|

THE CONQUEROR

By J. A. Galbreath, New Orleans,

La.

If a ballot could be taken among the chess players of the world on the

question, "Who was the greatest chess player?", there is little doubt that

the overwhelming majority would be recorded in favor of one whose name is

familiar in every quarter of the globe; the compass of whose renown is

coincident with the world-wide limits of Caïssa's domain; the immortality of

whose fame is one with the perpetuity of man's appreciation of the beauties

of the purely intellectual; Paul Morphy, that unrivaled chess genius, - who

flashed like a comet into the view of the chess world in 1857; blazed as the

one bright attraction in the firmament until the middle of the year 1859,

and then vanished.

It has truly been said that Morphy was at once the Caesar and the Napoleon

of chess. He revolutionized chess. He brought life and dash and beauty into

the game at a time when an age of dulness [sic] was about to set in and he

did this at a stroke. Then he quit forever. Only two years from the

beginning to the end. The negotiations for some modern matches have taken

that long!

The manner of Morphy's abdication of the monarchy of the chess world has

been but imperfectly understood. Happening at a time when his native land

was on the eve of an awful conflict, the event was swallowed up and lost

sight of in the prodigious kaleidoscope of the civil war, and it was not

until the paramount things brought to the front by that war had somewhat

subsided that the world got back to things of lesser magnitude and began to

inquire, "Why did Morphy abjure chess?" Several years had elapsed and the

matter had already become misty. Very few knew the particulars, and they did

not care to go into them out of deference to the wished of Morphy himself,

and therefore the question was never fully answered. Theories without number

have been given out from time to time; but all of them have been more or

less conjecture. The consideration of the matter in connection with some

facts not hitherto touched upon will, it is hoped, serve to make clearer the

motive which impelled Paul Morphy to lay down voluntarily the crown which he

had so gloriously won. The obliquity of Morphy's mind, which occurred some

years later after his absolute retirement from chess, has given currency to

the most ridiculous stories at the expense of the noble game. Scribblers for

the press who do not know anything of the game have dashed off paragraphs by

the score, warning the public against over-indulgence in chess and holding

up Morphy, its brightest exponent. as the horrible example. Even the clergy

have occasionally adverted to the subject and added its admonition against

too much devotion at Caïssa's alter.

It is really surprising how much credence has been given these purely

imaginary stories, and it is the strongest proof of how

thoroughly Morphy's extraordinary performances over the chess board had

impressed, not only chess players, but the world

at large. Morphy's obliquity was of the mildest and most harmless kind.

Once, an inquiry as to his sanity was set on foot by

one of his brother-in-law [Morphy only had one brother-in-law, sbc]; but

Morphy defended his own case before the

authorities with such consummate ability that he was released from any

restraint and was never afterwards molested.

It may be here stated authoritatively that chess had nothing to do with

Morphy's hallucinations, which were first manifested

many years after his retirement. Under similar conditions from about the

year 1870 until his death on July 10th, 1884, he

would have suffered the same dementia, even if he had never learned the

first moves at chess.

It is a fact, however, that for many years the younger members of the Morphy

relatives allowed themselves to be misled by

the false and pernicious theories advanced by the space writers in the

press, and by the clergy, who knew no more than the

scribblers, and by meaning well but ill informed friends, who read the

stories in the newspapers and retailed them to the

family. These could not conjure up any other reason for Morphy's

eccentricities except, "He played too much chess." The

truth is said to be in the bottom of a well, and these good people never

looked there for it/ The Morphy family have at last

realized the truth. They know now that among the names of immortal Americans

the name of Paul Morph is indelibly

inscribed with those of George Washington, Benjamin Franklin and the others

in various walks who have shed lustre on their

native land. They know that the intellectual game in which Morphy won

enduring fame was in no way responsible for his

misfortunes.

Morphy was a thoroughly educated and cultivated man, and moreover was in

every sense a gentleman of high delicacy and

refinement, both innate and acquired. There was much of the true Hidalgo

about him. It must be remembered that in 1857,

he was but a youth of twenty. He had been very carefully brought up and had

never come into contact with the world. He

knew absolutely nothing of the seamy side of life, its base, its sordid and

its venal side. He had spent his life up to that time in

going to school, and when he came out of this carefully nurtured youth was

very much like a girl who has been brought up in

a convent, and was ignorant of the ways of the world.

