|

|

~ the "Morphy - Deacon" games

The Deacon controversy provided a diversion that kept Morphy's name in

the limelight even though he wasn't playing any public chess. It's a bit

complicated and convoluted, but basically insignificant since it was

doomed from it's inception. Both Lawson and Sergeant devote a chapter to

this affair showing why it was doomed to failure.

Frederich Deacon, commonly called Frederic or Frederick, was a strong

Belgian amateur living in London. Some of his matches indicate his

relative strength:

1851 Deacon-Löwe +7-2=1

1852 Deacon-Mayet +5-2

1863 Steinitz-Deacon +5-1=1

|

December17, 1859 an article in the Illustrated London News advertising

Staunton's soon-to-be released Guide to Chess, published

two games, a King's Gambit and an Evan's Gambit contested by Frederick Deacon and Paul Morphy, each

contestant winning one.

"...immediately upon seeing these games, Morphy pronounced them forgeries,

asserting he had never played at all with Deacon. He also stated that one of the

games was shown to him in London by the French player, de Riviere, as having

been won by him [Riviere] from the Englishman [Deacon] and in this Mr. Morphy

was corroborated by M. de Riviere before his statement reached Europe." -

Forney's War Press, Philadelphia, 1864

Morphy wrote to W. J. A. Fuller on January 19, 1860

Dear Mr. Fuller,

The two games published by Staunton in the Illustrated London News of

December 17th were not played with myself and Deacon. I never contested a

single game with Deacon, either on even terms or at odds. Had I played at

all, I would have given him the Pawn and Move at least, as public estimation

does not rank him as a player equal to Owen, to whom I yielded those odds

successfully. One of the games published in the Illustrated London News -

the Evan's Gambit - was shown to in London by Riviere as having been

played between Deacon and himself. I do not know who Deacon's competitor was

in the other game but must repeat that someone has been guilty of deliberate

falsehoods in both instances.

Ever yours,

Paul Morphy

New Orleans Delta, January 22, 1860

The games published in the Illustrated London News of the 17th

December last and purporting to have been played between Messrs. Morphy and

Deacon; were certainly never played by the former gentleman, indeed, he

never played a game with Deacon. If we did not know who the chess editor of

in the Illustrated News is, we might suppose that here he committed

an error, but being aware that the Chess Department of that paper is under

the care of Howard Staunton, we do not hesitate to say that he willfully

attributed games of inferior quality to Mr. Morphy, well knowing they had

never been played by him. This is in perfect accordance with his course

heretofore, but it's needless to say that no one will be gulled by this new

dodge of Mr. Staunton, as it will be duly exposed, we hope, by all chess

publishing papers.

Chess Monthly, March, 1860

We are obliged to state that the games in question are forgeries, and

that Mr. Morphy never played any games whatsoever with Mr. Deacon. Had he

contended with the gentleman, he would have given him Pawn and move at least

as public opinion does not rank him as a player as high as Mr. Owen to whom

Mr. Morphy successfully yielded these odds.

Deacon's letter:

May 9, 1860. 3 Hales Place

South Lambeth

Dear Sir:

In answer to your letter of yesterday, I need hardly say how happy

and thankful I am to give the particulars of my playing with Mr. Morphy; to

bear out gentlemen who have so fairly, and to their honor, preferred

believing in the fallibility of memory, rather than in loathsome — may I not

say impossible — crime.

On the night when Mr. Morphy played his blindfold game at the

London Chess Club, Mr. Lowenthal and myself accompanied Mr. Morphy and his

brother-in-law from the Club, as far as Charing Cross; on leaving them, both

Mr. Morphy and his brother-in-law pressed me to call upon them at the

"British Hotel." This invitation was repeated a day or two afterwards at the

St. James Chess Club, and on the following Monday I called upon them at that

hotel. I was accompanied by my cousin, Col. Charles Deacon, and Mr. Morphy

received us very courteously, and showed us a game he had played at Paris,

and then played two games with me, the first of which he won, and lost the

second.

