|

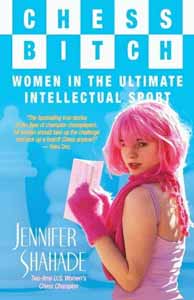

chess bitch

by Jennifer Shahade

Siles Press, Ca. Sept. 2005

|

In the

spirit of full-disclosure I feel I should mention two things

before proceeding with this review:

One, is the fact that she and I exchanged a few emails prior to the

book's release that originated after the author stumbled onto my

Lisa Lane page and wrote me on July, 27, 2004:

"Great job on your reports on Lisa Lane. I have written a section on her in

my book on women in chess (coming out this winter) and chanced by your story

when fact-checking some info on Sonja Graf. I also think that the history of

American women's chess is rich and am glad you are exploring it on your

web-page, which I will become a regular visitor to!" After such an

introduction, I was predisposed to not just to buy, but to like her book.

Second, is that the book I do have is an "uncorrected review

galley" - a white, soft-covered draft version in which the photos are of low

quality and in which there are many typos, errors and omissions. A good

friend of mine has a finished version and helped me compare the differences

(via email).You can buy Chess Bitch at

Amazon

You can visit Jennifer Shahade's

Website

You can see her entry at

Wikipedia |

Prologue:

While a prologue to a book review might seem a bit pretentious, I

wanted to express a few thoughts that don't fit into a book review proper.

Before even reading this book, I had determined to review it, something

I've never done. I had read other reviews and

commentaries and was struck by the extremes into which each of these leaped.

There was very little middle-ground.

From a sampling of reviews at Amazon one can see that....

Much of the hoopla was about the title, or

at least about the word "Bitch" which is in the title:

"Chess Bitch is

a very offensive title....I definitely will not let my children read this

book."

"I think this title is not a good

example for young players especially young female players."

Some was about its feminist leanings:

"the feminist identity politics and girlish materialistic

hype doesn't belong in chess. "

Some about Shahade's perceived motives:

"I see the personal jealousy and hatred coming out through

the author's words. The author

gave bogus opinions about her close friends such as Krush, Vicary and

especially Kosteniuk."

Some were good:

"...she isn't afraid to pull any punches. I don't

think she has set out to demean or defame anyone. She tries to tell it as

"she sees it" - how could anyone be asked to do better. Some writers try

to be over complimentary, but this wouldn't fit in will with the entire

objective of the book. "

"In "Chess Bitch" you will find a dynamic and

authoritative masterpiece on the inner world of women's chess as seen

through the eyes of one the to top women players in the United States."

Reviews from other sources were generally more balanced. For instance

City Paper

writes:

"...Shahade's manifesto for chess queens remains a contradictory

mishmash of identification and exceptionalism, working to make these

players not just girls while maintaining a gossipy "we're all just girls"

voice. In fact, it's Shahade's gossipy voice that saves the book. Where

Chess Bitch fails as a manifesto, it succeeds as a first-person memoir of

women's competitive chess ..."

While Rebecca Tuhus-Dubrow of

Village Voice writes: "Chess Bitch also debunks theories about

menstruation-induced incompetence and the pseudo-Freudian male chess

drive."

Elites TV expresses the opinion: "Through her own personal

experiences and those of other top women players, Shahade traces the

evolution of female masters past and present who have struggled to achieve

a threshold in the upper echelons of chess, often to the outspoken

displeasure of ranking males ... 'Chess Bitch' candidly captures the often

harsh and inbred bias against women masters as a microcosm of the

perennial battle of the sexes, opening an avenue of accessibility to a

universe long unapproachable to outsiders."

Review:

Jennifer Shahade gave us a bargain by writing three books in one.

Chess Bitch is the title of her maiden book that chronicles the

relationship between women and chess on historical, cultural and personal

levels. Each one of these levels is a triumph on its own.

Historical:

Shadade gives a brief history of women's chess through the lives of

world champion women

players, from Vera Menchik to Antoaneta Stefanova. She

also briefly takes the reader through

the history of women's chess in America.

Cultural:

The author delves into some of the issues, real or

supposed, that are exclusive to women in

chess. She presents a moderate feminist viewpoint

sympathetically without alienating the reader.

Personal:

Ms. Shahade offers her own experiences and insight into

how she dealt with chess as a female

while expounding on her own philosophies and ideas.

When I initially read the book my focus was on

the historical information. Much of what Ms. Shahade presents,

particularly in the section on American players, had been totally

neglected by chess authors in the past. The biographical information on

some players is sparse, but on others is quite detailed. The glimpse into

Sonja Graf was basically a repeat of Shahade's fine New in Chess

Magazine article from July, 2004. The biographies of Women World

Champions, particularly from Menchik to Chimburdanidze, were fairly

routine and handled equally well by John Graham in his

Women in Chess: Players of the Modern Age. But the author shines

when looking at the post-Georgian champions. Her treatment of the American

players is a delight and alone worth the price of the book.

