What makes this village somewhat peculiar, somewhat different than anyplace else in the world, is its deep and time-honored chess tradition. This tradition isn't merely a show, but more a way of life for the 1200 villagers. The town itself is known as Schachdorf Ströbeck, or Ströbeck, the Chess Village. The story begins almost 1000 years ago, but the tradition is a mere 180 years old. The Hatz Mountains remained uninhabited until almost 1000 AD. Ströbeck itself was built around 995 AD when Otto II donated some land to the monastery in Drübeck. Later Heinrich II donated a piece of land known as Ströbcke to the Quedlinburg Foundation. In 1268 Ströbeck became the property of the bishopric of Halberstadt and became part of the medieval trade route. In the year 1011, a Slavic nobleman by the name of Duke Gruncelin who was Wendish (The Wends was a tribe Slavic people who lived in Spreewald, a region northeast of Dresden and southeast of Berlin - another story mentions Prince Kunzelin of Meissen.) placed under arrest in the stone tower of Ströbeck by order of Heinrich II of Germany. He was an educated man and the prison life was a boring existence. To pass the time (and legend has it, to earn his freedom) he fashioned a crude board with chaulk and pieces he whittled from wood and taught his guards a game that he used to play at court called Schach. Of course it was a medieval version of the game whose rules differed from today's game of chess. Still, the game, which at that time was reserved for royalty and clerics, caught on as the guards taught it to their friends and family. The entire town seemed to enjoy the game and even taught it to travelers passing through. The village gained a certain measure of renown which didn't go unnoticed by the rulers who exempted the village from certain taxes on the condition that they maintain and pass down through generations their willingness to always offer travelers a game of chess. Many traditions developed over the course of time.  Since at least 1688, the people of Schachdorf Ströbeck have been putting on live chess games. They even performed at Leipzig during the 1960 Chess Olympics. There's a chess tournament held every year in Ströbeck usually supplemented with pageantry and a live game. The chessmen are school children who, over the years, work their way up from mere pawns to pieces, minor and major, even to king and queen.

Another quaint custom began the same year when the Ströbeckers sent a delegation to Duke Ludwig Rudolf of Braunschweig who liked to hold festivities during which the peasant could be married. The delegation made the unusual request that chess should play a part in their own festivities. According to Ströbeck's official site: The duke and duchess sent for the old village mayor, Söllig, and his eight-year-old son Valentin and invited them to play chess. The boy watched the game between the two men closely and when his father was about to make an imprudent move, he tipped him on the shoulder and called out Vadder mit Rat!, as was the custom in Ströbeck, urging him to think again. The village mayor reconsidered the move, eventually decided on a better one and went on to win the game. Afterwards the boy explained to the duke, displaying a profound understanding of the game, what the negative consequences of his father's intended move would have been. The boy thus won favour with the duke who made him his protégé and financed his studies. After the death of the duke in 1738, Valentin Söllig first became court deacon and then preacher in Hasselfelde in 1749.This precluded the present marriage law: In the 17th century a custom arose in Ströbeck that the groom had to play for his bride, i.e. the groom had to play a game of chess against a selected player, usually the village mayor. While they were playing, guests were not allowed to utter a word about the game. Only when they thought that their player was making an error they were allowed to call out: Vadder mit Rat, an invocation to play with caution and good sense. If the groom lost the game, he would have to pay a certain fine to the village treasury.Also from the official Ströbeck site: It became a custom and tradition that, on taking the throne, the new regional sovereign would be challenged by the men of Ströbeck to a game of chess on the village green. In the 17th century civil servants from the Electorate of Brandenburg would come to Ströbeck to play against the villagers for the state taxes. The villagers regularly won, and were thus exempted from paying taxes. The Great Elector was amazed that his civil servants regularly lost to the villagers. The chronicle records that on 13 May 1651 he came to Ströbeck in person and sat down with the peasants, at the chess board in an open field in accordance with the old custom. The ambition of the villagers was spurred on by this royal visit and they refused to give in even to their ruler. The game ended in favour of the villagers. In a gesture of recognition, the Elector [Prince Frederick William of Brandenburg] gave them a precious chess set which can be seen today in the museum [The board measures 12 by 8 squares, and features the addition of three pieces: the sage, the jester, and the courier - this is commonly referred to as Courier Chess]. The coat of arms of the Electorate of Brandenburg inlaid in the centre of the frame bears the following inscription:It is hereby confirmed and recorded for all time that on this day of 13 May 1651, His Majesty the Elector of Brandenburg and Prince of Halberstadt, Friedrich Wilhelm, has, in his mercy, given this chess and courier set to the little village of Ströbeck, and has promised to protect the village in accordance with the long tradition. The wedding custom dictates that the bridegroom must play the mayor or some designated official in a game of chess. If the prospective husband wins, he is exempt from certain wedding fees.  In 1823 when Germany, as well as other parts of Europe, were building public schools, the Ströbeck school asked that a certain amount of money be set aside to provide awards of

