|

"Chess... is eminently and emphatically

the philosopher's game"

-Paul Morphy-

The publisher of

The Cambridge Companion to Wittgenstein, tells us:

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) is one of the

most important, influential, and often-cited philosophers of the twentieth

century, yet he remains one of its most elusive and least accessible. The essays

in this volume address central themes in Wittgenstein’s writings on the

philosophy of mind, language, logic, and mathematics. They chart the development

of his work and clarify the connections between its different stages. The

contributors illuminate the character of the whole body of work by keeping a

tight focus on some key topics: the style of the philosophy, the conception of

grammar contained in it, rule-following, convention, logical necessity, the

self, and what Wittgenstein called, in a famous phrase, ‘forms of life’.

Additional Information on

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Wikipedia

The

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

A

comprehensive site on Wittgenstein

This article was written in its entirety by Lawrence Totaro of

Ultimate Chess Collecting

Ludwig Wittgenstein

(April 26, 1889 – April 29, 1951)

“I might say that chess would never have been invented apart from the

board, figures, etc. and perhaps apart from the connection with troops in

battle.”

On page 186 of The Immortal Game, David Shenk offers examples of three

prominent men in regards to their use of chess. He mentions at least one work

for each except for Ludwig Wittgenstein.

He writes about Richard Feynman: “The legendary American physicist and

physics teacher Richard Feynman relied heavily on chess in his lectures at the

California Institute of Technology (later published in the 1904 book Six Easy

Pieces: Essentials of Physics Explained by its Most Brilliant Teacher) to

help decode the scientific process for his students.”

As for Italo Calvino, Shenk goes on to write: “Italo Calvino, the whimsical

and postmodern Italian author of Cosmicomics, If on a Winter’s Night a

Traveler, and other influential fictions, was impressed by chess’s ability

to transform limitless data into a simple impression.”

The author continues: “Austrian-born British philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein,

regarded by many as the most important philosopher of the twentieth century, was

utterly fascinated by chess, referring to the game nearly two hundred times in

his writings.”

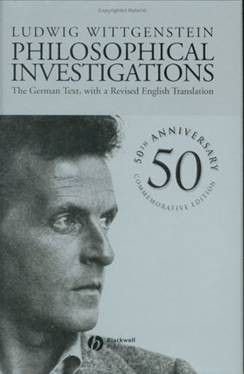

It should be noted that “in his writings” means the grandiose work titled,

Philosophical Investigations (1951, published posthumously) which mentions

chess to a large extent depending upon which publication you own. According to

the Blackwell published work he writes “chess” 181 times [see this excellent

paper by Steven B.

Gerrard] But not only is chess mentioned in Philosophical

Investigations; a popular excerpt is given below taken from, The Blue and

Brown Books:

a. "The meaning of a phrase for us is characterized by the use we make of it.

The meaning is not a mental accompaniment to the expression . . . I want to play

chess, and a man gives the white king a paper crown, leaving the use of the

piece unaltered, but telling me that the crown has a meaning to him in the game

. . . I say: "as long as it doesn't alter the use of the piece, it hasn't what I

call a meaning.""

Also keep in mind that Wittgenstein, considered by students and many

scholars, is considered “an Austrian philosopher” and not British as stated

above.

In Wittgenstein's Lectures: Cambridge, 1932-1935 (Edited by Alice

Ambrose) Wittgenstein mentions “chess” 54 times.

Below are some excerpts.

Page 3

“2. Words and chess pieces are analogous; knowing how to use a word is like

knowing how to move a chess piece. Now how do the rules enter into playing the

game? What is the different between playing the game and aimlessly moving the

pieces? I do not deny there is a difference, but I want to say that knowing

how a piece is to be used is not a particular state of mind which goes on

while the game goes on. the meaning of a word is to be defined by the rules

for its use, not by the feeling that attaches to the words.”

Page 101

“It is a fallacy to suppose these languages are incomplete. Primitive

arithmetic is not incomplete, even one in which there are only the first five

numerals; and our arithmetic is not more complete. Would chess be incomplete

if we knew another game which somehow incorporated chess? It would merely be a

different game. To think otherwise is to confuse mathematics with a natural

science.”

The most striking excerpt is from page 194

“I might say that chess would never have been invented apart from the

board, figures, etc. and perhaps apart from the connection with troops in

battle. No one would have dreamed of inventing the game as played with pencil

and paper, by description of the moves, without the board and pieces. Still

the game could be played either way. It is the same with mathematics.”

It is clearly evident that Wittgenstein mentions “chess” more than just two

hundred times.

Below are excerpts from: Understanding Wittgenstein: Studies of Philosophical

Investigations. J. F. M. Hunter (1985)

For naming and describing do not stand on the same level: naming is a

preparation for description. Naming is so far not a move in the language-game

-- any more than putting a piece in its place on the board is a move in

chess. We may say: nothing has so far been done, when a thing has been

named. It has not even got a name, except in the language-game.

