"On his return from his European triumphs, he entered into an engagement

with his mother never again to play for a money or other stake; never to

play a public game or a game in a public place, and never again to

encourage or countenance any publication of any sort whatever in

connection with his name."

-Charles A. Maurian, May 2, 1877

According to Regina Morphy-Voitier, Paul spend two months in Havana on his

way to Paris. He stayed at the Hotel America where his presence became known

around the

16th

of October and a committee consisting of Señors Don Blas Du Bouchet, Don

Vicente, Don Aureliano Medina and Don Felix Sicre called upon him at the hotel.

Suddenly he was besieged with private invitations and banquets in his honor. 16th

of October and a committee consisting of Señors Don Blas Du Bouchet, Don

Vicente, Don Aureliano Medina and Don Felix Sicre called upon him at the hotel.

Suddenly he was besieged with private invitations and banquets in his honor.

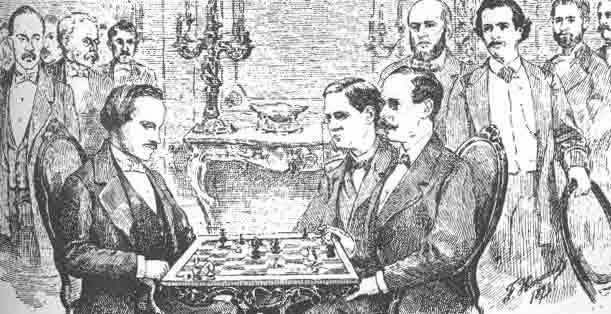

Morphy, in turn, played some games and gave some blindfold demonstrations,

mostly notably one on October 18, probably at Sicre's home. Among his opponents

in Cuba were Señors Medina, Fesser, Toscano and Sicre. He also played against J.

M. Sicre, a slave of Felix Sicre, who, as it seems, was a strong chess player.

Maurian also played a few games with their hosts.

On October 31, after attending a banquet given by Señor Eduardo Fesser at

L'Hermitage, a French Inn, Morphy and Maurian booked passage on a mail steamer

heading for Cadiz, Spain. After arriving in Cadiz, they took a train to

Paris. Not a lot is known about Morphy's stay. David Lawson claims, without

giving specifics, that in December of 1862 an "American correspondent for the

New York Times in Paris" wrote:

Since my arrival I have met with Mr. Paul Morphy, the famous chess player,

about whose doings and whereabouts such contradictory reports have been

circulating in the United States. Mr. Morphy has not been on any rebel

general's staff, nor has he taken any part in the war. He left New Orleans

long after the capture of the city by Federal forces and went to Havana,

taking passage thence to Cadiz, and reached Paris a few days ago. Kolisch, the

eminent Hungarian player is also here, and chess amateurs are making an effort

to bring about a meeting between the greatest chess genius of the world and

another star not worthy to encounter the master. Morphy, however, assures me

he has renounced chess altogether...

Of course, the chess Morphy had renounced was competitive chess. He still

played with friends and for enjoyment. He played games at the homes of

both Rivière and Doazan. Besides Morphy, Gabriel Eloy Doazan, who had played

both Deschapelles

and Bourdonnais, in a letter written later to George Allen, expressed some of his observations:

After Deschapelles

and Labourdonnais, I was lucky enough to see a young man whom one can and

whom one must place in the same bracket. His superiority is as obvious as

theirs. It is undeniable too and reveals itself in the same way.

- is Morphy as good as or better than Labourdonnais?

I was often asked this question, to which it is

impossible to answer in a simple and affirmative way. Some reflections will

help understand this impossibility. Art has several faces, and should be

examined, analysed, appreciated in various aspects by seeing things from

different points of view.

Is Raphaël a greater painter than Rubens? Another pointless and insoluble

question.

...

Let us come now to Labourdonnais and Morphy, one entering life, the other

dead, but both immortals! I do not want to compare them, I will leave

someone else the sad task of lowering one of them just to raise the other. I

only want to emphasize the strange contrast of their organizations and to

highlight the impossibility of a discussion the purpose of which would be to

demote one of them to the second rank.

...

