paul Morphy, Chess Champion

by an Englishman (F. M. Edge)

le Théâtre d'Opéra de la Nouvelle Orléans, 1880

Returning to New Orleans, Morphy

inserted himself into the routines of haute société which included regular

attendance at the le Théâtre d'Opéra, known more commonly as the French Opera

House located on the corner of Bourbon and Toulouse streets.

Paul Morphy was

exceedingly fond of grand opera and very seldom missed a performance at the old

French Opera House

on Bourbon Street, which was unfortunately destroyed by fire in 1920. During

intermissions, he would call upon some of his

lady friends who occupied boxes and invite them to a promenade in the "foyer"

where refreshments were served.

~Life of Paul Morphy in the Vieux Carré of New Orleans and

Abroad; p. 28

Since the new Opera

House was built in 1859, Morphy had, of course, attended the old opera house,

but after the erection of the new one, the old building was used for less

prominent productions and was soon torn down.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

A Concise

History of the French Opera House of New Orleans

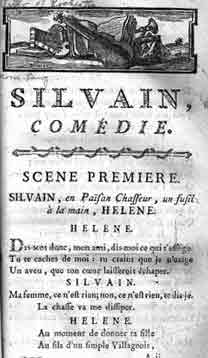

Le Théâtre d'Orléans 1819-1866

The first documented operatic performance in New Orleans, Silvain by Jean

François Marmontel, M. Grétry, took place on May 22, 1796. By 1809 there was an

actual opera season during which operas were regularly scheduled. A

building specifically for operas, le Théâtre d'Orléans, was constructed in

1815 by Louis Tabary (who came from Provence, France by way of Saint-Domingue

around 1805) but burned down the following year and was replaced in 1819 with

the building pictured above by John Davis, a New Orleans entrepreneur. Davis,

who came to New Orleans from France and as a refuge from Saint-Domingue,

had the property on Orleans Street (between Bourbon and Royal) locked-up with

control over the Davis Hotel, the Orleans Ballroom, and the Théâtre d'Orléans.

While the Théâtre d'Orléans catered to the Creole population, John Caldwell, an

Englishman in New Orleans, had built the Camp Street Théâtre mean to attract the

American population ("Americans" is a term often used to depict non-Creoles

living in New Orleans). As the two groups, Creoles and Americans, started to

homogenize, Caldwell and Davis became arch-rivals for the same dollars.

19th century New Orleans was highly susceptible to breakouts of

yellow fever. In 1819 alone there were

2,190 deaths from this

cause. To avoid this disease, as well as the heat and the possibility of cholera

and of hurricanes, many well-heeled families would leave the city during the

summer months. With this dwindled audience the opera cast originally disbanded

during the summer, but in 1826-27, Davis came up with the idea to mobilizing his

troupe and carry their talent to New York and Philadelphia where French drama

and opera were a rarity. Since New Orleans had a reputation for being the

premier operatic center in the U.S., the performances were quite welcomed.

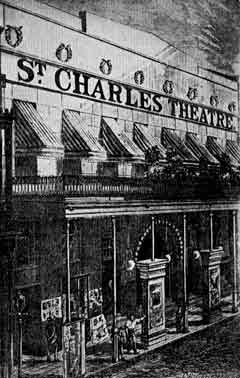

On November 30, 1835 John

Caldwell constructed a $325,000 behemoth with a 4100 seating capacity named the

St. Charles Théâtre (on St.Charles Street between Poydras and Gravier).

"Its front was 130 feet

wide, & the facade included a balustrade decorated with statues of Apollo & the

muses. Inside, the auditorium featured 4,000 seats, 47 boxes draped in crimson,

blue & yellow silk, and gilded columns flanking what was probably the largest

stage in the country -- ninety by ninety-five feet."

[see:

St. Charles Theatre]

It's most notable feature was "an enormous

chandelier 12 feet high & 30 feet in circumference of 23,000 crystal prisms

illuminated by 176 gas jets."