chessboards and chessmen to the winners of the end-of-year tournament. In 1823 when Germany, as well as other parts of Europe, were building public schools, the Ströbeck school asked that a certain amount of money be set aside to provide awards of

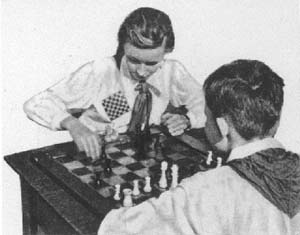

chessboards and chessmen to the winners of the end-of-year tournament. This is also the year that chess education became compulsory. Children carry their chessboards with them to school along with their bookbags and lunchbags. The children today receive an hour of required chess each week, but more would certainly not be frowned upon.  The Schachdorf Ströbeck insignia is a chessboard and is portrayed in their coat-of-arms. The symbolic chessboard is almost omnipresent in the small village. Houses display the symbol as well as many of the prominent buildings. Even the village square, the Platz zum Schachspiel is dominated by a large, paved chessboard in its center.

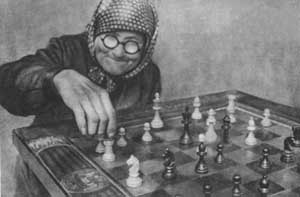

The chessboard is even featured on the flag that flies on the church spire as well as on the flag that flies from the Chess Tower or Schachturm along with the date: 1011.  The traditional Ströbeck tavern is located on the village square. The Gasthaus zum Schachspiel is centuries old and it is still at the same location. The picture on the left shows the tavern in the background.  Students wear chessboard badges on their uniforms.  The game is played and enjoyed by young and old alike.

The name of the local schools are Dr. Emanuel Lasker Primary and Dr. Emanuel Lasker Secondary.

When Harriet Geithmann's wrote her article, Ströbeck Home of Chess, for the May 1931 issue of The National Geographic Magazine, she brought international attention to this quiet village. She never envisioned a time when the charming traditions these people hold so dear would ever end. But an end does seem to be a distinct possibility. Ironically, the danger lies from within. Authorities in regional government of Saxony-Anhalt have informed the Dr. Emanuel Lasker Secondary School that it will have to close since the enrollment there has fallen below the legal minimum 40 pupils.  Jan-Hendrik Olbertz, the regional Education Minister, claims, "There are a number of other schools in the vicinity of Ströbeck." and that he saw no reason why Ströbeck's school should be kept open. The villagers aren't taking the decision lightly. Susanne Heizmann, who is a spokesperson for the school's parents' council, countered, "People here love chess, and our school continues the proud traditions of the chess village of Strobeck. If the school goes under then almost two centuries of educational tradition in this village will be wiped out." Olbertz continued, "There are a number of other schools in the vicinity of Strobeck," emphasizing the economical savings realized through consolidation of resources. However, there's more at stake here besides Eurodollars. "Chess is not only taught in the classroom but played with enthusiasm by pupils in the playground and in after-school clubs." Ms. Heizmann pleaded: "The education ministry says that a minimum of 40 students must enrol in the school each year. But this year we just don't have enough children. More about the protest The current Mayor of Schachdorf Ströbeck is Rudi Krosch. Letters and emails of protest can be directed to: Minister for Culture of Sachsen-Anhalt A montage of Schachdorf Ströbeck.....      and, of course, the chessboard winners...  |