|

by W.R. Henry published in the ‘American Chess

Magazine’ Volume I, No. 9, February 1898

E.

B. Cook was born May 19,

1830, in New York City, in Pine Street, where the Equitable Building now

stands. His father, General William Cook, a Jerseyman by birth, a graduate of

West Point, now fills the post of Chief Engineer of the Camden and

Amboy

R.R. His mother, Ms. Martha Walker Cook, is a sister of the Hon. Robert J.

Walker, and is known to the public by a number of literary efforts, among

which we may mention a translation, from the German, of Guido Goerre’s ‘Life

of Joan of Arc’, she also translated Liszt’s ‘Life of Chopin’, and edited the

‘Continental Monthly’ for two years. The earlier portion of Eugene’s life was

spent at Bordentown, N.J., where he was placed under private tutors. Intended

by his parents for professional life, no pains were spared to give him a

thorough education. At the age of sixteen, he entered the freshman class of

Princeton College, his parents having removed to Princeton in 1844. From the

commencement, he stood but little behind students much older, and he soon

ranked first of all in his class. His previous excellent course of study, his

natural quickness and tenacity of purpose could hardly have failed to

accomplish this. His vacations were devoted not to recreation, but to the

solving of difficult mathematical questions furnished by the college records.

A Manuscript book, still in his possession, containing these questions and his

solutions, testifies to his unwearied patience, and remains in evidence of the

earliness of his passion for enigmatical things. He was seconding the efforts

of his parents only too well. Hard study and over-application induced tension

of the brain, and so much deranged his nervous system that while in the second

term of the Junior Class he became completely prostrated, and was compelled to

leave college, without hope of ever being able to resume his studies. He was

for a long time dangerously ill, and remained for several years an invalid. In

1854 his parents removed to Hoboken, N.J., where he still resides. Within a

year or two his health has improved considerably, and he is no longer the

close prisoner he once was. It was only after leaving college that Mr. Cook

paid any serious attention to chess, although he had been taught the moves by

his mother, at the early age of eleven. Now, confined to his room most of the

time, his brain surcharged with blood and thereby stimulated to unnatural

activity, the chess board furnished that which it was absolutely necessary he

should have - employment and amusement. Devoting considerable attention to the

game, he was soon able to measure his strength creditably against the

strongest players of the town. Mr. Frederic Perrin was at that time professor

of French and German at Princeton College. Games were first contested at

Knight odds, then at reduced odds, finally upon even terms, with a steady

tendency towards equality. The score of even games, played at intervals,

stood: Perrin 18; Cook, 13; drawn 3. Of the last 15 games played, each won 7

and 1 was drawn. But Mr. Cook was too nervous and physically weak to become a

player of first-class chess. He soon turned his attention to the

solution and composition of problems, and here found exhaustless

amusement, unaccompanied by the excitement and injurious effects of play. His

first published problem appeared in ‘The Albion’ for November 29, 1851. The

greater number of his early compositions were given in the ‘Illustrated London

News’ and the ‘Chess Player’s Chronicle’, Staunton ranking them among his most

valued contributions. With the commencement of its second year, he became

connected with the ‘Chess Monthly’, as amateur supervisor of its Problem

Department; and in consequence of his reputation as an analyst and critic, his

services have been frequently sought as judge in problem tournaments. In the

latter he uniformly declines to compete, preferring, as a matter of taste, to

let his productions make their appearance quietly. Amboy

R.R. His mother, Ms. Martha Walker Cook, is a sister of the Hon. Robert J.

Walker, and is known to the public by a number of literary efforts, among

which we may mention a translation, from the German, of Guido Goerre’s ‘Life

of Joan of Arc’, she also translated Liszt’s ‘Life of Chopin’, and edited the

‘Continental Monthly’ for two years. The earlier portion of Eugene’s life was

spent at Bordentown, N.J., where he was placed under private tutors. Intended

by his parents for professional life, no pains were spared to give him a

thorough education. At the age of sixteen, he entered the freshman class of

Princeton College, his parents having removed to Princeton in 1844. From the

commencement, he stood but little behind students much older, and he soon

ranked first of all in his class. His previous excellent course of study, his

natural quickness and tenacity of purpose could hardly have failed to

accomplish this. His vacations were devoted not to recreation, but to the

solving of difficult mathematical questions furnished by the college records.