It's "productions were

popular and ran from the drama's classics of tragedy & comedy, to melodrama &

farces.... and to variety acts such as horse shows, acrobats, jugglers, singers

& comics." It also included opera, "importing Italian opera companies from

Havana, and further enriched the local repertoire by staging, again often for

the first time in this country, operas of Vincenzo Bellini (Norma, 1836),

Gaetano Donizetti (Parisina, 1837), and Rossini (Semiramide,

1837). [see:

New Orleans Opera]

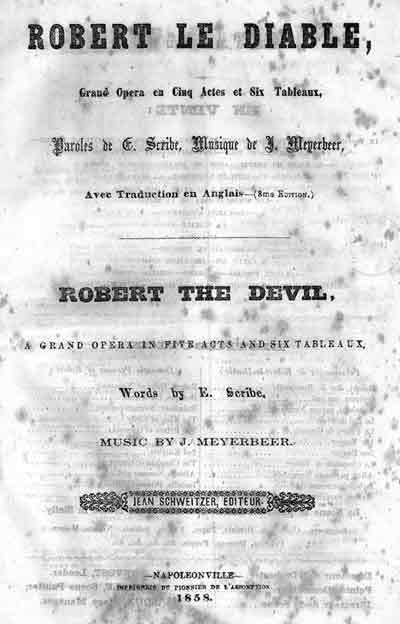

In 1835 James Caldwell put on an

English production of Robert Le Diable by Giacomo Meyerbeer at the

St. Charles Théâtre. Shortly after John Davis staged a French performance of the

same opera at the Théâtre d'Orléans. Calwell's version received high critical

reviews and better acceptance from the audiences.

Unfortunately St. Charles Théâtre

burned down on March 13, 1842 when a fire in the adjacent coffin factory

spread to the theatre. However, even though the theatre was immediately

rebuilt, this event solidified the operatic prominence of the Théâtre d'Orléans.

Davis soon took on a partner,

Charles Boudousquié.

In 1840 M.

Charles Boudousquié, who subsequently became the husband of the fascinating

Calvé, recruited in France the first important company of singers to visit New

Orleans. They arrived on the ship "Le Vaillant," after a voyage of sixty days,

and less than a week later made their appearance at the Theatre d'Orleans in

Adams' "Le Chalet," Lecourt, tenor, and Victor, baritone, appearing in the cast.

Boudousquié continued to direct the operatic performances at the Orleans till

1859. During that interval many important works were produced, among them

"Robert le Diable," in 1840; "William Tell," in 1846; "La Juive," in 1847;

"Jerusalem," p729"Lucie de Lammermoor," and "Le Prophete," in 1850; and "Les

Huguenots," in 1853.

[see:

Kendall's History of New Orleans; Ch. 45]

By 1853 Boudousquié

had almost autonomous control.

In 1859 the Theatre d'Orleans was sold to a Mr. Parlange. Boudousquié proposed

to continue the lease of the premises, but not being able to accept Mr.

Parlange's terms, announced his intention of abandoning the house. Mainly

through his exertions the French Opera House Association was incorporated March

4, 1859, with capital stock of $100,000, divided into 200 shares of $500 each.

Boudousquié himself was largely interested in the company. Rivière Gardère was

chosen president, and the first board of directors was composed of George

Urquhart, E. J. McCall, Charles Kock, Gustave Miltenberger, E. Roman, C.

Fellows, Charles Roman, Leon Queyrouze and Adolphe Schreiber. A site was

purchased at the corner of Bourbon and Toulouse streets, and the erection of the

present building was begun on April 9, 1859. The architect was James Gallier,

and the builders were Gallier & Esterbrook. The work was prosecuted by day and

by night, 150 men being kept constantly on duty. The building was completed

November 28, 1859, at a cost of $118,500.