In Labourdonnais' time, chess was still a game. A game infinitely higher

than any other, but one which excluded neither gaiety nor animation. The

loss of one or two games was suffered without irritation and was not looked

upon as a disastrous event, a major humiliation which lowered you in the

opinion of your contemporaries and of posterity while giving victory to your

enemies. These expressions are exaggerated, undoubtedly; but this expression

is founded on something real. Yes, by making efforts everywhere and

unanimously to improve the theory of chess, while trying to make it a

positive science, we changed, so to speak, the aspect of the play; and the

very character of the players was appreciably modified.

When Morphy doesn't play a move for twenty minutes, he

analyses the positions, calculates all the variants and their consequences

until their last limits, without the least apparent effort; his face remains

calm, blood does not rise to his forehead. It is an incomparable power of

abstraction and a clearness of intuition that one cannot admire too much. So

like all real chess-lovers, I just watch, wait and admire. But, not far

away, there are players of fourth or fifth force who make us just as long

for a bad move. This systematic slowness is the wound of our time. Ancient

times were less serious: Allow me to miss them for some reasons.

These general considerations will help us understand

better what I have to say about these two famous players. We know Morphy,

his distinction, his reserve, his sobriety, the delicacy of this young body

which supports a head so admirably formed; moreover, the bust by Lequesne

and his photo and engraving reproductions have made his features familiar to

all, so to speak, popularized them. The features of Labourdonnais are

unknown to the majority of current players. For me, who lived with him, they

become uncertain as time goes on and our memories weaken. Instead of a

portrait, we only have a sad caricature drawn from a dreadful mask molded

after death.

Morphy's mother,Thelcide, and his

sister, Helena, had arrived in Paris long before Paul. They were visiting

his other sister, Malvina, who had moved there a few years before - though

her husband, John Sybrandt, spent most of his time in the United States

conducting his business. In Paris Morphy met with his family but led a life

apart from them.

Ignatz Kolisch

Learning that Morphy was in Paris,

Ignatz Kolisch

took the opportunity to challenge him to a match.

On February 14, 1863, (published in La Nouvelle Regénce in March 1863)

Kolisch wrote to Morphy:

Sir:

The distinguished reputation you have acquired at chess

has long since excited in me an ambition - presumptuous perhaps, but very ardent

- to have the honor of encountering you at that game. You will remember that two

years since my friends endeavored to bring us together and transmitted you a

proposal, to which you replied by a promise equivalent to a formal engagement in

case you should ever return to Europe - a promise which was made public in the

American journal, Wilkes' Spirit of the Times, and which has been

registered in La Nouvelle Regénce. On the faith of this engagement I left

England when I heard of your arrival in Paris to put myself at your disposal.

Knowing, however, that at the beginning of your visit private considerations

withheld you from playing chess, I abstained from communicating my resolution.

But now, Sir, that you have resumed a recreation in which you so much excell

[sic], and daily play the game with various adversaries,

the time appears to arrive when I can recall to you your former promise.

I am sure, Sir, that I shall not appeal to your

courtesy in vain; and I believe you will think it reasonable that I should

exercise the same liberty which you used when you first came and threw down the

gauntlet to the chief players of Europe.

Justified by both your promise and your example, I have

the honor to propose to you a chess match. The conditions, if you please, shall

be the same as those first proposed to you in the letter of the secretary of the

St. George's Club - namely, that whichever of us wins the first eleven games

shall be pronounced the conqueror.

Awaiting your reply, I beg you to accept the assurance

of my consideration, &C.

Ignatz Kolisch

In response to this seemingly reasonable challenge, Morphy apparently sent to

Kolisch (and to La Regénce) a note, declining the offer to play,

explaining his desire to divorce himself from competitive chess. In addition,

Morphy sent a note to La Regénce, asking them to publish this

additional statement:

"I could have believed at the time when hearing of your successes that you

are superior to other players I had encountered in Europe, but since, as you are

well aware, the result of your matches with Messrs. Anderssen and Paulsen had

not been favorable to you, there is now no reason why I should make an exception

in your case, having decided not again to engage in such matches, an

infringement of my rules which I should be obliged to extend to others, &C, &C.

