|

Introduction

|

Time ago a crazy dream came

to me,

I dreamt I was walkin' in World War III,

I went to the doctor the very next day

To see what kinda words he could say.

He said it was a bad dream.

I wouldn't worry 'bout it none, though,

They were my own dreams and they're only in my head.

I said, "Hold it, Doc, a World War passed through my brain."

He said, "Nurse, get your pad, this boy's insane,"

He grabbed my arm, I said "Ouch!"

As I landed on the psychiatric couch,

He said, "Tell me about it."

-

Talking WWIII Blues by Bob Dylan |

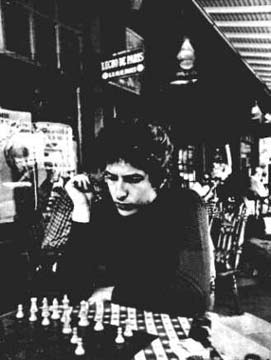

Bob Dylan - around 1962 |

The The above introduction juxtaposes some Bob Dylan song lyrics involving

psychoanalysis with a photograph of Dylan playing chess. One

might quite correctly observe the forced connection (the person of Bob Dylan)

between the two and question the validity of their inclusion, particularly their

conspicuous position in the introduction of this article on Chess and

Psychoanalysis. Really, there is no rational connection between Dylan's

funny/poignant song and the fact that he was a chess player, except that if I

could establish one, I might have all the natural abilities with which to become a

psychoanalyst.

The song ends:

Well, the doctor interrupted me

just about then,

Sayin, "Hey I've been havin' the same old dream!

But mine was a little different you see.

I dreamt that the only person left after the war was me.

I didn't see you around."

Well, now time passed and now it seems

Everybody's having them dreams.

Everybody sees themselves

Walkin' around with no one else.

"Half of the people can be part right all of the time;

Some of the people can be all right part of the time;

But all the people can't be all right all the time."

I think Abraham Lincoln said that.

"I'll let you be in my dreams if I can be in yours."

I said that.

I

played myself at chess last night.

My id was black, my ego white.

-SBC

Lawrence

Totaro recently bombarded me with a canister-and-grape flurry of chess

references specific to the field of psychoanalysis.

My own limited foray into this battlefield has been skirmishes with the

writings of

Ernest Jones and

Reuben Fine

on Paul Morphy and I restricted myself to exposing the flawed historic basis

(leading, presumably, to a flawed analysis) both of these Freudian analysts used

in insipidly trying to psychoanalyze, for whatever reason, a person long dead.

Whether the field of psychoanalysis is good, bad, helpful, chicanery or science,

is of no consequence here - our only purpose is to explore and document those

places where chess and psychoanalysis meet.

"There is a class of men—shadowy, unhappy, unreal-looking men—who gather in

coffee houses, and play with a desire that dieth not, and a fire that is not

quenched. These gather in clubs and play tournaments...but there are others

who have the vice who live in country places, in remote situations—curates,

schoolmasters, tax collectors—who must needs find some artificial vent for

their mental energy."

—H.G. Wells (concerning Chess)

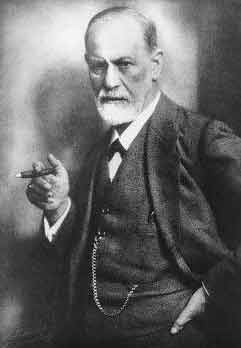

Sigmund Freud

“He who hopes to learn the fine

art of the game of chess from books will soon discover that only the

opening and closing moves of the game admit of exhaustive systematic

description, and that the endless variety of the moves which develop from

the opening defies description; the gap left in the instructions can only

be filled in by the zealous study of games fought out by master-hands.”

—Sigmund Freud

“At one point he likened it to

chess, where one can learn the opening moves and the end game moves, while

the middle game can be acquired only by actual practice and contact with

the games of great masters. Others since Freud have made many attempts to

systematize the teaching of psychoanalytic therapy more thoroughly, yet

there always remains a highly personal element in psychoanalysis which

makes it in a sense more of an art than an exact science.”

—Reuben Fine from

Freud: A Critical Re-Evaluation of

His Theories. Reuben D. Fine;

Publisher: David McKay. New York; 1962. Page 97. (Other books

by Fine: The Personality of the Asthmatic Child,

Psychoanalytic Observations on Chess and Chess

Masters)

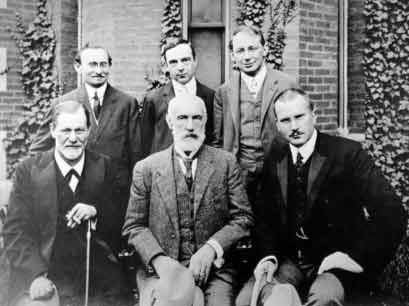

Distinguished Psychologists at Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts,

1909

(seated, front row): Sigmund Freud, Granville S.