Chess to Morphy at that time was an ideal, and he treated it as a true

artist. He went into it with all his youthful ardor and

vim. "The viewless arrows of his thoughts were headed and winged with

flame." His opponent's ingenuity was appropriated

and assimilated at every conquest, and thus for a brief time he lived in an

ideal world, as it were in dreamland. He did not

know that there are mean and petty jealousies among the devotees of the

game; that there are individuals who neglect useful

occupations and everything else, and hang around the chess resorts of al

large cities to make their daily bread playing chess

with persons inferior to themselves in skill, for a quarter of a dollar a

game. Morphy did not know anything of these hawks

of the game, "undesirable citizen" in every sense of the word, as our late

strenuous Chief Executive so aptly characterizes

certain persons. When Morphy went to the tournament in New York in the year

1857, he had his first experience with mean

and petty chess jealousy. He found out for the first time that there were

persons who did not have the same lofty ideas about

the game that he had, and it was a great shock to the young gentleman. Next

year, in London and Paris, he "got up against the real thing," and the

effect on his sensitive organization may be imagined. He went to Europe for

glory. He wanted a fair contest over the board with the best of them, stakes

or no stakes. He was in that enviable state of existence so well described

by George Walker, Ease and independence, freedom from the worlds chains, how

much do these lighten up the energies and fit the combatants for mental

struggle." Morphy was not concerned about stakes, hence his match with

Harrwitz was for a nominal stake, and he actually subscribed to help defray

Professor Anderssen's traveling expenses in order that the match with the

Professor could be played in Paris. There was no stake whatsoever on the

match.

Meanwhile the world was talking so much of "Morphy the chess

player" that it got on his nerves, and he asked himself if it were really

true that he was considered one of the best hawks of the game, such a person

as described above, and for whom he had the utmost contempt? Remember, this

young man had but recently earned his diploma as a lawyer, his father was a

leading jurist of Louisiana, and chess to him was a pastime. Is it any

wonder, considering the circumstances, that the idea grew on him and finally

became an obsession, that the world regarded him as "a mere chess player and

nothing else" and he resolved to quit the game and prove to the world that

is was mistaken?

When Morphy reached this city in June, 1859, after the receptions and fetes

in his honor in New York and Boston on his return from his triumphs in

Europe, he issued a final challenge offering the odds on pawn and move to

any player in the world. Receiving no response to his challenge, he

considered that the work which he had set out to do two years previously had

been accomplished, and, deeming the time had arrived which was most fitting

to abdicate the position which he had won, he declared his career as a chess

player finally and definitely closed. He held to this with unbroken

resolution during the remainder of his life, playing only a few games with

his intimate friends, Mr. Charles A. Maurian of this city and Mr. Jules

Arnous de Rivière of Paris. The former had been his schoolmate and lifelong

friend and knew more of Morphy's hopes and aspirations than any other

person. Mr. Maurian, in his obituary of Morphy written for the chess column

of the New Orleans Times-Democrat, wrote this: "Paul Morphy was never so

passionately fond, so inordinately devoted to chess as is generally

believed. An intimate acquaintance and long observation enables us to state

this positively. His only devotion to the game, if it may be so termed, lay

in his ambition to meet and to defeat the best players and great masters of

this country and of Europe. He felt his enormous strength, and never for a

moment doubted the outcome. Indeed, before his first departure for Europe he

privately and modestly, yet with perfect confidence, predicted to us his

certain success, and, when he returned, he expressed the conviction that he

had played poorly, rashly; that none of his opponents should have done so

well as they did against him. But this one ambition satisfied, he appeared

to have lost all interest in the game."

Ever since Morphy's retirement from the chess world,

whenever a young player has developed unusual skill in any quarter of the

globe, he is spoken of as "A reincarnation of Paul Morphy" as the highest

possible compliment that can be bestowed upon the rising youth. We never

hear about the reincarnation of any other departed chess master, and it is

conclusive proof that in the estimation of the world at large Paul Morphy

was the supreme master of chess.