Paul Morphy

Morphy further indicated his resolve to abandon competitive chess in his

letter to Willard Fiske dated February 4, 1863. It was ostensibly a reply to

Fiske concerning an invitation to Morphy by the Vienna Chess Club:

My dear Fiske,

Pray, do not be too prompt in condemning the tardiness

of my reply, for in this case at least, it can be justified. I have purposely

abstained from returning an immediate answer to your favor, in the hope of being

enabled to take a trip to Vienna, not for the sake of chess-playing, but

activated by the very natural desire to see you after such a lapse of time as

has gone by since my last visit to New York, and inquire about old friends and

associations made doubly dear by the sad events that are transpiring in our

distracted America. Much as I would enjoy a visit to Germany for those and other

reasons, I am sorry to say that it will not be in my power to leave Paris at

present. I am here with my brother in law and part of my family, the remainder

being in New Orleans. We are all following with intense anxiety the fortunes of

the tremendous conflict now raging beyond the Atlantic, for upon the issue

depends our all in life. Under such circumstances you will readily understand

that I should feel little disposed to engage in the objectless strife of the

chess board. Besides, you will remember that as far back as two years ago I

stated to you in New York my firm determination to abandon chess altogether. I

am more strongly confirmed than ever in the belief that the time devoted to

chess is literally frittered away. It is, to be sure, a most exhilarating sport,

but it is only a sport; and it is not to be wondered at that such as have been

passionately addicted to the charming pastime should one day ask themselves

whether sober reason does not advise its utter dereliction. I have, for my own

part, resolved not to be moved from my purpose of not engaging in chess

hereafter. The few games that I have played here have been altogether private

and sans facon.

I never patronize the Café de la Regénce; it is a low,

and, to borrow a Gallicism, ill frequented establishment.

Hoping that you will excuse my dilatoriness, and

wishing you health and happiness,

I remain Yours truly,

Paul Morphy

P.S. Sybrandt begs to be kindly remembered to you.

During Morphy's first trip to Europe, Prince Sergei Urusoff, one of Russian

master Alexander Petroff's frequent opponents, had written a letter to

Morphy inviting him to Russia to play a match with Petroff. Morphy, of course,

couldn't make such a a trip and the match never occurred. During Morphy's second

visit to Paris, Petroff was living in Warsaw and came to Paris with his

daughters to visit a health spa. He was very aware of Morphy's presence.

Petroff, born in 1794, was considerably older than Morphy and had retired from

active chess but he still greatly desired to play the famous American. Morphy,

also retired from chess, met with Petroff on two occasions.

Urusoff had described Petroff as: "tireless, and that is a great

virtue; he is not nervous like Harrwitz and does not yawn like Anderssen He is

like Morphy in everything but has an advantage over him in years."

Alexander Petroff

Marginal notes found in Petroff's 1859 and 1860 issues of Shakmatny Listok

indicate that Petroff had studied and analyzed many of Morphy's games.

Particularly notated were Morphy's handling of the four Philidor Defenses

employed by Harrwitz during their match.

Petroff was quoted, in the Shakmatny Listok as saying: "As far

as a match with Morphy is concerned, why not play? I'm ready to play whenever

they will back me... I don't regard myself as Morphy's equal in strength."

The chess world was ready for a confrontation between these two living

legends:

"We have heard about the coming encounter between Morphy and Petroff. This

will truly be one of the most remarkable battles which has ever taken place.

This will be a splendid day for chess."

- La Nouvelle Regénce, July 1863

"One of the oldest and most accomplished masters, Mr. Petroff (now 69 years

old), has lately enlivened the Chess circles of Paris by his presence. His stay,

for the moment, was a brief one but he intends, it is said, to return to the

French capitol in a few weeks and make it his home for the winter. Should he do

so, the expectations are entertained that Mr. Morphy, who is still in Paris,

will be tempted to break a lance with the Nestor of Russian chess. In that case

we may anticipate the pleasure of recording some of the finest games which have

been played since the great combats of twenty or five and twenty years ago.

During his recent sojourn in Paris, Mr. Petroff was a frequent visitor to the

Café de le Regénce (and played with Journaud and others).

-Howard Staunton in the Illustrated London News, November 7, 1863

However, a match wasn't to take place. Petroff wrote to Mikhailov, the editor

of Shakmatny Listok: "I've visited Morphy twice, and he has

visited me. Doazan has told me that he has absolutely given up the game."