One of the waiters came in the room several times, and my cousin

was present while Mr. Morphy played with me. Our visit was made at about

half-past ten in the morning, and we left at about two o'clock. On the

evening of that day, I took down the games, together with some others,

although I only put Mr. Morphy's name to the game I had won of him, and that

game my cousin distinctly remembers, with some remarks which were made

during and after the play'. These games were played exactly as they were

published in the London Illustrated News.

Col. Deacon is now in Westmoreland, but I will write to him, by

to-day's post, and he will give you his corroboration of these

circumstances.

Believe me, sincerely yours,

Fred. Deacon

A war of words broke out. Staunton, who published the games, at worst

knowing they were forgeries or at least accepting them without question,

whereas they should have raised a red flag, brought the power of his pen to

bear against Morphy who was taking no part in this affair beyond his original

denial of having ever played Deacon.

Illustrated London News, March 31, 1860:

The games were published, accompanied by annotations from the pen of the

English player, Mr. Deacon, in our paper of December 17, 1859. Upon their

reaching America, Mr. Morphy flatly denied that he had ever played a single

game with Mr. Deacon. This denial might be pardoned if expressed in

gentlemanly terms on the ground that the American had forgotten, among

battles with so many eminent opponents an encounter with one so little

known. But Mr. Morphy, not content with denying never having played with Mr.

Deacon, condescends to deprecate his skills and asserts, in the most

offensive manner, that "someone had been guilty of deliberate falsehood..."

Now apart from the incredible stupidity and grossness of such a charge, what

is most remarkable in the affair (giving Morphy credit for really having

forgotten his play with Mr. Deacon) is the surpassing vanity of that

gentleman... if there has been any deliberate falsehood in the matter, it

originated on the other side of the Atlantic.

Morphy's credible witnesses, his brother-in-law John D. Sybrandt who was also

the Swedish and Norwegian Consul in New Orleans and Jules Arnous de Riviere,

one of the most respected editors and chess players in France along with

Morphy's own reputation of integrity as well as for his famed memory

completely overwhelmed both Staunton's and Deacon's weak and ultimately

unsupported cases. Wilhelm Steinitz, much later, mentioned similar attempts by

Deacon for trying to falsify games between the two of them.

Sergeant subscribed to B. Goulding Brown's theory that the Morphy-Deacon

games actually took place and that Morphy's failure to recognize, or admit,

them as such, was an indication of the "first signs of that mental illness

which was to make a tragedy of his last years."

Even besides the nonsensical explanation for the games if they had been

actually played, Sergeant's de facto acceptance of Brown's

position is a mystery since Brown's writings on virtually anything having to

do with Morphy are seeped in adverse bias and misrepresentation,

while Sergeant's own writings indicate his belief that Morphy's mental illness

was minimal and only manifested late in his life.

...and the incident became an interesting, confusing but ultimately

unimportant footnote in chess history.

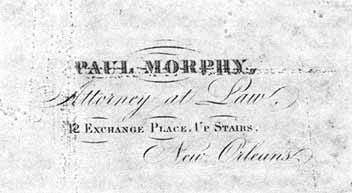

According

to Philip Sergeant, Morphy

had opened a law office at 12 Exchange Place and had cards printed up

(according to David Lawson, none of this happened until after Morphy returned

from Paris)

but after two months, he closed shop and took off for New York supposedly to

catch a ship to Paris where his mother and his sister, Helena, had already

gone to visit his other sister, Malvina who had moved there permanently. But

it would be some time before Paul would leave for Europe. He arrived in

New York no later than June and stayed through October. During that time his

contract with the Ledger ran out and Ledger owner, Robert Bonner, finding that

chess was not as popular as he had hoped, especially with Morphy not playing

anymore, chose not to renew the contract which was extravagant by any measure. According

to Philip Sergeant, Morphy

had opened a law office at 12 Exchange Place and had cards printed up

(according to David Lawson, none of this happened until after Morphy returned

from Paris)

but after two months, he closed shop and took off for New York supposedly to

catch a ship to Paris where his mother and his sister, Helena, had already

gone to visit his other sister, Malvina who had moved there permanently. But

it would be some time before Paul would leave for Europe. He arrived in

New York no later than June and stayed through October. During that time his

contract with the Ledger ran out and Ledger owner, Robert Bonner, finding that

chess was not as popular as he had hoped, especially with Morphy not playing

anymore, chose not to renew the contract which was extravagant by any measure.