Hall and Carl Jung;

(standing, back row): Abraham A. Brill, Ernest

Jones and Sándor Ferenczi.

Sigmund Freud: Four Centenary Addresses.

Ernest Jones; Basic Books; New York; 1956.

Page 90

If the leading chess player of

America can desert that fascinating occupation for the arduous life of a

psychoanalyst it is not surprising that anthropologists, art critics and

historians, not to mention educationists, have done the same.

The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud: Years of Maturity,

1901-1919. Volume: 2.

Ernest Jones; Basic Books; New York; 1953.

Page 235

(11) The next paper, "On Beginning

the Treatment," 24 published in January and March of the following year (

1913), dealt with the various problems that arise at the inception of the

treatment. This paper is full of worldly wisdom garnered from his years of

experience. What to say to the patient in the first interview, how much to

explain, arrangements about time and money, the suitability of various cases,

are among the matters he treated. Freud was always very apt at analogies, and

here he remarked that those who are learning "the noble game" of chess soon

find out that only the openings and the end game permit of systematic

presentation; much the same applies to a psychoanalysis. He admitted, however,

that even here the variations among patients are so great that none of the

rules he proposes has any absolute validity; they all may have to be altered

according to the case. One can only describe an average procedure.

Page 384

Freud played a good deal of chess

in coffee houses in the earlier years, but he came to find the concentration

more of a strain than an enjoyment, and after 1901 he gave it up altogether.

An evening spent at a theater was a rare event. It had to be something of

special interest to him, such as a performance of a Shakespeare play or a

Mozart opera before he could tear himself away from his work.

The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud: The Formative Years

and the Great Discoveries, 1856-1900. Volume: 1.

Ernest Jones - author; Basic Books; New York;1953.

Page 33

To return to the choice itself,

Freud had a very orderly mind (and also orderly habits), and his power of

organizing a mass of facts into a systematic grouping was truly remarkable;

his command of the literature on the subject of childhood paralyses, or on

that of dreams, is one example alone of this. But on the other hand he rather

spurned exactitude and precise definition as being either wearisome or

pedantic; he could never have been a mathematician or physicist or even an

expert solver of chess problems. He wrote easily, fluently, and spontaneously,

and would have found much rewriting irksome

Page 163

There were two quite distinct

groups of strictly personal friends: those he got to know in his medical and

scientific work, mostly older than himself; and a little group of about his

own age. The latter, fifteen or twenty in number, constituted what they called

the Bund (Union). They used to forgather regularly once a week in the Café

Kurzweil for conversation and games of cards and chess.

Page 329

Freud had one important hobby, but

few relaxations apart from holidays. He played a certain amount of chess, but

gave it up entirely before he was fifty since it demanded so much

concentration which he preferred to devote elsewhere. When alone he would

sometimes play patience, but there was a card game he became really fond of.

That was an old Viennese four-handed game called tarock. He was playing this

in the nineties, and probably earlier; later on it became an institution, and

every Saturday evening was religiously set aside for it.

Page 332

There is no point in giving a list

of twenty or thirty names, since none of them were of much importance to

Freud. His chief friends were Bloch, Oscar Rie, and Königstein. It was about

this time that he was giving up chess for tarock, the card game to which he

remained faithful; they would often play this until one or two in the morning.

When Freud spoke later of the ten years of isolation one must understand that

this referred purely to his scientific, not to his social, life.

Letters of Sigmund

Freud.

Ernst L. Freud - editor, Sigmund Freud - author, James Stern - transltr, Tania

Stern - transltr. Publisher: Basic Books; New York; 1960.

Pages 61-62

To Martha Bernays discussing the death of Freud’s friend,

Nathan Weiss

Vienna, Sunday September 16, 1883

“For fourteen years he hardly ever

left the hospital, whirled like a fast-moving automaton out of the building and

into the restaurant, into the coffeehouse, and back. His recreation consisted of

playing cards and chess, at which he was a master, and in spite of the agitation

it produced in him and which sometimes caused him to be exceedingly ruthless, it

was a pleasure comparable to a theater performance to watch him at play and to

listen to his original, biting wit.”