A Manuscript book, still in his possession, containing these questions and his

solutions, testifies to his unwearied patience, and remains in evidence of the

earliness of his passion for enigmatical things. He was seconding the efforts

of his parents only too well. Hard study and over-application induced tension

of the brain, and so much deranged his nervous system that while in the second

term of the Junior Class he became completely prostrated, and was compelled to

leave college, without hope of ever being able to resume his studies. He was

for a long time dangerously ill, and remained for several years an invalid. In

1854 his parents removed to Hoboken, N.J., where he still resides. Within a

year or two his health has improved considerably, and he is no longer the

close prisoner he once was. It was only after leaving college that Mr. Cook

paid any serious attention to chess, although he had been taught the moves by

his mother, at the early age of eleven. Now, confined to his room most of the

time, his brain surcharged with blood and thereby stimulated to unnatural

activity, the chess board furnished that which it was absolutely necessary he

should have - employment and amusement. Devoting considerable attention to the

game, he was soon able to measure his strength creditably against the

strongest players of the town. Mr. Frederic Perrin was at that time professor

of French and German at Princeton College. Games were first contested at

Knight odds, then at reduced odds, finally upon even terms, with a steady

tendency towards equality. The score of even games, played at intervals,

stood: Perrin 18; Cook, 13; drawn 3. Of the last 15 games played, each won 7

and 1 was drawn. But Mr. Cook was too nervous and physically weak to become a

player of first-class chess. He soon turned his attention to the

solution and composition of problems, and here found exhaustless

amusement, unaccompanied by the excitement and injurious effects of play. His

first published problem appeared in ‘The Albion’ for November 29, 1851. The

greater number of his early compositions were given in the ‘Illustrated London

News’ and the ‘Chess Player’s Chronicle’, Staunton ranking them among his most

valued contributions. With the commencement of its second year, he became

connected with the ‘Chess Monthly’, as amateur supervisor of its Problem

Department; and in consequence of his reputation as an analyst and critic, his

services have been frequently sought as judge in problem tournaments. In the

latter he uniformly declines to compete, preferring, as a matter of taste, to

let his productions make their appearance quietly.

His

problems are too well known to need much characterization. Among them are some

of the most curiously ingenious positions we have. Cook’s imagination is not

as riotous as Loyd’s, but takes judgment into partnership. His conceptions are

always carefully elaborated, and have, in consequence, a chastened grace and

finish peculiarly their own.

Continuation by F.M. Teed

This ends

Mr. Henry’s sketch, with which I have taken some very slight liberties, mainly

in the shape of condensation. General Cook died in 1864, leaving his wife and

three children, each with a moderate competence; and, as for years before, Mr.

Cook has since been a seeker of health, and a student in various directions.

He received the degree of A.M. from Princeton in 1868. To quote from a recent

letter of his: “In summer I climbed mountains. I have ascended more than

230 mountains and lofty eminences. I was councillor of exploration of the

‘Appalachian Mountain Club’ in ‘83, ‘84 an ‘85.

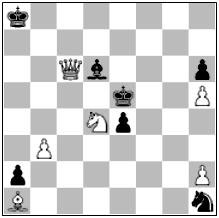

2.2

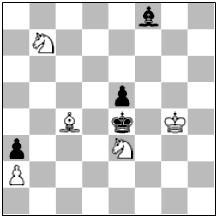

|

White to play

and mate in 3

1. Qd7

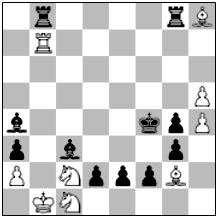

|

White to play

and mate in 4

1. Qc8 |

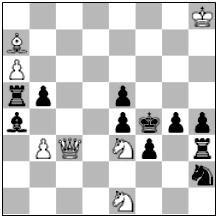

2.3

|

2.4

|

White to play

and mate in 5

1.

Qf2

|

White to play

and mate in 6

1. Nf5 |

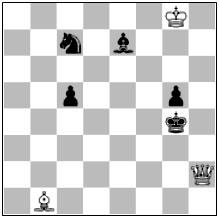

2.5

|

2.6

|

White to play

and draw

1. Nd3+ Kf5

2. Ne3+ etc.

|

Selfmate in 6

1. Nb7 d6

2. Nc5 etc. |

2.7

|

In

winter, skating seemed to offer the most enticing

exercise. The problems of balance were very attractive, and I amused myself

by creating the possibilities of single movements and of difficult

combinations. My repertoire of movements was acknowledged to be considerably

more extensive than that of any other skater. An unusual flexibility of limbs

enabled me to accomplish many feats which remained my own.” The curious

reader, who desires to emulate some of Mr. Cook’s pedestrian exploits, or to

see what can be done by a man who is neither well nor strong, may refer to ‘Apalachia’,