Morphy was staying at the Fifth Avenue Hotel and he visited the New York Chess

Club fairly regularly but only played perhaps a dozen games either at Knight

or Rook odds. Louis Paulsen, who was also in New York, tried in vain to secure

a match with Morphy at even terms - which Morphy wouldn't even consider. When

he counter offered to play Paulsen at Pawn and Move odds, Paulsen hesitated,

uncertain whether this was more advantageous to odds-giver than to the

odds-receiver. Morphy meanwhile, not wanting to play at all, wrote that he was

getting "heartily tired of the subject" of arranging a match Paulsen.

Just as Morphy's appearance stirred up excitement about chess in America,

his sudden retirement caused a noticeable void:

A July 1861 article from a New York newspaper stated:

The Chess-mania which seized upon the whole nation when Morphy's brilliant

star first rose on the horizon, was violent and exaggerated; and as his star

rushed up into the zenith of its world-wide renown, and then with equal

rapidity withdrew itself from the public gaze in the obscurity of private life

from which there seems small prospect of re-appearance, the fever died away

with it, and it's not to be wondered at that Chess Clubs and Chess Columns,

that owed their existence to the excitement of the day, should dwindle away

and disappear.

Then on

November 6, 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected president of the United States

and within weeks Southern states were discussing secession. On December 20,

1860, South Carolina left the Union followed by Mississippi on January 9,

Florida on January 10, Alabama on January 11, Georgia on January 19 and

Louisiana on January 26.

Signing the Ordinance of Secession of Louisiana, January 26, 1861

by Enoch Wood Perry Jr. (1831-1915)

1861 Oil on canvas

Any plans Morphy might have had to settle into a quiet, leisurely

professional career as an attorney were completely disturbed on April

12, 1861 when General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, the Great Creole,

commanded the artillery attack on Fort Sumter.

Paul held strong anti-secessionist views, but at the same time, the

Morphy's owned slaves and were distinctly Southern aristocrats whose way of

life was threatened by Northern conquest. Many Southerners, even those

predisposed to being against secession, viewed the Civil War more as a war of

aggression in which they had no choice but to support their state and

therefore, the Confederacy. In any case, it seems at the onset of the war,

Paul Morphy did visit Richmond, which had been established as the

Confederate capitol on May 21, 1861, and he met with Pierre Beauregard

with whom he was undoubtedly already acquainted, possibly hoping to

serve as a non-combatant or in some diplomatic capacity. His brother, Edward, had already joined the

Louisiana Tigers - the Seventh Regiment of New Orleans - which recruited from

the finest families in New Orleans. While it's known for certain that Morphy

went to Richmond in October 1861, many of the details of the trip are a

mystery.

The October 24 issue of the Richmond Dispatch conclusively places

Morphy in Richmond:

RICHMOND CHESS CLUB -- A meeting of the members of the Club will be held in

their rooms over the J. P. Duval Drug Store, THIS EVENING (Thursday,)

24th inst., at 8 o'clock.

Mr. Morphy has kindly consented to be present.

and in the same issue

Paul Morphy -- This distinguished gentleman has been in our city for some

days and has received visits and attentions from a number of our citizens to

whom his unassuming dignity and agreeable manners has made his society very

pleasant. He is a fine specimen of Southern gentleman. From a notice in

another column, it appears he is expected to visit the rooms of the Richmond

Chess Club this evening.

Mrs. Burton Harrison of Richmond mentions Morphy in her memoirs,

Recollections Grave and Gay:

Early in the war Paul Morphy, the celebrated chess player, whom we knew in

Richmond, accepted a commission to purchase for me in New Orleans, whither he

was returning, a French voilette of real black thread lace, the height

of my ambition. When the veil arrived, as selected by himself, we voted

Mr. Morphy an expert in other arts than chess.

Morphy did visit the Richmond Chess Club that evening and played at least

ten games at Knight odds, winning eight.