(Freud's colleague in the General Hospital who committed

suicide in 1883 L.T.)

Nathan Weiss

Page 100

To Martha Bernays

Vienna, Wednesday March 19, 1884

It grew more and more easy, after a

warm bath I could walk quite well, then I dashed into the laboratory, made up

my mind to start work again, in the afternoon played chess in the coffeehouse,

and on receiving a brief visit from Prof. Hammerschlag I decided to return it

in the evening. This I did; of course they were all rather concerned and soon

threw me out again, but here I am in the saddle once more, have no pains

despite the long day, only feelings of fatigue which is understandable, can

work again and am immensely, immensely pleased that I have recovered by my own

decision.

Freud: A Life for Our Time.

Peter Gay ; Norton; New York; 1998

Page 134

I give myself over to my

fantasies, play chess, read English novels; everything serious remains

banished. For two months not a line of what I am learning or surmising has

been put into writing. Hence I live as a sybaritic philistine as soon as I am

free of my trade. You know how constricted my indulgences are; I may not smoke

anything good, alcohol does nothing for me at all, I am done begetting

children, my contact with people has been cut off. Thus I vegetate, harmless,

taking care to keep my attention diverted from the theme I work on during the

day.

Page 295

FREUD'S PAPER "On Beginning the

Treatment," with its reassuring, reasonable tone, is representative of the

series as a whole; he was offering flexible suggestions rather than ironclad

edicts. The felicitous metaphor—chess openings—that he enlisted to elucidate

the strategic initial moment in psychoanalysis is calculated to woo his

readers; the chess player, after all, is not tied to a single, dictated line

of procedure. Indeed, Freud observed, it is only just that the psychoanalyst

should have some choices open to him: the histories of individual patients are

too diverse to permit the application of rigid, dogmatic rules. Still, Freud

left no doubt that certain tactics are plainly indicated: the analyst should

select his patients with due care, since not every sufferer is stable enough,

or intelligent enough, to sustain the rigors of the psychoanalytic situation.

It is best if patient and analyst have not met before, either socially or in a

medical setting—certainly one among his recommendations that Freud himself was

most inclined to flout. Then, the patient duly chosen and a starting time set,

the analyst is advised to take the initial meetings as an opportunity for

probing; for a week or so, he should reserve judgment on whether

psychoanalysis is in fact the treatment of choice.

Collected Papers. Volume: 2.

Contributors: Sigmund Freud - author, Joan Riviere - author; Basic Books;

New York; 1959

Page 342

FURTHER RECOMMENDATIONS IN THE

TECHNIQUE OF PSYCHO-ANALYSIS 1 ON BEGINNING THE TREATMENT. THE QUESTION OF THE

FIRST COMMUNICATIONS. THE DYNAMICS OF THE CURE. (1913)

H E who hopes to learn the fine

art of the game of chess from books will soon discover that only the opening

and closing moves of the game admit of exhaustive systematic description,

and that the endless variety of the moves which develop from the opening

defies description; the gap left in the instructions can only be filled in

by the zealous study of games fought out by master-hands. The rules which

can be laid down for the practical application of psychoanalysis in

treatment are subject to similar limitations.

I intend now to try to collect

together for the use of practicing analysts some of the rules for the

opening of the treatment. Among them there are some which may seem to be

mere details, as indeed they are. Their justification is that they are

simply rules of the game, acquiring their importance by their connection

with the whole plan of the game. I do well, however, to bring them forward

as 'recommendations' without claiming any unconditional acceptance for them.

Freud for Historians

Peter Gay; Oxford University Press; London; 1986

Page 88

If it is change, then, that makes

history possible; it is persistence that is the foundation of historical

understanding. Like the game of chess, human nature constructs dramatic and

inexhaustible variety from a few elements and a handful of rules.

Freud and Beyond: A History of Modern Psychoanalytic

Thought.

Contributors: Margaret J. Black - author, Stephen A. Mitchell - author;Basic

Books; New York; 1995

Page 58

The psychoanalytic process can be,

and has been, conceptualized in many different ways. The metaphors that are

chosen to illustrate principles of clinical technique often provide the best

indication of the underlying assumptions of each analytic model. Freud's

metaphors all have an adversarial quality: war, chess, hunting wild beasts. As

the ego psychologists shifted the focus from the id to the ego, from the

repressed to the central nexus of psychological processes, their models of the

analytic process also began to change.

The Childhood of Art: An Interpretation of Freud's

Aesthetics.