Vol. IV, page 54 (December ‘84), for ‘The Record of a Day’s Walk’. In that

‘Day’ (20 hours), among the Presidential Rang. White Mountains, Mr. Cook and

Dr. Sargent covered 19 miles of mountain climbing and 23 miles of rough road

walking! For many years Mr. Cook was always made chairman of the committee

appointed to prepare or revise the programmes for the figure skating

championship contests; and his skating library comprises many volumes, books

in various languages, magazine and newspaper articles, diagrams, pictures,

etc. His chess library is one of the three or four largest in this country,

embracing some unique specimens and many valuable manuscripts. He has a large

collection of music for violin and piano, the former instrument being an

especial favourite with him, and it now affords one of his chief indoor

recreations. When Mr. Henry’s sketch was written, the total number of Cook’s

problems was about 200. A recent count shows 655, comprising 154 direct-mates

in two moves, 162 in three, 71 in four, 72 in five or more, 38 wins or draws,

17 self-mates and 141 fancy, letter or conditional problems. A large number,

perhaps 100, are as yet unpublished; one of these, in five moves, appears

among the positions following. Mr Cook has been judge in many tournaments,

beginning with that of the First American Chess Congress, in 1857. Among other

important competitions in which he served may be mentioned the Fifth American

Congress, Baltimore News, Hartford Times, Columbia Chess

Chronicle, Toronto Globe and Mirror of American Sports. He

has not competed in tournaments, as already stated, preferring to have his

problems appear quietly; and moreover believing that a composer’s reputation

should be based on his work taken as a whole, and not on individual efforts,

however meritorious. Asked for an opinion on the comparative merits of

different problem ‘schools’, he said, in effect, that the

greater the variety of good kinds of problems, the better.

One is not exalted by lowering another; the merit accrues from overtopping

that other. We are not compelled to decide whether we prefer a rose to a lily,

trailing arbutus to pansies. Each may be the best of its kind, and the kinds

may be of equal worth. A study of Mr. Cook’s problems in ‘Chess Nuts’ shows

that his is indeed a catholic taste. He is equally happy in light or heavy,

playful or serious problems. Of the two-movers therein, he has indicated No

136 as his prime favourite. No. 163 is one that has been highly commended, and

No. 176 has several times received the sincere tribute of imitation. There are

many others, as well as his longer problems, deserving attention; but space

will not allow me to particularize.

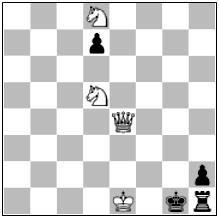

The

appended diagrams (see diagrams [2.2] - [2.7]) give a half-dozen

of Mr. Cook’s especial favourites, and solvers will find each worthy of

careful study. I must be allowed to add that, as might well be expected, Mr.

Cook is a most agreeable companion and conversationalist and a charming

correspondent. He is now, as for some nine years past, the president of the

‘Hoboken Chess and Checker Club’, and long may he continue to honor that

society by remaining at its head.

Epilogue

The

article by Teed was written in 1898 when Cook was 67 years old, Henry’s until

then unpublished sketch was written several decades earlier seeing the number

of Cook’s problems that since then had more than tripled.

Cook would

live almost 20 years more before he died shortly before his 85th

birthday in 1915. Dr. Keidanz, in the introduction of his book The Chess

Compositions of E.B. Cook of Hoboken New York 1927, informs us that many

honours were bestowed upon Cook in his lifetime. Numerous problems were

dedicated to him by his admirers and Samuel Loyd dedicated his book Chess

Strategies to him. Dr. Keidanz continues: “It is not unlikely that the

term cook which is generally used for finding a solution to a problem

not intended by its author, is traced back to our master. About this Dr.

Lasker wrote in his Chess Magazine (December, 1908-January, 1909) as follows:

“I am asked to give the derivation of the word cook, as used by chess

players. It came into use in much the same way as the word boycott did.

All the world knows that the Irish landlord Captain Boycott made himself so

disliked that everybody shunned him; hence to boycott came to mean what

it does. Mr. E. B. Cook of Hoboken, whose fame as a chess player began before

the Civil War, was, in his earlier years, so expert a solver, and found second

or more solutions to so many problems, that at last his name came to signify

the act, and ever since a problem known to have a solution not intended by its

author is said to be cooked.”

A

different explanation for the term ‘cook’ was given by the British composer

B.G. Laws in a lecture to the BCPS in 1924 consisting of his reminiscences of

nearly fifty years’ involvement in the chess problem world:

“I

often saw Horwitz about this period [around 1880] and as the question

regarding the origin of the term “Cook” was then being discussed in problem

circles, I asked him if he could throw any light on the subject. He

corroborated the statement which had been made that Kling (who had frequently

collaborated with him in end-game and problem study) would on Horwitz greeting

him with: “I have a raw idea,” ironically reply “Well, I will cook your raw

idea.” If Horwitz’s account can be relied upon, this should settle a debated

point. “

|