According to Gilbert R. Frith of Staunton, Virginia, and president of the

State Chess Association of Virginia as related in the Columbia Chess

Chronicle August 18, 1888 and January 24, 1889, Paul Morphy had an

intriguing encounter involving a painting, entitled, The Chess Players

by Moritz August Retzsch (most likely a copy of the painting shown below).

"The arrival of the noted player excited, even at that troublous time, a

keen interest among the lovers of the kingly game. An invitation was extended

to the cha mpion,

and, with himself as the center, a coterie of notables assembled for an

evening's play at the home of Mr. H. (Reverend R. R. Howison) ...

While at supper Morphy's attention was attracted by a picture which hung

prominently upon the wall, Mephistopheles playing a game of Chess with a young

man for his soul. The Chessmen with which his Satanic Majesty plays are the

Vices; the pieces of the young man are, or have been, the Virtues -- for alas!

he has very few left. In bad case, indeed, is the unhappy youth, for his game,

as represented, appears not only desperate, but hopeless, and his fate sealed.

His adversary gloats in anticipation of the final coup, and the

gleaming smile on the face of the latter intensifies the despair which that of

the young man shows. mpion,

and, with himself as the center, a coterie of notables assembled for an

evening's play at the home of Mr. H. (Reverend R. R. Howison) ...

While at supper Morphy's attention was attracted by a picture which hung

prominently upon the wall, Mephistopheles playing a game of Chess with a young

man for his soul. The Chessmen with which his Satanic Majesty plays are the

Vices; the pieces of the young man are, or have been, the Virtues -- for alas!

he has very few left. In bad case, indeed, is the unhappy youth, for his game,

as represented, appears not only desperate, but hopeless, and his fate sealed.

His adversary gloats in anticipation of the final coup, and the

gleaming smile on the face of the latter intensifies the despair which that of

the young man shows.

With the close of the supper, deeply interested, Morphy

approached the picture, studied it awhile intently, then turning to his host

he said modestly: 'I think I can take the young man's game and win.' 'Why,

impossible!' was the answer, 'Not even you, Mr. Morphy, can retrieve that

game.' 'Yet I think I can,' said Morphy. 'Suppose we place the men and

try.' A board was arranged, and the rest of the company gathered round it,

deeply interested in the result. To the surprise of everyone, victory was

snatched from the devil and the young man saved."

In 1994

John T. Campbell claimed to have unearthed the actual picture, a

lithograph, owned by the Reverend Howison and promised to donated

enlarged photographs of the picture to the U. S. Hall of Fame, a promise

seemingly unfulfilled.

He wrote in the November/December 1994 edition of the Virginia Chess

Newsletter:

The version of the tale accepted within the Howison family differs slightly

from the popular legend. Rather than "defending the young man's position,"

Morphy is said to have played several games from a position based upon the

lithograph as a form of handicapping. That is, as a change of pace from his

usual custom of conceding rook, queen or other material odds versus amateur

opponents, Morphy simply concocted a starting position resembling that in the

picture. Then his fellow dinner guests took turns trying out the Black

(superior) side against the champion. There is no indication how Morphy

performed win/loss-wise against this handicap.

Through the years, scholars have offered differing interpretations of the

chess position in the Retzsch original. It's no easy task because the pieces

are stylized and not readily equated to regular chess pieces, plus the view

angle makes it hard to be certain which squares they occupy. The discovery of

the 'authenticated' Morphy lithograph could rekindle speculation, although the

issue loses much of its significance if we accept the Howison family version

of the tale, there being no claim that Morphy defended a position directly

from the picture. In any case, the now-established fact that Howison family

descendants possess such a lithograph argues that the "Devil and Paul Morphy"

legend has its basis in truth.

Gilbert R. Frith also states that Morphy was "an officer on Beauregard's

staff." How much credence can be put in that is questionable. Frances

Parkinson Keyes in her historical novel, The Chess Players, portrayed

Morphy as being rejected by Beauregard when seeking the position as his

aide-de-camp and then recruited as a spy by Judah Benjamin whose wife was

related to the Morphys, and finally working directly under John Slidell (who

was also married to a Creole) in France. Lawson claims there's nothing for

Keyes to base this on and since Morphy waited a year between visiting Richmond

and going to Paris and then returned a year before the war ended, the entire

spy story doesn't even make sense.