While no games between the two have been recorded, they did meet on several

occasions. It seems that Morphy met with other Russians besides Petroff. He is

thought to have made the acquaintance of the Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev

(1818-1883) and while they may not have met, Leo Tolstoy, who was in London in

1861, is known to have purchased, while there, a book on Morphy for his personal

library.

In the end of January 1864, Morphy left for New Orleans to see what

could be salvaged from the results of the Civil War and Northern occupation.

Arriving in Santigo de Cuba and then making his way the 540 miles north-west

to Havana on the steamship, Aguila, on February 16, Morphy only spent two days

on the island despite his warm welcome.

The rich banker, Mr. Francisco Fesser, gave a sumptuous banquet on Tuesday in

honor of the celebrated chess player Mr. Morphy who should be leaving today for

New Orleans. aturally the greater part of the invited guests were enthusiasts of

the noble game in which Mr. Morphy recognizes no rival, but this was no reason

why we could not count many and very beautiful ladies of our high society.

Before dinner he played a game with Mr. Sicre, giving him a knight. Later he

played alternately several games with Messrs. Dominguez, Golmayo, and Sicre, by

memory, while carrying on at the same time an animated conversation with the

estimable family of Mr. Fesser. On all the games he came out the winner,

being applauded each time his fatigued opponents gave up their games and asked

for grace... Among the invited guests we could count Messrs. Villergas, Golmayo,

Sicre, Dominguez and Palmer, very well known for their affection for the

difficult game, and the Messrs. Valdes, Cespedes, La Calle, Diaz, Albertini and

others.

-the Havana El Tiempo, February 18, 1864

Morphy played Celso Golmayo five games at Knight odds, winning two, losing

three. El Moro Muza repoted that:

Mr. Morphy having played several games with Señor Golmayo, to whom he gave a

Knight, has come to confess frankly that Señor Golmayo is too strong to receive

a Knight from him and that the most he could give him would be a Pawn and two

moves, a declaration that places Señor Golmayo at the very highest level amongst

chess players.

In return, Goyomayo, in the April 1888 issue of the Charleston Chess

Chronicle wrote:

In my many games with Morphy at odd of a Knight, I became hopelessly

bewildered by the brilliancy and the intricacy of his combinations, but when I

sit down with Steinitz on even terms I feel as though I have a very respectable

chance to win.

Morphy arrived in New Orleans the last week of February at which time

he tried to establish himself in his profession.

David Lawson is adamant that it was after his return from Paris in 1864 that

Morphy first attempted to open a law office on 12 Exchange Street.

It only survived a few months.

Elsewhere [e.g. p.26, Morphy Gleanings] it is stated

erroneously that he opened a law office soon after his return in

1859, but this was his first time to establish himself at

his profession.

After the end of the war, Morphy decided to go to New York to attempt to

discuss the possible publication of a book of his games which he would annotate.

He left for New York around July 25 and met with Daniel Fiske and Napoleon

Marache. Marache and Charles A. Gilberg aided Morphy in trying to amass the

texts of his games from a variety of sources (his uncle Ernest wrote to the

editor of La Stratégie on March 14 that Paul was in New York working on

some of the proofs to a four volume collection of his games to be published by

Appleton). They worked on the project for several weeks but with financing tight

after the war, a book had to have more than speculative value. The book of

the Fifth American Chess Congress explains that the project fell through because

they couldn't come to financial terms. According to Gustavus Charles Reichhelm

[president of the Philadelphia Chess Club as well as a chess editor and an

historian of chess in Philadelphia], Morphy had applied to him for the scores of

some games he played in Philadelphia and that he learned that the project ended

because Morphy refused to play any new games which might make the book more

salable and worth investing in.

Returning to New Orleans in the beginning of November, the New Orleans chess

club revitalized itself and on November 14, 1865 elected Paul Morphy as it's

president with Charles Maurian as secretary. Morphy is known to have played a

four board blindfold simul of which the score of only one game, against Paul

Capdevielle, has survived.