In the meantime Boudousquié had, by a contract dated April 12,

1859, undertaken the lease of the new theater. He

associated with himself the veteran manager, John Davis. The opera house was

formally opened December 1, 1859 with

"Guillaume Tell." The principal singers were Mathieu, first tenor; Escarlate,

tenor of grand opera; Petit, third tenor;

Melchisadek, baritone; Genibrel, first basso; Vauliar, second basso; Mme. St.

Urbain, second falcon. Later during the

season "Le Trouvère" and "La Fille duº Regiment" were produced, and "La Tour de

Nesle," "La Dame Aux Camelias," and

other French plays were acted, in accordance with a tradition of which the opera

had not yet been able to shake itself free.

The season of 1860 was likewise successful. The same singers

appeared, with the exception that Mme. Brochard replaced Mme. St. Urbain,

falcon. On November 8, 1860, the opening night, "Le Barbier de Seville" was

presented with Mme. Faure in the role of Rosine. Among the operas which were

presented during this season were "La Favorite," "Il Trovatore," "La Juive" and

"Robert le Diable." Early in 1861 Adelina Patti made her first appearance at the

French Opera House, as Martha, in Flotow's opera of that name. During her

engagement Patti sang also in "Les Huguenots," "Robert le Diable," "Charles VI,"

and "Lucie." In 1862, 1863 and 1864, on account of the Civil war, there were no

performances at the Opera House.

In January, 1866, an Italian troupe, under the direction of Thioni

and Susini, gave a few performances. Paul Alhaiza then became director of the

opera. He recruited in France a very large and capable troupe, but the entire

membership was lost at sea, October 3, 1866, in the wreck of the steamer

"Evening Star." Of the 250 souls on board this ill-fated vessel, only

seven escaped. Among those who were lost were Gallier, architect of the opera

house, his wife and Mr. and Mrs. Charles

Alhaiza, relatives of the impresario. Mr. Alhaiza was, however, able, with the

assistance of several excellent artists, to open

the season on November 16, when Octave Feuillet's "La Redemption," a comedy in

five acts, was presented.

[see:

Kendall's History of New Orleans; Ch. 45]

The seating plan for the French Opera House (Théâtre

d'Opéra)

"In 1873 the rights

and titles of the original company were acquired by L. Placide Canonge for

$40,000, and Canonge, acting for a syndicate, resold to the Merchants' Insurance

Co., mortgage creditor. Canonge himself assumed the

management, which he retained till 1878."

L. Placide Canonge

was a confidante of Mrs. Morphy. According to Regina Morphy-Voitier, "She also

composed the music

for a five act opera entitled Louise de Lorraine, the words of which were

written by L. Placide Canonge, one of the most

brilliant men of New-Orleans, a journalist of talent, editor of L'Abeille de la

Nouvelle-Orleans, and also at one time

Impressario of the Theatre de l'Opera."

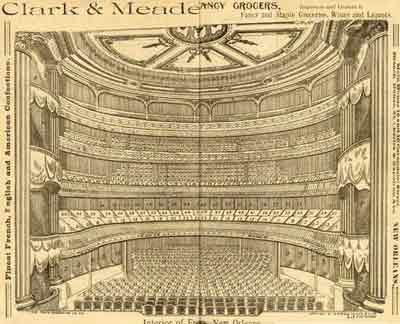

The Théâtre d'Opéra opened on

December 1, 1859

The opera

house was one of the most famous masterpieces designed by noted architect James

Gallier, architect of Gallier

Hall and many other classic 18th Century buildings. The great elliptical

auditorium was beautifully arranged with a color

scheme of red and white, and seated 1,800 persons in four tiers of seats. It was

Greek Revival in design, and its colonnaded

front measured 166 feet on bourbon Street and 187 feet on Toulouse Street. Its

80 foot high loft towered above all of the

buildings of the French Quarter. In the loges of the opera house, there were

screened boxes for pregnant ladies, ladies in

mourning, and "ladies-of-the-evening" (elegantly dressed madams from nearby

Storyville).

[see:

the History of The Inn on Bourbon

(built on the site of the Théâtre d'Opéra)]

and burned down on

December 4, 1919. |