The biographies aren't limited to world champions or US

champion, but extends to many other players who are noteworthy for their

potential or for their uniqueness. The tie-that-binds is their gender more

than their talent. While I won't list them all here, the number of players

who are profiled is astonishingly large.

The author's main technique seemed to be to

introduce personalities that either followed a logical historical path or

who fit under the topic of the chapter and intersperse the biographical

information with tidbits of peripheral information as well as applicable

cultural arguments. The result was akin to walking towards some

destination, but taking time along the way to wander into some alleys or

to peek inside some dimly lit alcoves that had little to do with the journey except

to provide a more interesting trip. The main problem I found was that the

destination was never always clear in my mind, leaving me confused at times about

which was the path and which was the alley. The upside is that the journey

was enjoyable enough to be an end in itself.

Ms. Shahade, rather than being the extreme feminist

that many reviewers seemed to imply, appeared to me to be more a rational

feminist. She questioned everything from a feminist perspective without

prejudice or any hint of close-mindedness. The most obvious case in point

is her handling of Alexandra Kosteniuk. While not agreeing that any

publicity is good publicity, Shahade doesn't seem to condemn Kosteniuk's

mixing of sex and chess. If she showed her feminist teeth at all, I would

say it was most apparent in writing about Fredric Friedel, founder of

Chessbase and editor of Chessbase.com and his disingenuous sexist

attitudes. The implication to me being that Kosteniuk doesn't give up her

integrity and separates her modeling aspirations from her chess career,

while Freidel wallows in his lack of integrity and purposely integrates

chess with unrelated prurient sideshows.

Some reviewers wrote this book off as a fluff piece. I

don't know why. In

my first reading, my focus was on certain areas that interest me most. I

was able to open my mind more during my second reading and look at things

more from the author's point-of-view. I was surprised and intrigued by several

ideas Shahade introduced along the way. For example, one such idea led me

to think back to the 19th century when chess began its change

from an amateur pastime into a professional sport, a change that ignited a

remarkable improvement in the quality of play and raised the bar

significantly for its serious practitioners. Women's chess has only

improved as the motivation for improvement became evident and only to the

level that the motivation inspired. Women's chess will only rise to men's

level when women are equally motivated, the way men were back in the late

1800's. The problem lies with the lack of realization that women and men

are motivated differently.

I enjoyed her introspection which

struck me as honest as it was insightful. What some reviewers passed off

as "gossipy," I believe most readers would take to be an

exclusive insider's view. For instance, I

don't know Antoaneta Stefanova personally, so it's intriguing to learn

what someone who does know her has to say about her. Beyond the insider's

look at chess personalities, we also get a personal view into Shahade's

mind as she played for the US Women's Chess Championship and what it meant

to be a member of Susan Polgár's Olympiad Dream Team.

What is the value of a book? What makes one

book great and another one mediocre?

Chess Bitch never reaches the level of Great. As a history book, it

pales when compared to other books covering similar territories, such as

Andy Soltis' The United States Chess Championship, 1845-1996 which

covers the men's chess championship in the U. S. On a cultural

level, it doesn't live up to Richard Eales' Chess: The History of a

Game or, as a personal account, to Mikhail Tal's Life & Games of

Mikhail Tal. But Chess Bitch doesn't seem to aspire to

such select greatness. By choosing to tackle the issue of women's chess in

a manner that's both objective and subjective - sometimes personal,

sometimes journalistic, sometimes scholarly - Shahade never attains

the full effectiveness of any.

Does this mean, then, that the book is mediocre?

No, not in the least. Because Jennifer Shahade tackles topics against

which there has been little written in comparison, because much of the

subject matter has been ignored by chess writers to date, because the

book, for whatever it's failings, is highly readable and ultimately

satisfying and mostly because her writing caused me to think and

re-evaluate my own positions on certain issues, I would put it in a

class all to itself.

I noted several errors worth mentioning but not worth fretting over:

1. page 25. Vera Menchik's husband,

Rufus Henry Streatfeild Stevenson, is called "Rudolf."

2. page 144. Philidor is called "the great French

player from the 19th century."

- Philidor (1726-1795) didn't lived to see the 19th century.

3. page 154. "...Morphy had already gone mad when

he was found drowned in his bathtub

- Paul Morphy neither was "mad"

nor did he die from drowning,

4. page 238. "Soon after this the Queen's Pawn

closed and Lisa Lane disappeared from chess."

- However, the Queen's Pawn closed in 1964. Lisa Lane was the 1966 co-US

Women's Chess Champion.

|

|

Archives by Title

links

personal

Sarah's Serendipitous Chess Page

The Life and Chess of Paul Morphy

Sarah's Chess History Forum

chess - general

Chesslinks Worldwide

chess - history

Mark Week's History on the Web

Chess Journalists of America

Chess History Newsgroup

Hebrew Chess

Chess Tourn. & Match History

Super Tournaments of the Past

La grande storia degli scacchi

Bobby Fischer

Bill Wall's Chess Pages

|