Little is known about Morphy's legal activities. Other than his chess games

with Charles Maurian, little is known about Morphy's activities for the next two

years. Whitelaw Reid, an author who was in the South gathering material

for his book, "After the War: A Southern Tour," met Morphy at a soirée at

the home of Christian Roselius, Dean of Faculty at the University of Louisiana

and a Professor of Civil Law. After commenting on the abundance of fine spirits

and wines and the general absence of ladies at these soirées, Reid described

meeting a "modest-looking little gentleman of retiring manners with

apparently little to say; though the keen eyes and well-shaped head sufficiently

showed the silence to be no mask for the poverty of intellect." He then

interjected his opinion that Morphy was "the foremost chess-player of the

world, now a lawyer, but, alas! by no means the foremost lawyer in his native

city."

Born near Xenia, Ohio on Oct. 27, 1837, Whitelaw Reid became a war

correspondent for the Cincinnati Gazette, served as served as

aide-de-camp to General William S. Rosecrans and was present at both Shiloh and

Gettysburg. After the war he took up cotton-planting in Louisiana for a while

resulting in After the War. Horace Greeley hired him to work for the New

York Tribune . When Greeley died in 1872, Reid took his place as editor,

printer and circulation manager. In 1881, Reid married

Elizabeth Mills, the daughter of Darius Ogden Mills, a California

millionaire. In 1892 he ran as the Vice Presidential candidate with Benjamin

Harrison. He also wrote: Ohio in the War - 2 vols., 1868; Schools

of Journalism, 1871; The Scholar in Politie 1873; Some

Newspaper Tendencies, 1879; and Town-Hall Suggestions, 1881.

He died Dec. 15, 1912.

Whitelaw Reid

Christian Roselius was born on Aug. 10, 1803 near Breman, Germany. In 1819 he

emigrated to New Orleans. First he became a successful lawyers, then from

1841-1843, he was appointed Louisiana State Attorney General. In 1857 he was

named Chief Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court. The last 20 years of his

life were spent as Dean of Faculty and professor of Civil Law at the University

of Louisiana. A well read man, he possessed on of the largest private libraries

in the South and was known as a congenial and generous entertainer whose soirées

were well known and well attended. He died Sept. 5, 1873.

Christian Roselius

In July of 1867, Morphy accompanied his mother and sister, Helena, to Paris

where they spent the next 15 months. That same month in the Grand Cercle, 10

boulevard Montmartre, The Grand Tournament of Paris was taking place in

conjunction with the Exposition Universelle, the Paris International

Exhibition. Although the tournament started in June and concluded in July, it was

rumored that Morphy might enter it. Nothing could have been less likely.

Morphy wasn't interested in playing chess at all in Paris. (The prize-winners in

order were: Kolisch , Winawer, Steinitz, Neumann, De Vère and De Rivière).

Morphy spent time at the home of Arnous de Rivière and associated with Gustav

Neumann and Eugene Lequesne, but seemed to have never played a single game of

chess.

Sergeant relates W. J. A. Fuller's account of of

running into Arnous de Rivière at the Café de la Régence in the summer of 1885.

De Rivière told Fuller that Morphy had pawned his watch while engaged in some

expensive legal matters (referring here to p.73 concerning Morphy's suit against

his brother-in-law John Darius Sybrant, the administrator of Alonzo's estate)

and that Rivière had "loaned Morphy a large sum of upon it" and that "the

pledge was never redeemed."

Adding some substantiation to Fuller's account,

Sergeant continues by relating how that Augustus Mongredien's son, A. W.

Mondgredien, saw the watch in Paris, 1921, at which time he could have bought it

for 6,000 francs from the heirs of Arnous de Rivière.

Lawson adds (p.292) that "His present

circumstances suggested to him that his brother-in-law Sybrandt, the

administrator of his father's estate, had defrauded him or mismanaged the estate

and so Morphy started an absurd lawsuit against him which came to nothing - he

had probably spent most of his available patrimony before his second trip to

Europe, one reason why he had taken a large loan on his watch while there."

According to Lawson, Sheriff W. C. Spens wrote in the Glasgow Weekly

Herald, July 19, 1884 - which would be 17 years later -

Morphy returned to Paris, where he had a married sister living. Events had

proved disastrous to his parents [the Civil War] and also blighted his own

prospects, which had such a depressing influence on his over-wrought mind, that

it perfectly paralyzed his energies. He lost his taste for chess entirely.and

Neumann told us in 1867 that he could never prevail upon Morphy to play a game.