Contributors: Sarah Kofman - author, Winifred Woodhull - transltr.;

Columbia University Press; New York; 1988

Page 17

In "applying" psychoanalysis to

art, Freud advocates the murder of the father and his substitutes. Clearly,

the public worships the artist and all other "great men." Yet in Moses and

Monotheism, where Freud tries to define the nature of the great man, he

shows that no thinker, artist, technical expert, or great chess player is

worthy of the name. Success in a life of action is no more satisfactory as a

criterion, as Freud shows by deliberately citing the examples of Goethe,

Leonardo da Vinci, and Beethoven. The concept of the "great man" is vague, and

connotes nothing more than the presence of numerous human capabilities in the

individual so designated.

Why They Play: The Psychology of Chess

TIME magazine article (September 4th, 1972) by

Gilbert Cant

Manhattan's

Dr. Ariel Mengarini, a nonanalytic psychiatrist, asserts that the typical

amateur chess player has had a formal education and has a job that does not

come up to his intellectual capabilities. He needs the kind of mental workout

that he gets in chess. Equally important, to Mengarini, is the struggle. "But

the beauty of chess," he says, "is that the rules are clear-cut. If you win,

no one can take away your victory. In life, most of your wins are not

clear-cut. If you've lost, there's nothing to do but shake hands with your

opponent. This is most refreshing compared with most human relationships,

including the world of business and sexual relationships."

Another non-Freudian, Dr. Kurt Alfred Adler, son of the

late Alfred Adler and an exponent of his school of individual psychology, goes

further. "To me," he says, "chess is a game of training in orientation for

problem solving, not only in strategy and tactics and plane geometry, but in

learning to use the pieces as a cooperative team. I would put little emphasis

on the elements of hostility and aggression, and dismiss completely the sexual

symbolism. The players are trying to overcome difficulties, and while they are

also trying to attain mastery, the game is a form of social intercourse."

How much raw competitiveness enters into the game

depends on the culture, says Adler. In collective societies such as Russia,

the player plays the board rather than his opponent. Competitiveness becomes

more pronounced in Western Europe and is rampant in the U.S. Whether a player

plays the board or against his opponent becomes a finespun argument in the

tens of thousands of chess games that are always in progress by mail.

Biochemist Aaron Bendich, of Manhattan's Sloan-Kettering Institute, summarizes

his motivation: "I play as an intellectual exercise, and I don't see my

opponent as an adversary. But there is an adversary—and that's me! If I lose

and allow myself to get angry with my opponent, I am really projecting onto

him the anger I feel with myself for having played badly."

Chess, Oedipus, and the Mater Dolorosa

by Norman Reider, M.D.; International Journal of Psychoanalysis. XL, 1959

The psycho-analytic study of play

and games has been particularly rewarding, but no game is so full of

possibilities for such study as that of chess. Chess is the royal game for

many reasons. It crystallizes within its elaborate structure the family

romance, is replete with symbolism, and has rich potentialities for granting

satisfactions and for sublimation of drives. Not without reason is it the one

game that, since its invention around A.D. 600, has been played in most of the

world, has captivated the imagination and interest of millions, and has been

the source of great sorrows and great pleasures....

The first

paper on chess from the psycho-analytic point of view, presented to the Vienna

Psychoanalytic Society on 15 March, 1922 and duly recorded in the minutes, was

never published. Dr. Fokschaner, a dentist, entitled his paper, "Über das

Schachspiel." Hoffer recalls that it drew some parallels between chess and

obsessional neurosis, with an attempt to interpret symbolically the pieces and

their movements on the chessboard. In his discussion Freud was critical of

Fokschaner’s simplifications, and that ended the topic...

[Ernest]

Jones developed the thesis that chess is a game of father-murder, which became

the pattern for most psychoanalytic studies on the subject. Yet the same theme

was advanced by an earlier writer, Alexander Herbstman (35), whose work,

published in Moscow in 1925, could not have influenced the psychoanalytic

literature. Herbstman, a physician, and a chess problemist, made a systematic

study of the form and content of chess. He paid tribute to Freud, Sachs,

Ferenczi, Rank, Jung, Richlin, Abraham, and Jones for elucidating the

unconscious. He began his essay by considering the preoccupation of the game

with royal figures, especially the king and queen, and quoted Freud as

follows: "In dreams the parents assume a royal or imperial form as a couple.