We can now perhaps better understand §31. Having been told about the

various pieces and how they move, without being shown a chess set, one can,

when the men are produced, ask 'Now which of these is the king?', that is,

which of these is the piece that moves one square in any direction, cannot

move into check, and so on; and one can in a different case, not yet having

had the game at all explained, but knowing something about board games, ask

'Which piece is this?', meaning something like 'Which of the roles you will be

telling me about attaches to this one?' One can understand the words 'That is

the king' without knowing any more than that if a piece has a different name

from other pieces, it will have a different role; but anyone knowing less than

that will not understand. He will not have grasped the essential point that

although (blindfold chess aside) there must be a re-identifiable physical

object, that object is not called the king on account of its physical

properties, but on account of its role in the game. (That needs some

qualification: it is good practice to design all chess sets in such a way that

players will not have to learn afresh with each set they use, which piece is

which, but it is not as if one simply could not play using a salt shaker for a

king

It is obvious that chess could be taught and played without ever naming

the pieces, and that if we were nevertheless fond of names, each player could

have his own set of them without in any way affecting the play. Some

awkwardness would arise when the game was discussed, or a player's record of

the moves was studied, but it would be a simple business to reach complete

understanding of any player's terminology. It is not so clear however what the

importance of that fact is, when we remember that it is using words, not doing

things with the objects they name, that we are trying to understand. It is not

what corresponds to managing to play chess that we are concerned with, but

what corresponds to managing to talk chess language.

There would also be intermediate cases, of which chess pieces would be a

nice example. Propositions about the role of a piece would be like statements

of the function of a knife; and there are also propositions like 'It is not a

knight if its shape does not represent a horse's head'. The latter

propositions would tend to establish the word 'knight' as the name of an

object, were it not that they are true only of certain chess sets, and were it

not that we can play chess without any object holding the knight's place, but

cannot play hockey without a puck. We could perhaps say that when playing

chess with a given full set of pieces, 'knight' is the name of an object, but

that a role is more essential to knighthood than any physical property. When

we confer knighthood on a salt shaker, we are not conferring an equine shape,

but a role.

It is not such plain sailing if we take words that have subtly different

senses. The word 'game' has a different sense in 'Olympic games' on the one

hand and 'Chess is an absorbing game' on the other; and a different sense

again in 'How about a game of chess? The difference here could not be

explained by comparing the objects referred to. How could one compare the game

of chess we played this evening with the game of chess? What objects would one

select if one wanted to compare Olympic Games with polo or hockey? Olympic

Games are not a species of game, the way board games and card games are. The

activities that go to make up board games are all games, but Olympic Games are

mostly non-games: sailing, skiing, swimming, high-jumping. That Olympic Games

are not a species of game is not a fact about the set of phenomena we call

'Olympic games', but about the use of the expression 'Olympic games'. We do

not notice on reviewing them that they possess a characteristic that we call

'being Olympic', whereas we notice on reviewing scrabble, backgammon, chess,

and snakes and ladders that they are all played on a board.

'Chess is a game' is a grammatical remark, whose primary use is in

teaching language. It does not express an opinion or an attitude, but conveys

an item of uncontroversial information about how these words are used. From it

we learn for example that if someone says he feels like a game of something,

chess is among the things we may suggest without revealing linguistic

incompetence (whereas boxing is not); but if someone says philosophy is a

game, we take him to be expressing an opinion, and in no way expect that if at

another time he says he feels like a game of something, he will accept 'How

about philosophy?' as at least a competent, if perhaps not a welcome

suggestion. He has noticed certain things about philosophy that he dislikes

and expresses by calling it a game; but one can no more notice that chess is a

game than that bachelors are unmarried.

Dr. Michael Negele writes: “I just found a curious relation between Ludwig

Wittgenstein and Emanuel Lasker. Ludwig spent 100,000 Austrian crowns just at

the beginning of WW I to support Austrian artists. Else Lasker-Schüler, who was

the only non-Austrian (and the only woman) received 4,000 crowns of these funds.

She was married from 1894 with Berthold Lasker, the brother of Emanuel (the

marriage was finally divorced in April 1903, but the couple separated already

years before) whom met her in Wuppertal (in those times, Elberfeld)”

Figure1

Else-Lasker Schueler,

received 4,000 crowns from

Ludwig Wittgenstein’s funds

and went on to become a

prominent literary figure of the

early twentieth century. She was

also a sister-in-law to World Chess

Champion, Dr. Emanuel Lasker.

For further reading:

Wittgenstein on Mind and Language. David G. Stern - author. Publisher:

Oxford University Press. Place of Publication: New York. Publication Year: 1995.

Wittgenstein, Mind, and Meaning: Toward a Social Conception of Mind.

Meredith Williams - author. Publisher: Routledge. Place of Publication: London.

Publication Year: 1999.

Wittgenstein: Connections and Controversies. P. M. S. Hacker - author.

Publisher: Clarendon Press. Place of Publication: Oxford. Publication Year:

2001.

The Voices of Wittgenstein: The Vienna Circle Ludwig Wittgenstein and

Friedrich Waismann. Friedrich Waismann - author, Ludwig Wittgenstein -

author. Publisher: Routledge. Place of Publication: London. Publication Year:

2003.

Recommended links

Ludwig Wittgenstein -

http://www.sbg.ac.at/phs/alws/alws.htm

Else-Lasker Schueler -

http://www.els.gesellschaft.wtal.de/

Emanuel Lasker -

http://www.lasker-gesellschaft.de/index.html

|