They frequently met at De Riviere's house, and Morphy would occasionally

condescend to look at some variations, when the Paris congress book was being

prepared for press. We recollect his coming once as far as the door of the

Régence to make some inquiries, but he would not enter, in spite of M.

Lequesne's entreaties.

According to Edward Winters' Chess Note #4053, entitled The Pride and

Sorrow of Chess: "On page 113 of the April 1885 International Chess Magazine

Steinitz wrote:

‘... the fearful misfortune which ultimately befell “the pride and sorrow of

chess”, as Sheriff Spens justly calls Morphy, can only evoke the warmest

sympathy in every human breast.’

Sheriff Walter Cook Spens (Feb.1, 1842 - July 13, 1900) was a leading

Scottish player and one of the founders of the Scottish Chess Association

in 1884.

His tournament achievements include:

10th Dundee, 1867; 11th Glasgow, 1875;13th Cheltenham, 1876;

10th Manchester, 1882; 6th-8th Birmingham, 1883; 3rd Glasgow, 1884; 7th

Edinburgh, 1885;

9th-10th Glasgow, 1886; 7th Edinburgh, 1887; 6th-7th Glasgow, 1888;

3rd-4th Edinburgh, 1889;

1st-2nd Dundee, 1890; 8th-9th Manchester, 1890; 3rd Glasgow, 1891; 6th

Edinburgh, 1892;

1st Glasgow, 1893; 3rd-4th Edinburgh, 1895; 4 Dundee, 1896; 4th-5th Stirling,

1899; 5th Dundee, 1900

Sheriff Walter Cook Spens

According to the chess column in the Scotsman newpaper, "The Spens Cup

was donated by Sheriff Walter C Spens, the founder of the SCA, in 1901. The

current trophy is a 1946 replacement after the original was destroyed during the

Second World War."

"Sheriff Spens is alleged to have won the shortest ever game in the

Scottish Championships, "about 1893". 1 e4 d5 2 exd5 Qxd5 3 Nb3 - White was

distracted while in conversation and intended Nc3. Since Nb3 is illegal the

rules of the time required a king move be played, so 3 Ke2 Qe4 mate! This

story is recounted in the British Chess Magazine of January 1932 by six-time

Scottish champion, Dr.Ronald MacDonald, but there is some doubt as

to its veracity. The Graham Burgess book The Quickest Chess Victories of all

Time does not mention Spens but gives the same moves in an 1893 (!) game

Lindemann-Echtermayer, from Kiel, Germany."

Morphy returned to America arriving in New York in September, 1868, where he

stayed at the New York Hotel (and avoided the New York Chess Club) a few days

before returning to New Orleans where his life became as hidden as it was (most

likely) simple and monotonous.

Between 1868-9 Morphy and Charles Maurian played 4 series of games at Knight

odds.

Series 1 - Morphy 6, Maurian 3, Drawn 2

Series 2 - Morphy 3, Maurian 3

Series 3 - Morphy 7, Maurian 10

Series 4 - Morphy 0, Maurian 4, Drawn 1

After the last series, played in December 1869, Morphy informed Maurian that

he was now too strong to receive Knight's odds and thenceforth he would only

receive the odd of Pawn and two.

According to Sergeant's Morphy Gleanings

In the biography of Morphy in the Book of the Fifth American Congress

it is stated that he retained his interest in chess, after ceasing to play, to

the extent of analyzing and solving problems. He did not compose. Judge L. L.

Labatt, of New Orleans, relates that Morphy, after he had given up practical

chess, could read down the score of a game and get the entire game in his mind.

He could then point out the weak moves in the loser's game and would say he

could beat "any of these fellows."