You find a parallel to this in stories. ‘There lived once a king and a queen’

when obviously the account is about the father and mother." He then developed

the thesis that the whole play of the game is an elaboration in numerous

varieties and derivatives of the oedipal situation. To him the game consists

primarily of the king, queen, and pawn, with the other pieces being displaced

images of king or queen. Herbstman also discussed the concept of ambivalence

as represented in chess, analyzed some dreams of chess, and attempted to

explain certain early legends of chess, on the basis of the oedipal

conflict....

Other studies followed in

somewhat different directions. One is the use of clinical studies and

psychoanalytic therapy, as in Pfister’s work, the first convincing analysis

of the chess player by his chess play. Coriat discussed the general problem

of the symbolism of the pieces and also the way in which the styles or

habits of play revealed the players’ motivations. Fleming and Strong

reported the first systematic effort to use chess therapeutically in the

case of a 16 year old boy who worked through a problem of inhibition of

aggression by mastering the game, thus achieving a sort of belated mastery

over his own impulses. In another such study, Slap paid considerably more

attention to details of the ego factors involved in a patient’s

preoccupation with chess. The practicing psychoanalyst’s interest will often

lie in the clinical aspects of the game, and to him it should not be

surprising that a player’s interest in chess and his style of play reveal

dynamics consistent with his character structure; however, consideration

must also be given to the fact that the nature of skill in chess does not

depend only on derivatives of conflictual forces.

Another trend in pathobiography

was taken by Karpman and Fine, whose studies are biographical and

descriptive rather than clinical. Other psychoanalytic writings on the

subject, covering phases in the main described above, are by S. Davidson,

Menninger, and Ibanez. Menninger’s reflections on the game as a hobby are

unique in the sense that its informal therapeutic values are delightfully

discussed....

The

Unconscious Motives of Interest in Chess

Isador H. Coriat; Psychoanalytic Review; 1941

The

unconscious motive which actuates chess players is not the pugnacity which

characterizes competitive games, but the grimmer one of father-murder. The

King is not actually captured, as was customary in the original purpose of

earlier games, but the goal of modern chess is “sterilizing him into

immobility.” The game is pre-eminently of an anal-sadistic nature and so

gratifies the aggressive aspects of the antagonism between father and son; its

unconscious motivation is the symbolic expression of a “wish to overcome the

father in an acceptable way.”

It seems from the material cited that the chief symbolic feature of chess can

be compared with the aggressive aspect of the Oedipus complex. The capture of

the King by checkmate eliminates him from the combat, it ends the game, the

King is dead or castrated into immobility, an end result which corresponds

with what Oliver Wendell Homes terms “the brutality of an actual checkmate.”

The English word “checkmate” is derived from the Persian or Arabic and means

literally that the “King is dead,” paralyzed, helpless and defeated, which is

synonymous with murder or castration.

The Drive for Self: Alfred Adler and the Founding of Individual Psychology.

Edward Hoffman; Addison Wesley Publisher (Current Publisher: Perseus

Publishing); Reading, MA.;1996.

Page 86

Like Adler,

Trotsky enjoyed the Café Central as an incomparable institution of Viennese

life, exotically serving as home, office, and restaurant. When Count Leopold

von Berchtold, the Austro-Hungarian foreign minister from 1912 to 1915, was

told that a Communist revolution might erupt in czarist Russia, he exclaimed

with an incredulous guffaw, "And who, if you please, will make that

revolution? Mr. Bronstein [Trotsky] who is playing chess at the Central all

the time?" But the Café's famous headwaiter, Josef, is reported to have shown

no surprise upon hearing the news in 1917 that the Russian revolution had

broken out and that Trotsky was among its leaders. "I always knew that Herr

Doktor Bronstein would go far in life," quipped Josef, "but I shouldn't have

thought that he might leave without paying for the four coffees he owes me."

Adler enjoyed playing chess as a minor hobby, and may have sparred

occasionally with Trotsky. But he was finding himself busier than ever in

advancing a new psychological system that was becoming increasingly divergent

from the Freudian. Besides speaking at prestigious gatherings such as the

International Congress of Medical Psychology and Psychotherapy, Adler in 1913

published several important articles that further demarked his approach. These

included "On The Role of the Unconscious in the Neurosis," "New Principles for

the Practice of Individual Psychology," and especially,

"Individual-Psychological Treatment of the Neuroses."

Page 321

Another journalist anxiously asked, "Do you think my son's beating me at chess

means he's really got a better brain than I have?" Soothingly, Adler answered

that, "It might not be so. I myself have frequently been beaten by men who I

do not suppose were any more intelligent than myself. I have even known quite

stupid people who played chess well."

I'll let you

be in my dreams if I can be in yours.

|