In Reminiscences of Paul Morphy By George Haven Putnam (Adt. and Bvt.-Major,

176th regt. N.Y.S. vols.) a different view of Morphy, living in New Orleans before

leaving for France, is shown:

In 1857, a convention was held in New York of the

International Chess Association, or of players representing the Associations

of the States. I was at the time but a youngster, but I had interested myself

in chess and I secured the opportunity of visiting from time to time the rooms

of the New York Chess Club where the tournament was being held.

There came to the convention with the proper

introductions from the chess authorities in Louisiana a good looking young

lawyer named Paul Morphy. This name had not before been known among the chess

players of the country, but the youngster made clear with his first game that

he was a master of the art. He fought his way through, defeating one opponent

after the other, until he came out at the close of the tournament victor and

with an exceptional number of won games to his credit.

One of his sturdiest opponents was another youngster

whose name had not previously come up in chess circles, Paulsen, who came from

Wisconsin and whose heritage was Swedish.

It is my memory that in this tournament, Paulsen came out second to Morphy. I

recall also that he made a new precedent in the playing of games out of sight

of the board. I think that he carried on at one time no less than twelve such

games with a large majority of wins

The table on which Morphy won his successes in the New

York Chess Club was given by the club to its President, John Treat Irving.

Later it was given by Mr. Irving, with a silver plate recording its use by

Morphy, to the Century Club, where it now rests.

One or two volumes were promptly brought into print

giving the report of the Morphy games, and one of these I carried in my

haversack through the years of the war.

My regiment happened to be among those that took part

in 1862 in the occupation of Louisiana, and I had occasion during two years of

the campaigns in Louisiana to be in and out of New Orleans. A friend in one of

the New England regiments, also a chess player, pointed out to me one day

crossing Carondelet Street the figure of Morphy. This must have been in 1863.

Morphy was walking with the lagging step of an ill man.

He did not die until some years after the close of the war, but I was told

that at the time I saw him he was already an invalid. I think his death

finally came from softening of the brain. The doctors had forbidden chess and

he seems to have had very few other interests or amusements.

There was also, however, upon him a special pressure of

trouble. While a loyal citizen of Louisiana, he was opposed to secession. He

did not believe that the Republic ought to be broken up. The men of the good

families in New Orleans, a group to which young Morphy certainly belonged,

were nearly all members of the "Louisiana Tigers," the Seventh Regiment of New

Orleans.

Morphy had refused to join with these old-time

associates in the attempt to overthrow the Republic. This brought him into

social isolation. The girls were said to have scoffed at him. He ought, of

course, to have done what other Southerners, objecting to secession, did. He

should have made a home for himself in Paris, or somewhere in England. He

remained, however, in New Orleans, boycotted and ill, and the last years of

his life brought to him nothing but sadness.

New York, January 19, 1923

One problem with Mr. Putnam's recollection above with the statement:

"This must have been in 1863."

Putnam was born in 1844. His father was George Palmer Putnam, founder of G.

P. Putnam Son's Publishing House, where George Haven eventually ran. At

the time he saw Morphy, Putnam was only 18 or 19.

Although Morphy was in New Orleans during its capture in April 1862 and its

occupation under Butler beginning in May, on October 10 1862 Morphy packed his

valuables and gained incognito passage, accompanied by his friend, Charles

Maurian on the Cuba-bound Spanish steamboat, Blasco de Garay, with the

ultimate destination of Paris. Besides the insufferable idea of living under

Yankee, particularly Butler's, rule and of being required to take the oath of

allegiance to the Union or face exile and confiscation of property, Morphy had

other possible reasons for leaving New Orleans. Paul's mother and his sister,

Helena, had already moved to Paris; his anti-secessionist views as well has

his non-participation in the war probably made him unpopular in his own city;

the Confederacy had passed its first Conscription Act in April of 1862, making

Paul potentially liable to be drafted (although New Orleans was in Union

hands, putting residents out of reach for conscription).

Benjamin

"Beast" Butler by Matthew Brady

|