According to Lawson

March 15, 1873 "...a letter from Charles J. Woodbury to the Hartford

Times disclosed that Morphy still played chess, but only on special

occasions and in privacy, although this time it was a "numerous" privacy, so to

speak. Woodbury's interview letter is for the most part taken up with the story

of and comments on Morphy's life. Morphy greeted him in French and Woodbury

replied in the same, and knowing something of the family circumstances may have

mentioned that chess could do a lot for him. As Woodbury reveals, if there was

one thing that enraged Morphy it was constant talk of chess with strangers and

the suggestion that he use his skills at the game for profit:

A flight of stairs leads the way up to the

dwelling-rooms. I had never seen Paul Morphy, but I knew him the moment he stood

quietly before me, simply dressed, slight, smooth and melancholy-faced, with a

head and brow over-hanging with their own weight. So full of dignity, so empty

of self-consciousness, was his presence, that I was almost prepared by it for

the quick answer he made me that he was but an amateur, and was adverse to

notoriety. But the passion of the Creole eyes overspoke the tutored voice at a

remark I made about the contrast between what he said and what he had done. My

imperfect French added to the embarrassment of the moment, and his thin

self-control gave way to one of those paroxysms of passion to which I have since

learned he is constantly subject. Happily, the coming of his mother soon

divested him of the strange suspicion that I thought him to be a professional

gambler; and, afterwards, through Mons. C. A. Maurian, an intimate friend and

the best public player in New Orleans, all of these misunderstandings were

removed...

Once in a while, the solitary athlete can be induced to

show that his power is only in abeyance. I saw him at a private séance, just

before I left, beat simultaneously, in just 2¾ hours, sixteen of the most

accomplished amateurs in New Orleans. His strength had never been fully tested,

and will probably never be fully developed.

Paul Morphy is poor. Unlike a Yankee, he finds it

impossible to live on his talent. Opportunities there are in abundance, - rich

offers for public exhibitions of himself as delicate as those grasped at by men

who would pretend to more honor. He steadfastly refuses them. He was morbidly

sensitive to misjudgment, lest he be taken for one who "travels on his muscle,"

and on all his journeys, defrayed his own expenses, and always played in the

presence only of select companies, to which no money could gain access. There

seems to me to be a certain attraction in this fine delicacy, which one would

encounter not elsewhere among us than in the half-foreign society of New

Orleans, amid which Mr. Morphy was reared. It is dearer to than wealth or

renown, or the strange gift by which he must get his daily bread or go without

it. Some there are who do not live by bread alone."

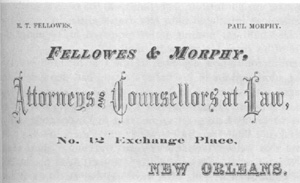

From about 1872 to 1874 Paul Morphy partnered with established attorney E.

T. Fellows. Most information about this venture is speculation. Morphy's

aversion to discussing chess would have made any public profession difficult at

best. The extent of his involvement in this firm is unknown.

In a letter to the New York Sun, May 2, 1877,

Charles A .Maurian explained:

[Morphy] is now practicing law in this city, and has never been

insane, or spoken of in that relation by his family or friends. As to chess, he

is unquestionably to-day the best player in the world, although he does not play

often enough to keep himself in thorough practice. He gives odds of a knight to

our strongest players, and is seldom beaten, perhaps never when he cares to win.

This demonstrates that Paul was doing some sort of legal work

and playing chess as late as 1877.

Paul Morphy's brother, Edward married Alice Percy and together they had two

children, Edward (1862) and Regina (1870). Regina Morphy, who was 14 when Paul

Morphy died (1884), married George Gastien Voitier. In 1926 Regina

Morphy-Voitier wrote about her famous uncle from her reminiscences, from family

papers and other research as well as from her connections with people who had

known Paul.

Her finished product was a 40 page paper-covered,

privately-published pamphlet, entitled, "Life of Paul Morphy in the Vieux

Carré of New-Orleans and Abroad"

From this pamphlet we learn something of Paul Morphy's life after

chess

"Paul Morphy was exceedingly fond of

grand opera and very seldom missed a performance at the old French Opera House

on Bourbon Street..."

We learn he liked to walk along Canal St. carrying a cane and

sporting a monocle, admiring the ladies. He generally attended daily Mass at

the St. Louis Cathedral after which he'd continue his stroll, perhaps buying

flowers or "calas" (rice cakes) or cakes from Himbert's "charcuterie

shop."

" ... He was exceedingly fond of tea...He never ate much lunch but invariably helped himself to two cups of tea and

several pieces of buttered toast."

" ... Paul Morphy was exceedingly charitable,

and old age and childhood strongly appealed to him. He was never known to

refuse alms to worthy mendicants."

Morphy Madness |