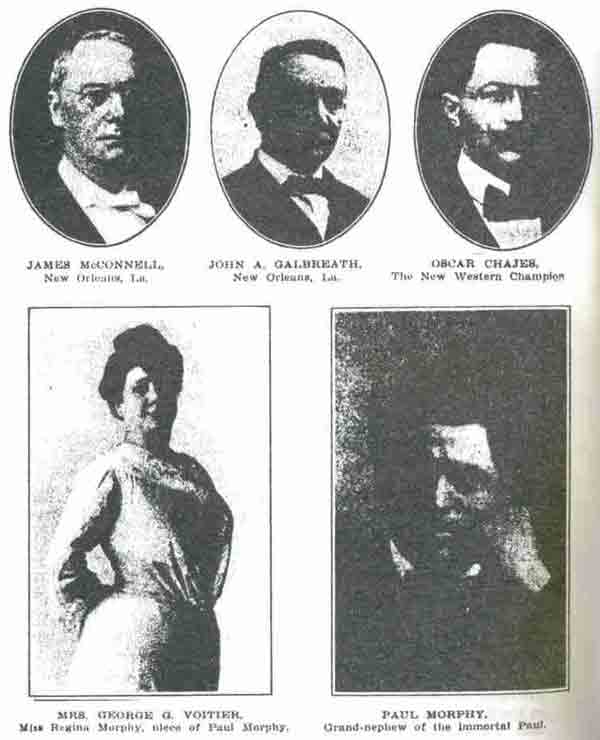

About ten years ago, the writer devised a scheme for an actual reincarnation

of the "Peerless Paul." A grand-nephew of his, named Paul Morphy, was living

in the city. He was a bright, studious lad with all the Morphy

characteristics strongly in evidence; the eyes, the hair, the complexion,

even the diffidence of his great-uncle. It would be a great thing to teach

this lad the game, carefully train him in play, and, perchance, if heredity

meant anything, at the proper moment spring a real Paul Morphy II on the

astonished and delighted chess world. It would be an actual reincarnation in

name and everything, and withal [sic]

would be such a surprise to the chess world, that the writer actually hugged

himself in anticipation of the good thing that was to happen.

The subject was broached to the lad's aunt, Miss Regina

Morphy, a niece of Paul Morphy, and who, the boy's father being dead, had

charge of him. Miss Morphy assented to the plan; but appeared not to be very

enthusiastic about it. I did not allow anything like that, however, to

interfere with the project. Young Paul was provided with a board and men and

I taught him the first moves which he learned with astonishing quickness.

Then followed a few primary lessons, and my pupil was so apt that I could

already foresee the full success of the reincarnation in the not distant

future.

Then came opposition to the plan. Anxious friends, not knowing anything of

the game or the facts about the boy's great-uncle, hearing that Paul the

second was learning to play the game and having the later years of his uncle

before his eyes, became apprehensive of the ultimate consequences, and they

hastened to lift their warning voices against his learning to play chess.

The utmost tact was used in order to discourage my plan. First one excuse,

then another, for Paul's not being on hand to take his lessons, and finally

it was stated that, as he had commenced another session at school, it would

not be possible for him to continue his chess studies. I realized that the

well meaning but ill informed friends had got in their work, and had

succeeded in persuading Miss Morphy that it would be the greatest misfortune

to allow young Paul to learn to play chess, as to do so would be to invite

his uncle's fate. I did not give up my scheme without a strong effort to

disabuse the family of its mistaken conclusions; but in vain. It seemed that

one chess player in the family, with the traditions of madness which must

inevitably overtake devotees of the game, was enough for the younger members

of the Morphy family, and I reluctantly gave up my plan for the

reincarnation.

It must be borne n mind that the younger members of the

family knew nothing, of their own knowledge, of their illustrious relative,

and that they depended upon what older friends of the dead master told them.

These in turn were misled by the fallacious stories they had read in the

newspapers, or which had been retailed by the gossips. Paul Morphy was a

recluse in his late years and even friends knew very little about him; but

the nagging tongues proved a decisive factor against my scheme as to his

grand-nephew. Miss Regina Morphy herself did not actually know much about

the matter, as her uncled died several years before that time, when she was

a small child [Regina was 15 when Paul died -

sbc]. I am glad to record

the fact that the family have at last found in truth that chess had nothing

to do with the hallucinations of Paul Morphy's late years. Paul Morphy II is

now a young man of twenty-two; just the age when his uncle retired from the

game.

Could Paul learn to play chess now> is a question which his aunt regretfully

asked the writer a few weeks ago.

She is now sorry that she allowed herself to be persuaded to oppose my plan.

Perhaps Paul Morphy, the second, may yet be an acuality in the chess world.

How he looks is shown in the accompanying picture. His is a strapping young

fellow, and quite a contrast in physique to his grand-uncle.

Mrs. George G. Voitier, (Miss Regina Morphy) the daughter of Edward Morphy,

only brother of the Immortal Paul, is a typical Creole beauty. She is one of

the Crescent City's brightest young women, and is an accomplished musician.

A short time ago, a lady in Paris, a relative of the Morphy's and a friend

of the Infanta Eulalie of Spain, wrote Mrs. Voitier that the Princess

Eulalie wished to obtain a photograph of Paul Morphy and requested Mrs.

Voitier to send her one. This turns out most fortunately for the chess

world, as Mrs. Voitier has a small photograph of her uncle taken in Paris

about the year 1867, after he had grown up to a man's estate. All the

pictures extant of Morphy represent him as the youth of 1859, when he so

completely dazzled this country and Europe. The photograph is old, faded and

badly spotted; but the photographer has succeeded in making a very good

enlargement of it. Mrs. Voitier kindly gave the writer a copy, and it is

herewith presented to the readers of the BULLETIN.

|